Other Subject

anatomy

physiology

science

digestive

system

BODY SYSTEM

BODY

nerve supply

Peritoneal Folds

mouth

pharynx

esophagus

Digestive System Processes and Regulation

Anatomy of a Tooth

Cardiovascular

Endocrine

Integumentary

Lymphatic

Muscular

Nervous

Respiratory

Skeletal

Urinary

Lamina propria

Epithelium

Muscularis mucosa

Nerve Supply

myenteric plexus

submucosal plexus

Greater omentum

Falciform ligament

Lesser omentum

Mesentery

Mesocolon

University/Undergrad

Chapter 23: The Digestive System

Overview of the Digestive System

Contribution of Other Body Systems to the Digestive System

Body system | Benefits received by the digestive system |

|---|---|

Cardiovascular | Blood supplies digestive organs with oxygen and processed nutrients |

Endocrine | Endocrine hormones help regulate secretion in digestive glands and accessory organs |

Integumentary | Skin helps protect digestive organs and synthesizes vitamin D for calcium absorption |

Lymphatic | Mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue and other lymphatic tissue defend against entry ofpathogens; lacteals absorb lipids; and lymphatic vessels transport lipids to bloodstream |

Muscular | Skeletal muscles support and protect abdominal organs |

Nervous | Sensory and motor neurons help regulate secretions and muscle contractions in the digestive tract |

Respiratory | Respiratory organs provide oxygen and remove carbon dioxide |

Skeletal | Bones help protect and support digestive organs |

Urinary | Kidneys convert vitamin D into its active form, allowing calcium absorption in the small intestine |

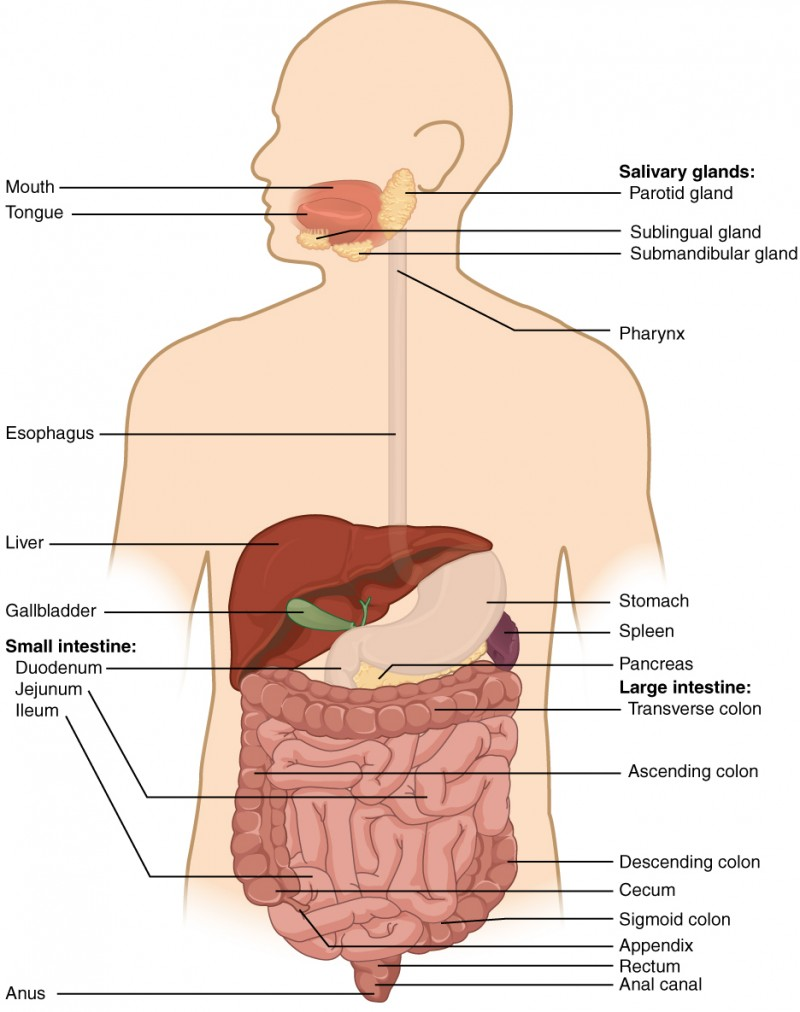

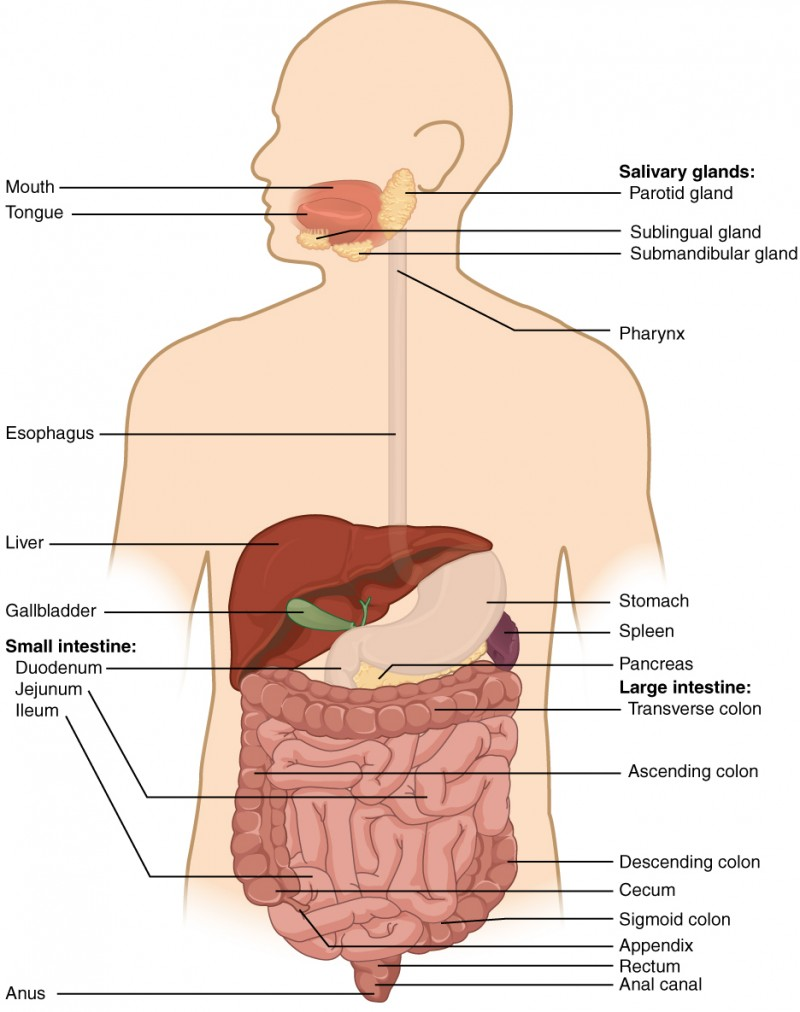

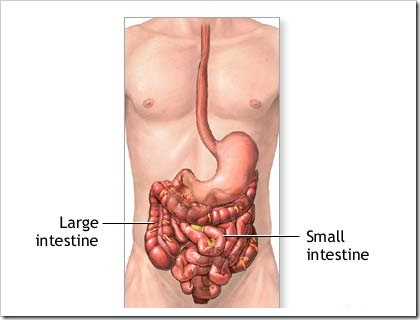

Also called the gastrointestinal (GI) tract or gut, the alimentary canal (aliment- = “to nourish”) is a one-way tube about 7.62 meters (25 feet) in length during life and closer to 10.67 meters (35 feet) in length when measured after death, once smooth muscle tone is lost.

Each accessory digestive organ aids in the breakdown of food.

The mucosa is referred to as a mucous membrane, because mucus production is a characteristic feature of gut epithelium.

Epithelium - In the mouth, pharynx, esophagus, and anal canal, the epithelium is primarily a non-keratinized, stratified squamous epithelium.

Lamina propria - In addition to loose connective tissue, the lamina propria contains numerous blood and lymphatic vessels that transport nutrients absorbed through the alimentary canal to other parts of the body.

Muscularis mucosa - This thin layer of smooth muscle is in a constant state of tension, pulling the mucosa of the stomach and small intestine into undulating folds.

The third layer of the alimentary canal is the muscularis (also called the muscularis externa).

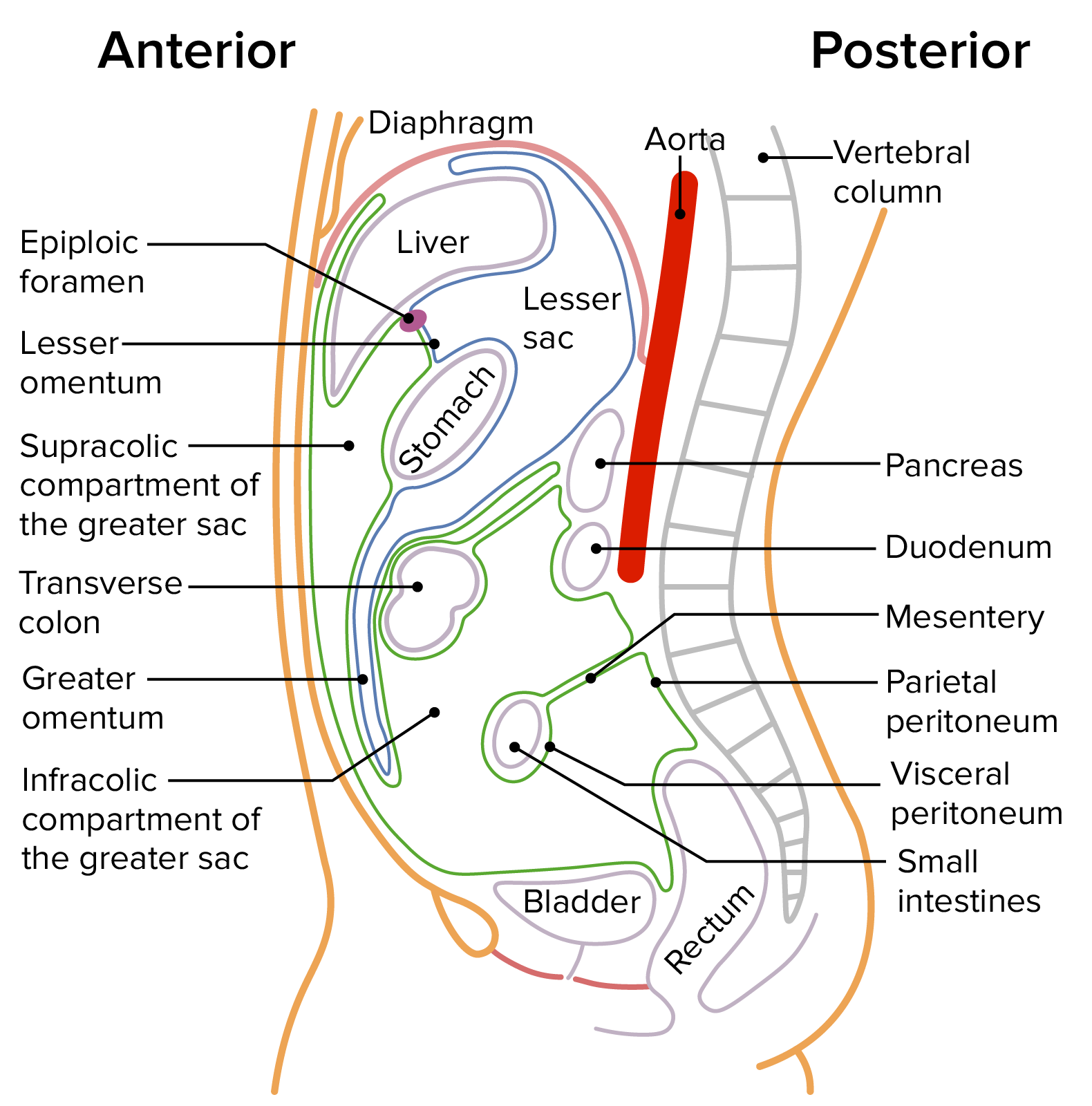

The serosa is the portion of the alimentary canal superficial to the muscularis.

Nerve Supply

The myenteric plexus (plexus of Auerbach) lies in the muscularis layer of the alimentary canal and is responsible for motility, especially the rhythm and force of the contractions of the muscularis.

The submucosal plexus (plexus of Meissner) lies in the submucosal layer and is responsible for regulating digestive secretions and reacting to the presence of food.

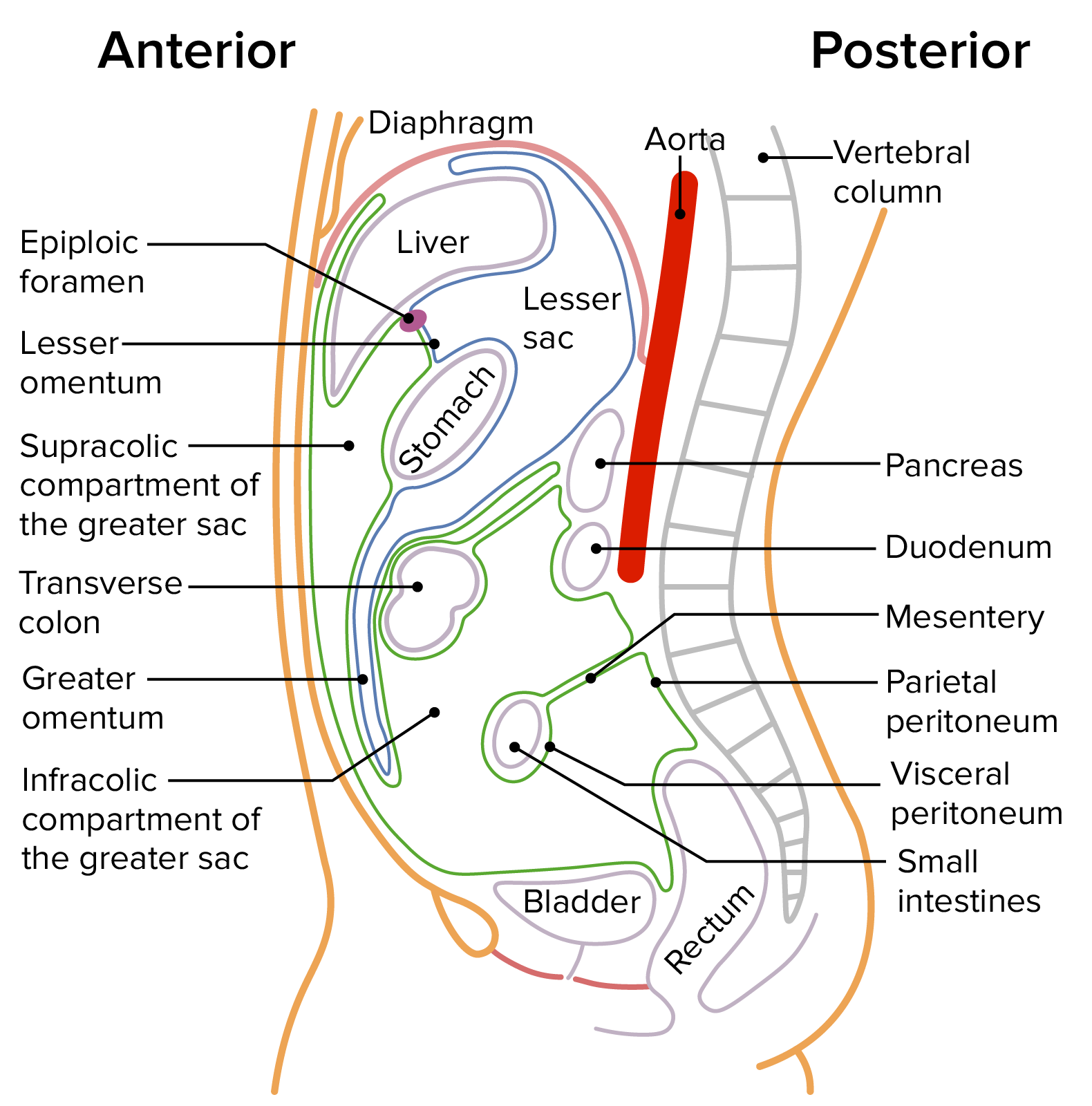

The Five Major Peritoneal Folds

Fold | Description |

|---|---|

Greater omentum | Apron-like structure that lies superficial to the small intestine and transverse colon; a site of fat deposition in people who are overweight |

Falciform ligament | Anchors the liver to the anterior abdominal wall and inferior border of the diaphragm |

Lesser omentum | Suspends the stomach from the inferior border of the liver; provides a pathway for structures connecting to the liver |

Mesentery | Vertical band of tissue anterior to the lumbar vertebrae and anchoring all of the small intestine except the initial portion (the duodenum) |

Mesocolon | Attaches two portions of the large intestine (the transverse and sigmoid colon) to the posterior abdominal wall |

Digestive System Processes and Regulation

The first of these processes, ingestion, refers to the entry of food into the alimentary canal through the mouth.

Propulsion, which refers to the movement of food through the digestive tract. It includes both the voluntary process of swallowing and the involuntary process of peristalsis.

Peristalsis consists of sequential, alternating waves of contraction and relaxation of alimentary wall smooth muscles, which act to propel food along.

Mechanical digestion is a purely physical process that does not change the chemical nature of the food. Instead, it makes the food smaller to increase both surface area and mobility.

Segmentation, which occurs mainly in the small intestine, consists of localized contractions of circular muscle of the muscularis layer of the alimentary canal.

In chemical digestion, starting in the mouth, digestive secretions break down complex food molecules into their chemical building blocks (for example, proteins into separate amino acids).

In defecation, the final step in digestion, undigested materials are removed from the body as feces.

The Mouth, Pharynx, and Esophagus

The cheeks, tongue, and palate frame the mouth, which is also called the oral cavity (or buccal cavity).

At the entrance to the mouth are the lips, or labia (singular = labium).

The labial frenulum is a midline fold of mucous membrane that attaches the inner surface of each lip to the gum.

The pocket-like part of the mouth that is framed on the inside by the gums and teeth, and on the outside by the cheeks and lips is called the oral vestibule.

Moving farther into the mouth, the opening between the oral cavity and throat (oropharynx) is called the fauces (like the kitchen "faucet").

Perhaps you have heard it said that the tongue is the strongest muscle in the body.

Many small salivary glands are housed within the mucous membranes of the mouth and tongue.

The Major Salivary Glands

The submandibular glands, which are in the floor of the mouth, secrete saliva into the mouth through the submandibular ducts.

The sublingual glands, which lie below the tongue, use the lesser sublingual ducts to secrete saliva into the oral cavity.

The parotid glands lie between the skin and the masseter muscle, near the ears.

Saliva is essentially (95.5 percent) water.

Perhaps the most important ingredient in salvia from the perspective of digestion is the enzyme salivary amylase, which initiates the breakdown of carbohydrates.

The autonomic nervous system regulates salivation (the secretion of saliva).

The Teeth

The teeth, or dentes (singular = dens), are organs similar to bones that you use to tear, grind, and otherwise mechanically break down food.

The eight incisors, four top and four bottom, are the sharp front teeth you use for biting into food.

The four cuspids (or canines) flank the incisors and have a pointed edge (cusp) to tear up food.

Posterior to the cuspids are the eight premolars (or bicuspids), which have an overall flatter shape with two rounded cusps useful for mashing foods.

The most posterior and largest are the 12 molars, which have several pointed cusps used to crush food so it is ready for swallowing.

Anatomy of a Tooth

Gingivae (commonly called the gums) are soft tissues that line the alveolar processes and surround the necks of the teeth.

The two main parts of a tooth are the crown, which is the portion projecting above the gum line, and the root, which is embedded within the maxilla and mandible.

Surrounding the pulp cavity is dentin, a bone-like tissue. In the root of each tooth, the dentin is covered by an even harder bone-like layer called cementum.

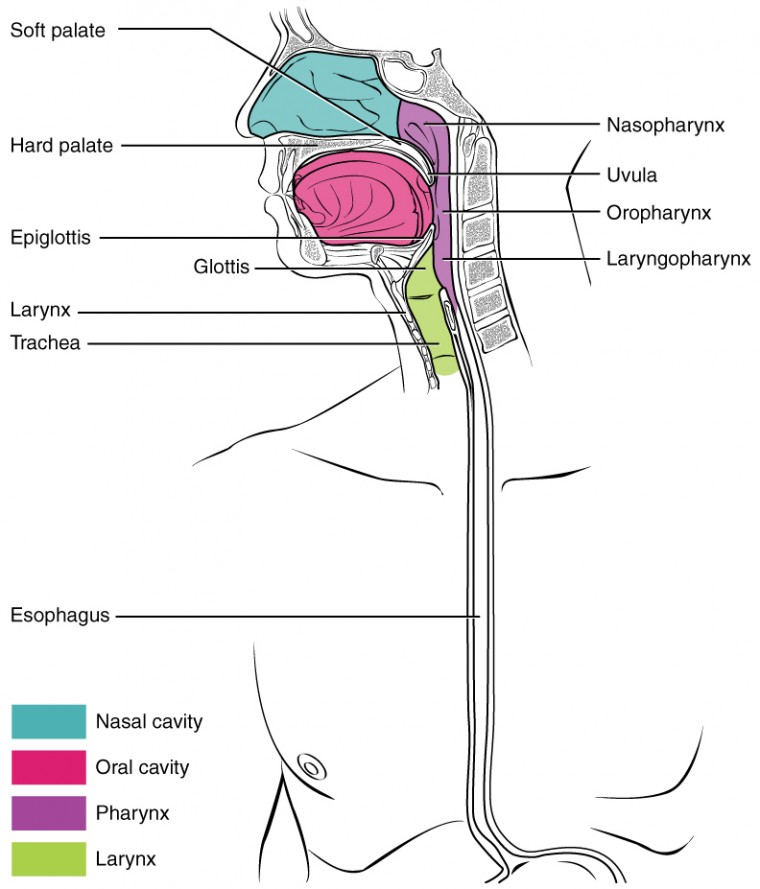

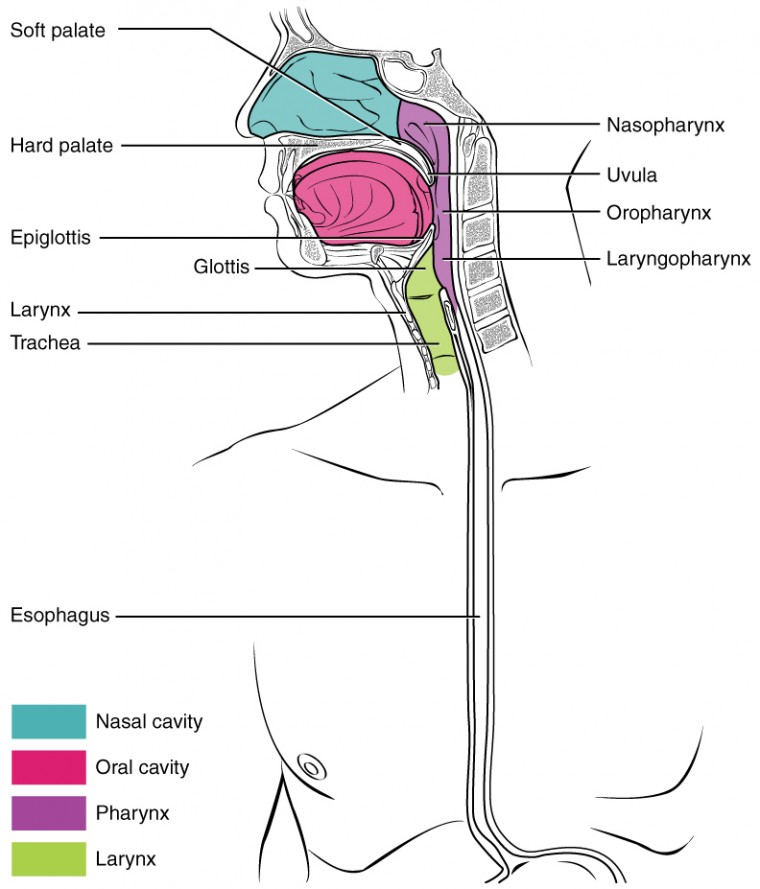

The Pharynx

The pharynx (throat) is involved in both digestion and respiration.

The other two subdivisions, the oropharynx and the laryngopharynx, are used for both breathing and digestion.

The Esophagus

The esophagus is a muscular tube that connects the pharynx to the stomach.

The upper esophageal sphincter, which is continuous with the inferior pharyngeal constrictor, controls the movement of food from the pharynx into the esophagus.

Food passes from the esophagus into the stomach at the lower esophageal sphincter (also called the gastroesophageal or cardiac sphincter).

Deglutition: Deglutition is another word for swallowing—the movement of food from the mouth to the stomach.

The Voluntary Phase: The voluntary phase of deglutition (also known as the oral or buccal phase) is so called because you can control when you swallow food.

The Stomach

There are four main regions in the stomach: the cardia, fundus, body, and pylorus.

The cardia (or cardiac region) is the point where the esophagus connects to the stomach and through which food passes into the stomach.

The narrower end is called the pyloric canal, which connects to the duodenum.

In the absence of food, the stomach deflates inward, and its mucosa and submucosa fall into a large fold called a ruga.

Cells that make up the pyloric antrum secrete mucus and a number of hormones, including the majority of the stimulatory hormone, gastrin.

Located primarily in the middle region of the gastric glands are parietal cells, which are among the most highly differentiated of the body’s epithelial cells.

Located primarily in the basal regions of gastric glands are chief cells, which secrete pepsinogen, the inactive proenzyme form of pepsin.

Enteroendocrine cells found in the gastric glands secrete various hormones into the interstitial fluid of the lamina propria.

Gastric Secretion

The cephalic phase (reflex phase) of gastric secretion, which is relatively brief, takes place before food enters the stomach.

The gastric phase of secretion lasts 3 to 4 hours, and is set in motion by local neural and hormonal mechanisms triggered by the entry of food into the stomach.

The intestinal phase of gastric secretion has both excitatory and inhibitory elements.

The Mucosal Barrier

The stomach is protected from self-digestion by the mucosal barrier.

The mucosa of the stomach is exposed to the highly corrosive acidity of gastric juice.

Mechanical Digestion

A mixing wave is a unique type of peristalsis that mixes and softens the food with gastric juices to create chyme.

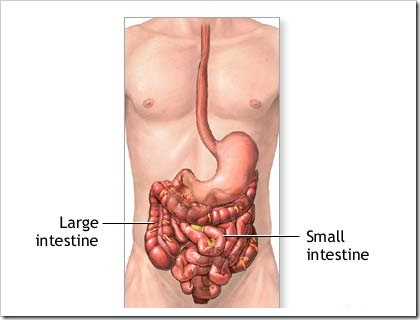

The Small and Large Intestines

Chyme released from the stomach enters the small intestine, which is the primary digestive organ in the body.

Also called a plica circulare, a circular fold is a deep ridge in the mucosa and submucosa.

Within the circular folds are small (0.5–1 mm long) hairlike vascularized projections called villi (singular = villus) that give the mucosa a furry texture.

As their name suggests, microvilli (singular = microvillus) are much smaller (1 μm) than villi.

The mucosa between the villi is dotted with deep crevices that each lead into a tubular intestinal gland (crypt of Lieberkühn), which is formed by cells that line the crevices.

The Large Intestine: The large intestine is the terminal part of the alimentary canal.

Subdivisions: The large intestine is subdivided into four main regions: the cecum, the colon, the rectum, and the anus.

Cecum

The first part of the large intestine is the cecum, a sac-like structure that is suspended inferior to the ileocecal valve.

The appendix (or vermiform appendix) is a winding tube that attaches to the cecum.

The mesoappendix, the mesentery of the appendix, tethers it to the mesentery of the ileum.

Colon

The cecum blends seamlessly with the colon.

At the inferior surface of the liver, the colon bends to form the right colic flexure (hepatic

flexure) and becomes the transverse colon.

After entering the pelvis inferiorly, it becomes the s-shaped sigmoid colon, which extends medially to the midline.

Rectum: Food residue leaving the sigmoid colon enters the rectum in the pelvis, near the third sacral vertebra.

Anal Canal: Food residue reaches the last part of the large intestine, the anal canal, which is located in the perineum, completely outside of the abdominopelvic cavity.

Anatomy

The teniae coli are three bands of smooth muscle that make up the longitudinal muscle layer of the muscularis of the large intestine, except at its terminal end.

The anal canal’s mucous membrane is organized into longitudinal folds, each called an anal column, which house a grid of arteries and veins.

Depressions between the anal columns, each called an anal sinus, secrete mucus that facilitates defecation.

The pectinate line (or dentate line) is a horizontal, jagged band that runs circumferentially just below the level of the anal sinuses, and represents the junction between the hindgut and external skin.

Mechanical Digestion

The presence of food residues in the colon stimulates a slow-moving haustral contraction.

Distension in the stomach and the breakdown products of digestion in the small intestine provoke the gastrocolic reflex, which increases motility, including mass movements, in the colon.

Accessory Organs in Digestion: The Liver, Pancreas, and Gallbladder

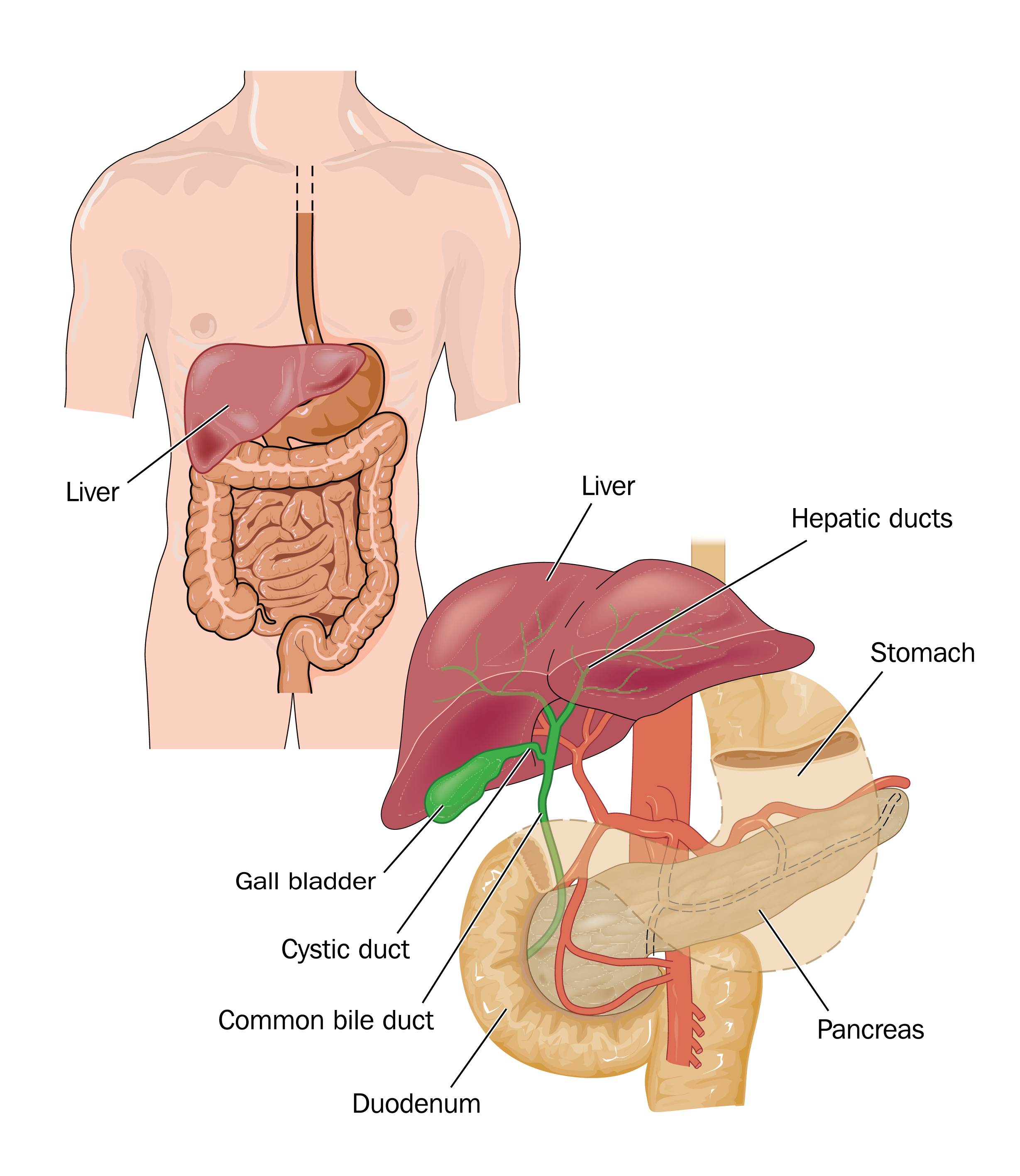

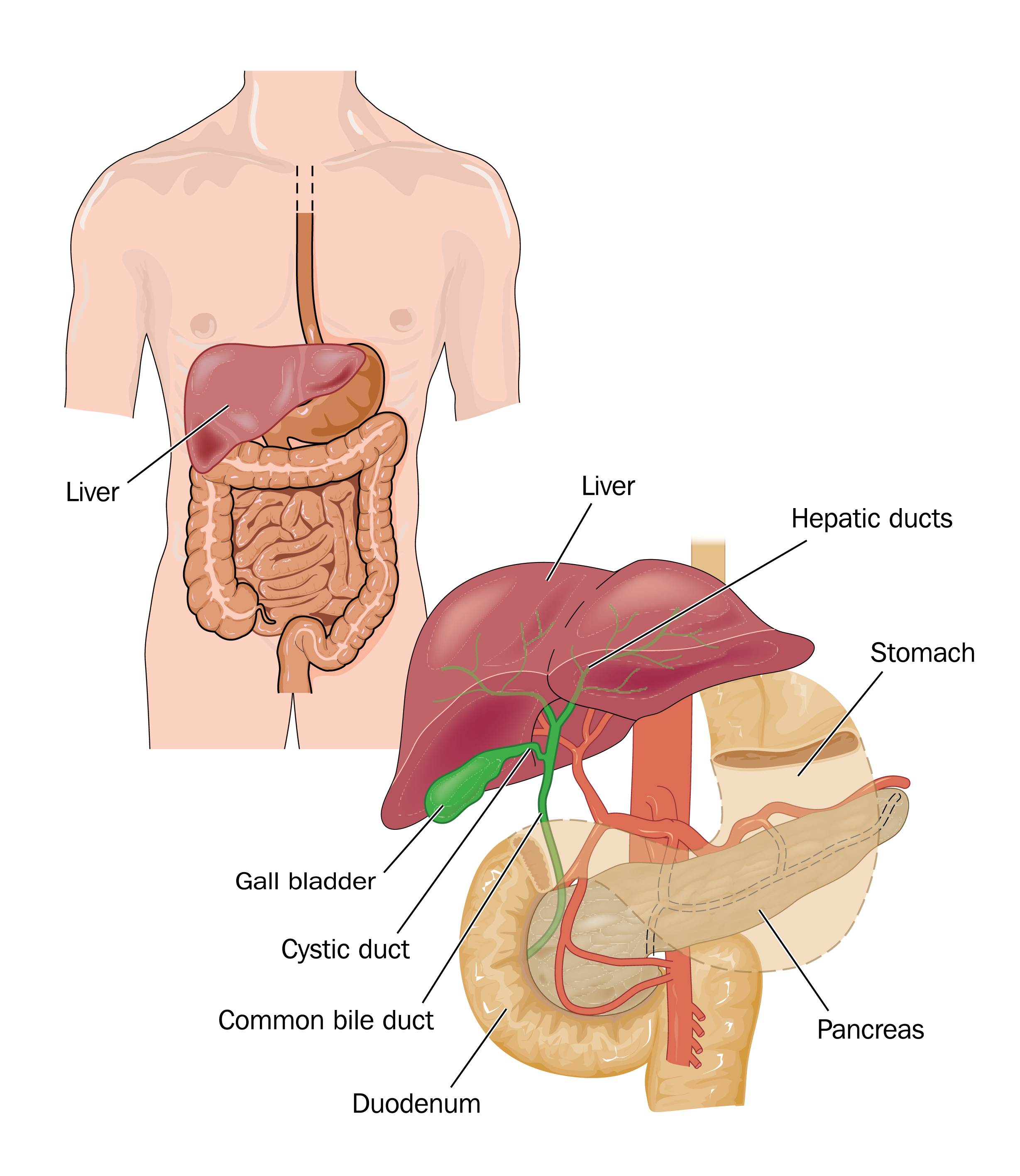

The liver is the largest gland in the body, weighing about three pounds in an adult.

The porta hepatis (“gate to the liver”) is where the hepatic artery and hepatic portal vein enter the liver.

A hepatocyte is the liver’s main cell type, accounting for around 80 percent of the liver's volume.

Plates of hepatocytes called hepatic laminae radiate outward from the portal vein in each hepatic lobule.

A hepatic sinusoid is an open, porous blood space formed by fenestrated capillaries from nutrient-rich hepatic portal veins and oxygen-rich hepatic arteries.

Bile is a mixture secreted by the liver to accomplish the emulsification of lipids in the small intestine.

Bilirubin, the main bile pigment, is a waste product produced when the spleen removes old or damaged red blood cells from the circulation.

The Pancreas

The soft, oblong, glandular pancreas lies transversely in the retroperitoneum behind the stomach.

The exocrine part of the pancreas arises as little grape-like cell clusters, each called an acinus (plural = acini), located at the terminal ends of pancreatic ducts.

The Gallbladder: The gallbladder is 8–10 cm (~3–4 in) long and is nested in a shallow area on the posterior aspect of the right lobe of the liver.

Chemical Digestion and Absorption: A Closer Look

The three lipases responsible for lipid digestion are lingual lipase, gastric lipase, and pancreatic lipase.

Two types of pancreatic nuclease are responsible for their digestion: deoxyribonuclease, which digests DNA, and ribonuclease, which digests RNA.

Chapter 23: The Digestive System

Overview of the Digestive System

Contribution of Other Body Systems to the Digestive System

Body system | Benefits received by the digestive system |

|---|---|

Cardiovascular | Blood supplies digestive organs with oxygen and processed nutrients |

Endocrine | Endocrine hormones help regulate secretion in digestive glands and accessory organs |

Integumentary | Skin helps protect digestive organs and synthesizes vitamin D for calcium absorption |

Lymphatic | Mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue and other lymphatic tissue defend against entry ofpathogens; lacteals absorb lipids; and lymphatic vessels transport lipids to bloodstream |

Muscular | Skeletal muscles support and protect abdominal organs |

Nervous | Sensory and motor neurons help regulate secretions and muscle contractions in the digestive tract |

Respiratory | Respiratory organs provide oxygen and remove carbon dioxide |

Skeletal | Bones help protect and support digestive organs |

Urinary | Kidneys convert vitamin D into its active form, allowing calcium absorption in the small intestine |

Also called the gastrointestinal (GI) tract or gut, the alimentary canal (aliment- = “to nourish”) is a one-way tube about 7.62 meters (25 feet) in length during life and closer to 10.67 meters (35 feet) in length when measured after death, once smooth muscle tone is lost.

Each accessory digestive organ aids in the breakdown of food.

The mucosa is referred to as a mucous membrane, because mucus production is a characteristic feature of gut epithelium.

Epithelium - In the mouth, pharynx, esophagus, and anal canal, the epithelium is primarily a non-keratinized, stratified squamous epithelium.

Lamina propria - In addition to loose connective tissue, the lamina propria contains numerous blood and lymphatic vessels that transport nutrients absorbed through the alimentary canal to other parts of the body.

Muscularis mucosa - This thin layer of smooth muscle is in a constant state of tension, pulling the mucosa of the stomach and small intestine into undulating folds.

The third layer of the alimentary canal is the muscularis (also called the muscularis externa).

The serosa is the portion of the alimentary canal superficial to the muscularis.

Nerve Supply

The myenteric plexus (plexus of Auerbach) lies in the muscularis layer of the alimentary canal and is responsible for motility, especially the rhythm and force of the contractions of the muscularis.

The submucosal plexus (plexus of Meissner) lies in the submucosal layer and is responsible for regulating digestive secretions and reacting to the presence of food.

The Five Major Peritoneal Folds

Fold | Description |

|---|---|

Greater omentum | Apron-like structure that lies superficial to the small intestine and transverse colon; a site of fat deposition in people who are overweight |

Falciform ligament | Anchors the liver to the anterior abdominal wall and inferior border of the diaphragm |

Lesser omentum | Suspends the stomach from the inferior border of the liver; provides a pathway for structures connecting to the liver |

Mesentery | Vertical band of tissue anterior to the lumbar vertebrae and anchoring all of the small intestine except the initial portion (the duodenum) |

Mesocolon | Attaches two portions of the large intestine (the transverse and sigmoid colon) to the posterior abdominal wall |

Digestive System Processes and Regulation

The first of these processes, ingestion, refers to the entry of food into the alimentary canal through the mouth.

Propulsion, which refers to the movement of food through the digestive tract. It includes both the voluntary process of swallowing and the involuntary process of peristalsis.

Peristalsis consists of sequential, alternating waves of contraction and relaxation of alimentary wall smooth muscles, which act to propel food along.

Mechanical digestion is a purely physical process that does not change the chemical nature of the food. Instead, it makes the food smaller to increase both surface area and mobility.

Segmentation, which occurs mainly in the small intestine, consists of localized contractions of circular muscle of the muscularis layer of the alimentary canal.

In chemical digestion, starting in the mouth, digestive secretions break down complex food molecules into their chemical building blocks (for example, proteins into separate amino acids).

In defecation, the final step in digestion, undigested materials are removed from the body as feces.

The Mouth, Pharynx, and Esophagus

The cheeks, tongue, and palate frame the mouth, which is also called the oral cavity (or buccal cavity).

At the entrance to the mouth are the lips, or labia (singular = labium).

The labial frenulum is a midline fold of mucous membrane that attaches the inner surface of each lip to the gum.

The pocket-like part of the mouth that is framed on the inside by the gums and teeth, and on the outside by the cheeks and lips is called the oral vestibule.

Moving farther into the mouth, the opening between the oral cavity and throat (oropharynx) is called the fauces (like the kitchen "faucet").

Perhaps you have heard it said that the tongue is the strongest muscle in the body.

Many small salivary glands are housed within the mucous membranes of the mouth and tongue.

The Major Salivary Glands

The submandibular glands, which are in the floor of the mouth, secrete saliva into the mouth through the submandibular ducts.

The sublingual glands, which lie below the tongue, use the lesser sublingual ducts to secrete saliva into the oral cavity.

The parotid glands lie between the skin and the masseter muscle, near the ears.

Saliva is essentially (95.5 percent) water.

Perhaps the most important ingredient in salvia from the perspective of digestion is the enzyme salivary amylase, which initiates the breakdown of carbohydrates.

The autonomic nervous system regulates salivation (the secretion of saliva).

The Teeth

The teeth, or dentes (singular = dens), are organs similar to bones that you use to tear, grind, and otherwise mechanically break down food.

The eight incisors, four top and four bottom, are the sharp front teeth you use for biting into food.

The four cuspids (or canines) flank the incisors and have a pointed edge (cusp) to tear up food.

Posterior to the cuspids are the eight premolars (or bicuspids), which have an overall flatter shape with two rounded cusps useful for mashing foods.

The most posterior and largest are the 12 molars, which have several pointed cusps used to crush food so it is ready for swallowing.

Anatomy of a Tooth

Gingivae (commonly called the gums) are soft tissues that line the alveolar processes and surround the necks of the teeth.

The two main parts of a tooth are the crown, which is the portion projecting above the gum line, and the root, which is embedded within the maxilla and mandible.

Surrounding the pulp cavity is dentin, a bone-like tissue. In the root of each tooth, the dentin is covered by an even harder bone-like layer called cementum.

The Pharynx

The pharynx (throat) is involved in both digestion and respiration.

The other two subdivisions, the oropharynx and the laryngopharynx, are used for both breathing and digestion.

The Esophagus

The esophagus is a muscular tube that connects the pharynx to the stomach.

The upper esophageal sphincter, which is continuous with the inferior pharyngeal constrictor, controls the movement of food from the pharynx into the esophagus.

Food passes from the esophagus into the stomach at the lower esophageal sphincter (also called the gastroesophageal or cardiac sphincter).

Deglutition: Deglutition is another word for swallowing—the movement of food from the mouth to the stomach.

The Voluntary Phase: The voluntary phase of deglutition (also known as the oral or buccal phase) is so called because you can control when you swallow food.

The Stomach

There are four main regions in the stomach: the cardia, fundus, body, and pylorus.

The cardia (or cardiac region) is the point where the esophagus connects to the stomach and through which food passes into the stomach.

The narrower end is called the pyloric canal, which connects to the duodenum.

In the absence of food, the stomach deflates inward, and its mucosa and submucosa fall into a large fold called a ruga.

Cells that make up the pyloric antrum secrete mucus and a number of hormones, including the majority of the stimulatory hormone, gastrin.

Located primarily in the middle region of the gastric glands are parietal cells, which are among the most highly differentiated of the body’s epithelial cells.

Located primarily in the basal regions of gastric glands are chief cells, which secrete pepsinogen, the inactive proenzyme form of pepsin.

Enteroendocrine cells found in the gastric glands secrete various hormones into the interstitial fluid of the lamina propria.

Gastric Secretion

The cephalic phase (reflex phase) of gastric secretion, which is relatively brief, takes place before food enters the stomach.

The gastric phase of secretion lasts 3 to 4 hours, and is set in motion by local neural and hormonal mechanisms triggered by the entry of food into the stomach.

The intestinal phase of gastric secretion has both excitatory and inhibitory elements.

The Mucosal Barrier

The stomach is protected from self-digestion by the mucosal barrier.

The mucosa of the stomach is exposed to the highly corrosive acidity of gastric juice.

Mechanical Digestion

A mixing wave is a unique type of peristalsis that mixes and softens the food with gastric juices to create chyme.

The Small and Large Intestines

Chyme released from the stomach enters the small intestine, which is the primary digestive organ in the body.

Also called a plica circulare, a circular fold is a deep ridge in the mucosa and submucosa.

Within the circular folds are small (0.5–1 mm long) hairlike vascularized projections called villi (singular = villus) that give the mucosa a furry texture.

As their name suggests, microvilli (singular = microvillus) are much smaller (1 μm) than villi.

The mucosa between the villi is dotted with deep crevices that each lead into a tubular intestinal gland (crypt of Lieberkühn), which is formed by cells that line the crevices.

The Large Intestine: The large intestine is the terminal part of the alimentary canal.

Subdivisions: The large intestine is subdivided into four main regions: the cecum, the colon, the rectum, and the anus.

Cecum

The first part of the large intestine is the cecum, a sac-like structure that is suspended inferior to the ileocecal valve.

The appendix (or vermiform appendix) is a winding tube that attaches to the cecum.

The mesoappendix, the mesentery of the appendix, tethers it to the mesentery of the ileum.

Colon

The cecum blends seamlessly with the colon.

At the inferior surface of the liver, the colon bends to form the right colic flexure (hepatic

flexure) and becomes the transverse colon.

After entering the pelvis inferiorly, it becomes the s-shaped sigmoid colon, which extends medially to the midline.

Rectum: Food residue leaving the sigmoid colon enters the rectum in the pelvis, near the third sacral vertebra.

Anal Canal: Food residue reaches the last part of the large intestine, the anal canal, which is located in the perineum, completely outside of the abdominopelvic cavity.

Anatomy

The teniae coli are three bands of smooth muscle that make up the longitudinal muscle layer of the muscularis of the large intestine, except at its terminal end.

The anal canal’s mucous membrane is organized into longitudinal folds, each called an anal column, which house a grid of arteries and veins.

Depressions between the anal columns, each called an anal sinus, secrete mucus that facilitates defecation.

The pectinate line (or dentate line) is a horizontal, jagged band that runs circumferentially just below the level of the anal sinuses, and represents the junction between the hindgut and external skin.

Mechanical Digestion

The presence of food residues in the colon stimulates a slow-moving haustral contraction.

Distension in the stomach and the breakdown products of digestion in the small intestine provoke the gastrocolic reflex, which increases motility, including mass movements, in the colon.

Accessory Organs in Digestion: The Liver, Pancreas, and Gallbladder

The liver is the largest gland in the body, weighing about three pounds in an adult.

The porta hepatis (“gate to the liver”) is where the hepatic artery and hepatic portal vein enter the liver.

A hepatocyte is the liver’s main cell type, accounting for around 80 percent of the liver's volume.

Plates of hepatocytes called hepatic laminae radiate outward from the portal vein in each hepatic lobule.

A hepatic sinusoid is an open, porous blood space formed by fenestrated capillaries from nutrient-rich hepatic portal veins and oxygen-rich hepatic arteries.

Bile is a mixture secreted by the liver to accomplish the emulsification of lipids in the small intestine.

Bilirubin, the main bile pigment, is a waste product produced when the spleen removes old or damaged red blood cells from the circulation.

The Pancreas

The soft, oblong, glandular pancreas lies transversely in the retroperitoneum behind the stomach.

The exocrine part of the pancreas arises as little grape-like cell clusters, each called an acinus (plural = acini), located at the terminal ends of pancreatic ducts.

The Gallbladder: The gallbladder is 8–10 cm (~3–4 in) long and is nested in a shallow area on the posterior aspect of the right lobe of the liver.

Chemical Digestion and Absorption: A Closer Look

The three lipases responsible for lipid digestion are lingual lipase, gastric lipase, and pancreatic lipase.

Two types of pancreatic nuclease are responsible for their digestion: deoxyribonuclease, which digests DNA, and ribonuclease, which digests RNA.

Knowt

Knowt