Breathing and Exchange of Gases

Respiratory Organs:

Mechanisms of breathing vary among different groups of animals depending mainly on their habitats and levels of the organization.

Lower invertebrates like sponges, coelenterates, flatworms, etc., exchange O2 with CO2 by simple diffusion over their entire body surface.

Earthworms use their moist cuticle and insects have a network of tubes (tracheal tubes) to transport atmospheric air within the body.

Special vascularised structures called gills (branchial respiration) are used by most aquatic arthropods and molluscs whereas vascularised bags called lungs (pulmonary respiration) are used by the terrestrial forms for the exchange of gases.

Among vertebrates, fishes use gills whereas amphibians, reptiles, birds, and mammals respire through lungs.

Amphibians like frogs can respire through their moist skin (cutaneous respiration) also.

Human Respiratory System:

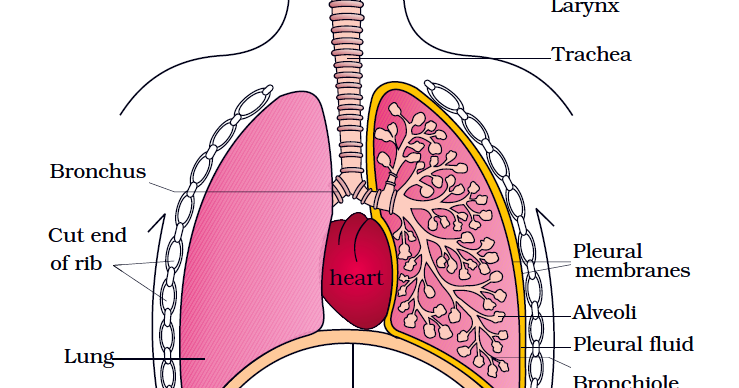

We have a pair of external nostrils opening out above the upper lips.

It leads to a nasal chamber through the nasal passage.

The nasal chamber opens into the pharynx, a portion of which is the common passage for food and air.

The pharynx opens through the larynx region into the trachea.

The larynx is a cartilaginous box that helps in sound production and is hence called the sound box.

During swallowing, the glottis can be covered by a thin elastic cartilaginous flap called epiglottis to prevent the entry of food into the larynx.

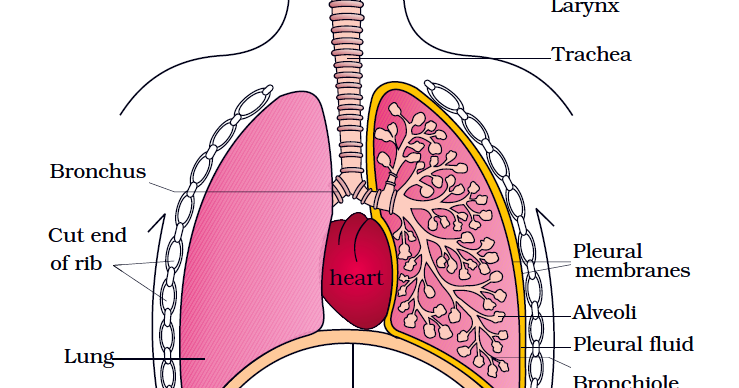

The trachea is a straight tube extending up to the mid-thoracic cavity, which divides at the level of the 5th thoracic vertebra into the right and left primary bronchi.

Each bronchus undergoes repeated divisions to form the secondary and tertiary bronchi and bronchioles ending up in very thin terminal bronchioles.

The tracheae, primary, secondary and tertiary bronchi, and initial bronchioles are supported by incomplete cartilaginous rings.

Each terminal bronchiole gives rise to a number of very thin, irregular-walled, and vascularised bag-like structures called alveoli.

The branching network of bronchi, bronchioles, and alveoli comprise the lungs.

We have two lungs that are covered by a double-layered pleura, with pleural fluid between them.

It reduces friction on the lung surface.

The outer pleural membrane is in close contact with the thoracic lining whereas the inner pleural membrane is in contact with the lung surface.

The part starting with the external nostrils up to the terminal bronchioles constitute the conducting part whereas the alveoli and their ducts form the respiratory or exchange part of the respiratory system.

The conducting part transports the atmospheric air to the alveoli, clears it from foreign particles, and humidifiers, and also brings the air to body temperature.

The exchange part is the site of actual diffusion of O2 and CO2 between blood and atmospheric air.

The lungs are situated in the thoracic chamber which is anatomically an air-tight chamber.

The thoracic chamber is formed dorsally by the vertebral column, ventrally by the sternum, laterally by the ribs, and on the lower side by the dome-shaped diaphragm.

The anatomical setup of lungs in the thorax is such that any change in the volume of the thoracic cavity will be reflected in the lung (pulmonary) cavity.

Such an arrangement is essential for breathing, as we cannot directly alter the pulmonary volume.

Respiration involves the following steps:

Breathing or pulmonary ventilation by which atmospheric air is drawn in and CO2-rich alveolar air is released out.

Diffusion of gases (O2 and CO2 ) across the alveolar membrane.

Transport of gases by the blood.

Diffusion of O2 and CO2 between blood and tissues.

Utilization of O2 by the cells for catabolic reactions and resultant release of CO2

Mechanism of Breathing:

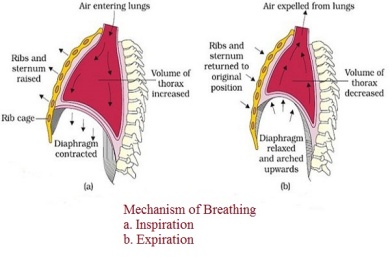

Breathing involves two stages:

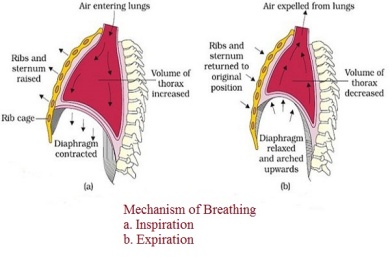

Inspiration is during which atmospheric air is drawn in.

Expiration is by which the alveolar air is released.

The movement of air into and out of the lungs is carried out by creating a pressure gradient between the lungs and the atmosphere.

Inspiration can occur if the pressure within the lungs (intra-pulmonary pressure) is less than the atmospheric pressure, i.e., there is a negative pressure in the lungs with respect to atmospheric pressure.

Similarly, expiration takes place when the intra-pulmonary pressure is higher than the atmospheric pressure.

The diaphragm and a specialized set of muscles – external and internal intercostals between the ribs, help in the generation of such gradients.

Inspiration is initiated by the contraction of the diaphragm which increases the volume of the thoracic chamber in the anteroposterior axis.

The contraction of external intercostal muscles lifts up the ribs and the sternum causing an increase in the volume of the thoracic chamber in the dorso-ventral axis.

The overall increase in the thoracic volume causes a similar increase in pulmonary volume.

An increase in pulmonary volume decreases the intra-pulmonary pressure to less than the atmospheric pressure which forces the air from outside to move into the lungs, i.e., inspiration.

Relaxation of the diaphragm and the inter-costal muscles returns the diaphragm and sternum to their normal positions and reduce the thoracic volume and thereby the pulmonary volume.

This leads to an increase in intra-pulmonary pressure to slightly above the atmospheric pressure causing the expulsion of air from the lungs, i.e., expiration.

We have the ability to increase the strength of inspiration and expiration with the help of additional muscles in the abdomen.

On average, a healthy human breathes 12-16 times/minute.

The volume of air involved in breathing movements can be estimated by using a spirometer which helps in the clinical assessment of pulmonary functions.

Respiratory Volumes and Capacities:

Respiratory Volumes and Capacities:

Tidal Volume:

The volume of air inspired or expired during normal respiration.

It is approx. 500 mL., i.e., a healthy man can inspire or expire approximately 6000 to 8000 mL of air per minute.

Inspiratory Reserve Volume (IRV):

It is the additional volume of air, that a person can inspire by a forcible inspiration.

This averages 2500 mL to 3000 mL.

Expiratory Reserve Volume (ERV):

It is the additional volume of air, that a person can expire by a forcible expiration.

This averages 1000 mL to 1100 mL.

Residual Volume (RV):

The volume of air remaining in the lungs even after a forcible expiration.

This averages 1100 mL to 1200 mL.

By adding up a few respiratory volumes described above, one can derive various pulmonary capacities, which can be used in clinical diagnosis.

Inspiratory Capacity (IC):

The total volume of air a person can inspire after a normal expiration.

This includes tidal volume and inspiratory reserve volume ( TV+IRV).

Expiratory Capacity (EC):

The total volume of air a person can expire after a normal inspiration.

This includes tidal volume and expiratory reserve volume (TV+ERV).

Functional Residual Capacity (FRC):

The volume of air that will remain in the lungs after a normal expiration.

This includes ERV+RV.

Vital Capacity (VC):

The maximum volume of air a person can breathe in after forced expiration.

This includes ERV, TV, and IRV, or the maximum volume of air a person can breathe out after a forced inspiration.

Total Lung Capacity (TLC):

A total volume of air accommodated in the lungs at the end of forced inspiration.

This includes RV, ERV, TV, and IRV or vital capacity + residual volume.

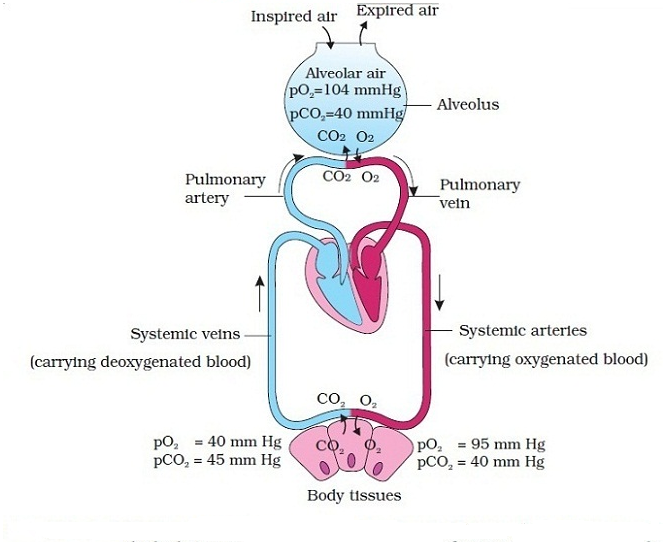

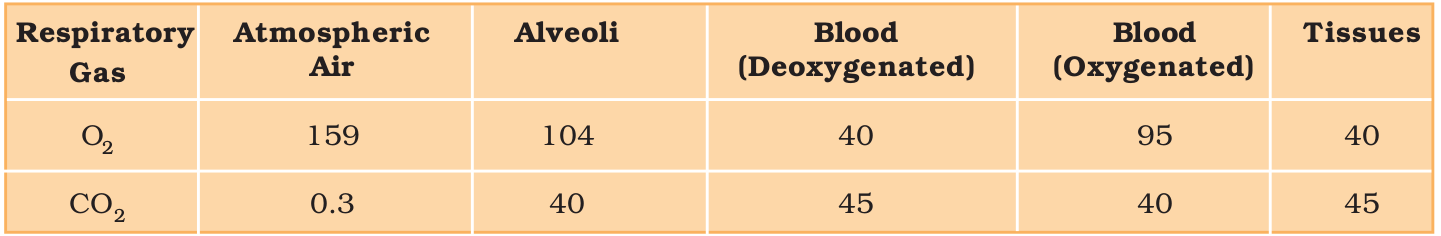

Exchange of Gases:

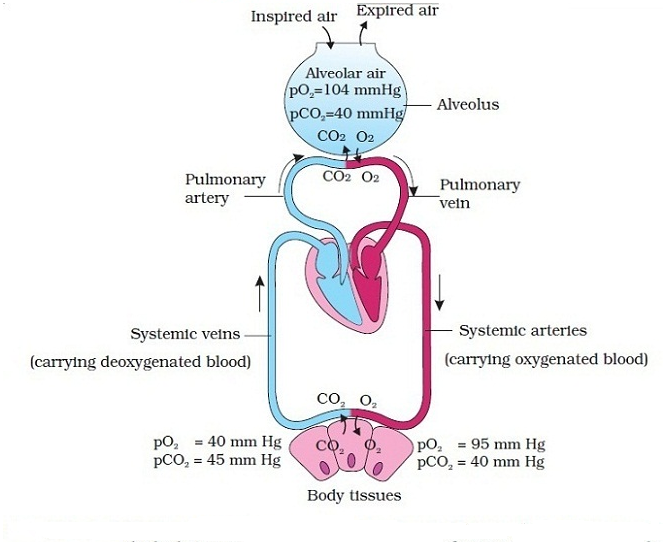

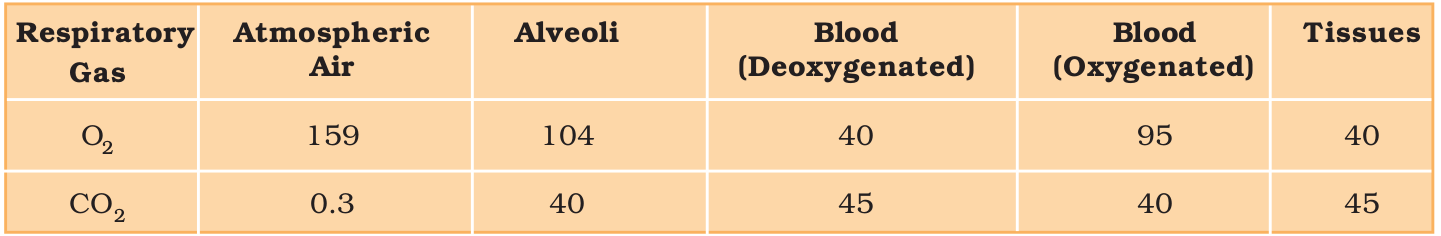

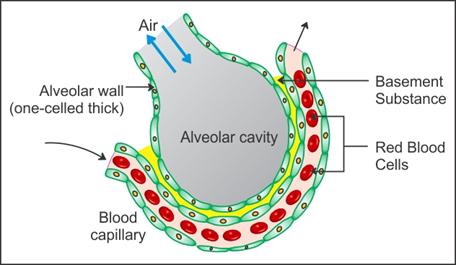

Alveoli are the primary sites of exchange of gases.

The exchange of gases also occurs between blood and tissues.

O2 and CO2 are exchanged in these sites by simple diffusion mainly based on pressure/concentration gradient.

Solubility of the gases as well as the thickness of the membranes involved in diffusion is also some important factors that can affect the rate of diffusion.

Pressure contributed by an individual gas in a mixture of gases is called partial pressure and is represented as pO2 for oxygen and pCO2 for carbon dioxide.

As the solubility of CO2 is 20-25 times higher than that of O2, the amount of CO2 that can diffuse through the diffusion membrane per unit difference in partial pressure is much higher compared to that of O2.

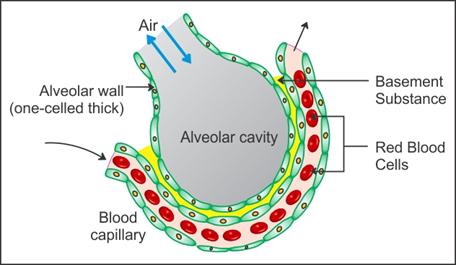

The diffusion membrane is made up of three major layers namely,

the thin squamous epithelium of alveoli

the endothelium of alveolar capillaries

the basement substance (composed of a thin basement membrane supporting the squamous epithelium and the basement membrane surrounding the single layer endothelial cells of capillaries) in between them.

However, its total thickness is much less than a millimeter.

Therefore, all the factors in our body are favourable for the diffusion of O2 from alveoli to tissues and that of CO2 from tissues to alveoli.

Transport of Gases:

Transport of Gases:

Blood is the medium of transport for O2 and CO2.

About 97 percent of O2 is transported by RBCs in the blood.

The remaining 3 percent of O2 is carried in a dissolved state through the plasma.

Nearly 20-25 per cent of CO2 is transported by RBCs whereas 70 per cent of it is carried as bicarbonate.

About 7 percent of CO2 is carried in a dissolved state through plasma.

Transport of Oxygen:

Haemoglobin is a red-coloured iron-containing pigment present in the RBCs.

O2 can bind with haemoglobin in a reversible manner to form oxyhaemoglobin.

Each haemoglobin molecule can carry a maximum of four molecules of O2.

The binding of oxygen with haemoglobin is primarily related to the partial pressure of O2.

The partial pressure of CO2, hydrogen ion concentration and temperature are the other factors which can interfere with this binding.

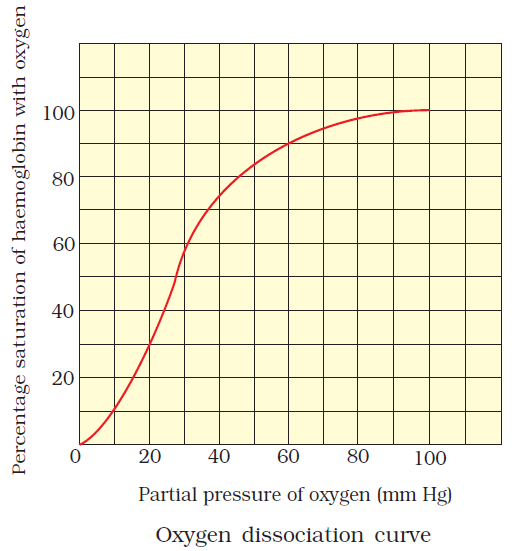

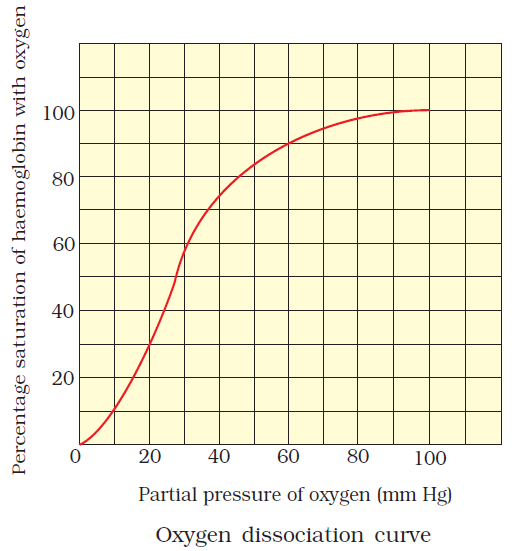

A sigmoid curve is obtained when the percentage saturation of haemoglobin with O2 is plotted against the pO2.

This curve is called the Oxygen dissociation curve and is highly useful in studying the effect of factors like pCO2, H+ concentration, etc., on the binding of O2 with haemoglobin.

In the alveoli, where there is high pO2, low pCO2, lesser H+ concentration and lower temperature, the factors are all favourable for the formation of oxyhaemoglobin, whereas, in the tissues, where low pO2, high pCO2, high H+ concentration and higher temperature exist, the conditions are favourable for dissociation of oxygen from the oxyhaemoglobin.

This clearly indicates that O2 gets bound to haemoglobin on the lung surface and gets dissociated in the tissues.

Every 100 ml of oxygenated blood can deliver around 5 ml of O2 to the tissues under normal physiological conditions.

Transport of Carbon Dioxide:

CO2 is carried by haemoglobin as carbamino-haemoglobin (about 20-25 per cent).

This binding is related to the partial pressure of CO2.

pO2 is a major factor which could affect this binding.

When pCO2 is high and pO2 is low as in the tissues, more binding of carbon dioxide occurs whereas, when the pCO2 is low and pO2 is high as in the alveoli, dissociation of CO2 from carbamino-haemoglobin takes place, i.e., CO2 which is bound to haemoglobin from the tissues is delivered at the alveoli.

RBCs contain a very high concentration of the enzyme, carbonic anhydrase and minute quantities of the same is present in the plasma too.

This enzyme facilitates the following reaction in both directions.

At the tissue site where the partial pressure of CO2 is high due to catabolism, CO2 diffuses into blood (RBCs and plasma) and forms HCO3 – and H+.

At the alveolar site where pCO2 is low, the reaction proceeds in the opposite direction leading to the formation of CO2 and H2O.

Thus, CO2 trapped as bicarbonate at the tissue level and transported to the alveoli is released out as CO2.

Every 100 ml of deoxygenated blood delivers approximately 4 ml of CO2 to the alveoli.

Regulation of Respiration:

Regulation of Respiration:

Human beings have a significant ability to maintain and moderate the respiratory rhythm to suit the demands of the body tissues.

This is done by the neural system.

A specialised centre present in the medulla region of the brain called the respiratory rhythm centre is primarily responsible for this regulation.

Another centre present in the pons region of the brain called pneumotaxic centre can moderate the functions of the respiratory rhythm centre.

The neural signal from this centre can reduce the duration of inspiration and thereby alter the respiratory rate.

A chemosensitive area is situated adjacent to the rhythm centre which is highly sensitive to CO2 and hydrogen ions.

An increase in these substances can activate this centre, which in turn can signal the rhythm centre to make necessary adjustments in the respiratory process by which these substances can be eliminated.

Receptors associated with the aortic arch and carotid artery also can recognise changes in CO2 and H+ concentration and send necessary signals to the rhythm centre for remedial actions.

The role of oxygen in the regulation of respiratory rhythm is quite insignificant.

Disorders of Respiratory System:

Asthma:

It is a difficulty in breathing causing wheezing due to inflammation of bronchi and bronchioles.

Emphysema:

It is a chronic disorder in which alveolar walls are damaged due to which the respiratory surface is decreased.

One of the major causes of this is cigarette smoking.

Occupational Respiratory Disorders:

In certain industries, especially those involving grinding or stone-breaking, so much dust is produced that the defence mechanism of the body cannot fully cope with the situation.

Long exposure can give rise to inflammation leading to fibrosis (proliferation of fibrous tissues) and thus causing serious lung damage.

Workers in such industries should wear protective masks.

Breathing and Exchange of Gases

Respiratory Organs:

Mechanisms of breathing vary among different groups of animals depending mainly on their habitats and levels of the organization.

Lower invertebrates like sponges, coelenterates, flatworms, etc., exchange O2 with CO2 by simple diffusion over their entire body surface.

Earthworms use their moist cuticle and insects have a network of tubes (tracheal tubes) to transport atmospheric air within the body.

Special vascularised structures called gills (branchial respiration) are used by most aquatic arthropods and molluscs whereas vascularised bags called lungs (pulmonary respiration) are used by the terrestrial forms for the exchange of gases.

Among vertebrates, fishes use gills whereas amphibians, reptiles, birds, and mammals respire through lungs.

Amphibians like frogs can respire through their moist skin (cutaneous respiration) also.

Human Respiratory System:

We have a pair of external nostrils opening out above the upper lips.

It leads to a nasal chamber through the nasal passage.

The nasal chamber opens into the pharynx, a portion of which is the common passage for food and air.

The pharynx opens through the larynx region into the trachea.

The larynx is a cartilaginous box that helps in sound production and is hence called the sound box.

During swallowing, the glottis can be covered by a thin elastic cartilaginous flap called epiglottis to prevent the entry of food into the larynx.

The trachea is a straight tube extending up to the mid-thoracic cavity, which divides at the level of the 5th thoracic vertebra into the right and left primary bronchi.

Each bronchus undergoes repeated divisions to form the secondary and tertiary bronchi and bronchioles ending up in very thin terminal bronchioles.

The tracheae, primary, secondary and tertiary bronchi, and initial bronchioles are supported by incomplete cartilaginous rings.

Each terminal bronchiole gives rise to a number of very thin, irregular-walled, and vascularised bag-like structures called alveoli.

The branching network of bronchi, bronchioles, and alveoli comprise the lungs.

We have two lungs that are covered by a double-layered pleura, with pleural fluid between them.

It reduces friction on the lung surface.

The outer pleural membrane is in close contact with the thoracic lining whereas the inner pleural membrane is in contact with the lung surface.

The part starting with the external nostrils up to the terminal bronchioles constitute the conducting part whereas the alveoli and their ducts form the respiratory or exchange part of the respiratory system.

The conducting part transports the atmospheric air to the alveoli, clears it from foreign particles, and humidifiers, and also brings the air to body temperature.

The exchange part is the site of actual diffusion of O2 and CO2 between blood and atmospheric air.

The lungs are situated in the thoracic chamber which is anatomically an air-tight chamber.

The thoracic chamber is formed dorsally by the vertebral column, ventrally by the sternum, laterally by the ribs, and on the lower side by the dome-shaped diaphragm.

The anatomical setup of lungs in the thorax is such that any change in the volume of the thoracic cavity will be reflected in the lung (pulmonary) cavity.

Such an arrangement is essential for breathing, as we cannot directly alter the pulmonary volume.

Respiration involves the following steps:

Breathing or pulmonary ventilation by which atmospheric air is drawn in and CO2-rich alveolar air is released out.

Diffusion of gases (O2 and CO2 ) across the alveolar membrane.

Transport of gases by the blood.

Diffusion of O2 and CO2 between blood and tissues.

Utilization of O2 by the cells for catabolic reactions and resultant release of CO2

Mechanism of Breathing:

Breathing involves two stages:

Inspiration is during which atmospheric air is drawn in.

Expiration is by which the alveolar air is released.

The movement of air into and out of the lungs is carried out by creating a pressure gradient between the lungs and the atmosphere.

Inspiration can occur if the pressure within the lungs (intra-pulmonary pressure) is less than the atmospheric pressure, i.e., there is a negative pressure in the lungs with respect to atmospheric pressure.

Similarly, expiration takes place when the intra-pulmonary pressure is higher than the atmospheric pressure.

The diaphragm and a specialized set of muscles – external and internal intercostals between the ribs, help in the generation of such gradients.

Inspiration is initiated by the contraction of the diaphragm which increases the volume of the thoracic chamber in the anteroposterior axis.

The contraction of external intercostal muscles lifts up the ribs and the sternum causing an increase in the volume of the thoracic chamber in the dorso-ventral axis.

The overall increase in the thoracic volume causes a similar increase in pulmonary volume.

An increase in pulmonary volume decreases the intra-pulmonary pressure to less than the atmospheric pressure which forces the air from outside to move into the lungs, i.e., inspiration.

Relaxation of the diaphragm and the inter-costal muscles returns the diaphragm and sternum to their normal positions and reduce the thoracic volume and thereby the pulmonary volume.

This leads to an increase in intra-pulmonary pressure to slightly above the atmospheric pressure causing the expulsion of air from the lungs, i.e., expiration.

We have the ability to increase the strength of inspiration and expiration with the help of additional muscles in the abdomen.

On average, a healthy human breathes 12-16 times/minute.

The volume of air involved in breathing movements can be estimated by using a spirometer which helps in the clinical assessment of pulmonary functions.

Respiratory Volumes and Capacities:

Respiratory Volumes and Capacities:

Tidal Volume:

The volume of air inspired or expired during normal respiration.

It is approx. 500 mL., i.e., a healthy man can inspire or expire approximately 6000 to 8000 mL of air per minute.

Inspiratory Reserve Volume (IRV):

It is the additional volume of air, that a person can inspire by a forcible inspiration.

This averages 2500 mL to 3000 mL.

Expiratory Reserve Volume (ERV):

It is the additional volume of air, that a person can expire by a forcible expiration.

This averages 1000 mL to 1100 mL.

Residual Volume (RV):

The volume of air remaining in the lungs even after a forcible expiration.

This averages 1100 mL to 1200 mL.

By adding up a few respiratory volumes described above, one can derive various pulmonary capacities, which can be used in clinical diagnosis.

Inspiratory Capacity (IC):

The total volume of air a person can inspire after a normal expiration.

This includes tidal volume and inspiratory reserve volume ( TV+IRV).

Expiratory Capacity (EC):

The total volume of air a person can expire after a normal inspiration.

This includes tidal volume and expiratory reserve volume (TV+ERV).

Functional Residual Capacity (FRC):

The volume of air that will remain in the lungs after a normal expiration.

This includes ERV+RV.

Vital Capacity (VC):

The maximum volume of air a person can breathe in after forced expiration.

This includes ERV, TV, and IRV, or the maximum volume of air a person can breathe out after a forced inspiration.

Total Lung Capacity (TLC):

A total volume of air accommodated in the lungs at the end of forced inspiration.

This includes RV, ERV, TV, and IRV or vital capacity + residual volume.

Exchange of Gases:

Alveoli are the primary sites of exchange of gases.

The exchange of gases also occurs between blood and tissues.

O2 and CO2 are exchanged in these sites by simple diffusion mainly based on pressure/concentration gradient.

Solubility of the gases as well as the thickness of the membranes involved in diffusion is also some important factors that can affect the rate of diffusion.

Pressure contributed by an individual gas in a mixture of gases is called partial pressure and is represented as pO2 for oxygen and pCO2 for carbon dioxide.

As the solubility of CO2 is 20-25 times higher than that of O2, the amount of CO2 that can diffuse through the diffusion membrane per unit difference in partial pressure is much higher compared to that of O2.

The diffusion membrane is made up of three major layers namely,

the thin squamous epithelium of alveoli

the endothelium of alveolar capillaries

the basement substance (composed of a thin basement membrane supporting the squamous epithelium and the basement membrane surrounding the single layer endothelial cells of capillaries) in between them.

However, its total thickness is much less than a millimeter.

Therefore, all the factors in our body are favourable for the diffusion of O2 from alveoli to tissues and that of CO2 from tissues to alveoli.

Transport of Gases:

Transport of Gases:

Blood is the medium of transport for O2 and CO2.

About 97 percent of O2 is transported by RBCs in the blood.

The remaining 3 percent of O2 is carried in a dissolved state through the plasma.

Nearly 20-25 per cent of CO2 is transported by RBCs whereas 70 per cent of it is carried as bicarbonate.

About 7 percent of CO2 is carried in a dissolved state through plasma.

Transport of Oxygen:

Haemoglobin is a red-coloured iron-containing pigment present in the RBCs.

O2 can bind with haemoglobin in a reversible manner to form oxyhaemoglobin.

Each haemoglobin molecule can carry a maximum of four molecules of O2.

The binding of oxygen with haemoglobin is primarily related to the partial pressure of O2.

The partial pressure of CO2, hydrogen ion concentration and temperature are the other factors which can interfere with this binding.

A sigmoid curve is obtained when the percentage saturation of haemoglobin with O2 is plotted against the pO2.

This curve is called the Oxygen dissociation curve and is highly useful in studying the effect of factors like pCO2, H+ concentration, etc., on the binding of O2 with haemoglobin.

In the alveoli, where there is high pO2, low pCO2, lesser H+ concentration and lower temperature, the factors are all favourable for the formation of oxyhaemoglobin, whereas, in the tissues, where low pO2, high pCO2, high H+ concentration and higher temperature exist, the conditions are favourable for dissociation of oxygen from the oxyhaemoglobin.

This clearly indicates that O2 gets bound to haemoglobin on the lung surface and gets dissociated in the tissues.

Every 100 ml of oxygenated blood can deliver around 5 ml of O2 to the tissues under normal physiological conditions.

Transport of Carbon Dioxide:

CO2 is carried by haemoglobin as carbamino-haemoglobin (about 20-25 per cent).

This binding is related to the partial pressure of CO2.

pO2 is a major factor which could affect this binding.

When pCO2 is high and pO2 is low as in the tissues, more binding of carbon dioxide occurs whereas, when the pCO2 is low and pO2 is high as in the alveoli, dissociation of CO2 from carbamino-haemoglobin takes place, i.e., CO2 which is bound to haemoglobin from the tissues is delivered at the alveoli.

RBCs contain a very high concentration of the enzyme, carbonic anhydrase and minute quantities of the same is present in the plasma too.

This enzyme facilitates the following reaction in both directions.

At the tissue site where the partial pressure of CO2 is high due to catabolism, CO2 diffuses into blood (RBCs and plasma) and forms HCO3 – and H+.

At the alveolar site where pCO2 is low, the reaction proceeds in the opposite direction leading to the formation of CO2 and H2O.

Thus, CO2 trapped as bicarbonate at the tissue level and transported to the alveoli is released out as CO2.

Every 100 ml of deoxygenated blood delivers approximately 4 ml of CO2 to the alveoli.

Regulation of Respiration:

Regulation of Respiration:

Human beings have a significant ability to maintain and moderate the respiratory rhythm to suit the demands of the body tissues.

This is done by the neural system.

A specialised centre present in the medulla region of the brain called the respiratory rhythm centre is primarily responsible for this regulation.

Another centre present in the pons region of the brain called pneumotaxic centre can moderate the functions of the respiratory rhythm centre.

The neural signal from this centre can reduce the duration of inspiration and thereby alter the respiratory rate.

A chemosensitive area is situated adjacent to the rhythm centre which is highly sensitive to CO2 and hydrogen ions.

An increase in these substances can activate this centre, which in turn can signal the rhythm centre to make necessary adjustments in the respiratory process by which these substances can be eliminated.

Receptors associated with the aortic arch and carotid artery also can recognise changes in CO2 and H+ concentration and send necessary signals to the rhythm centre for remedial actions.

The role of oxygen in the regulation of respiratory rhythm is quite insignificant.

Disorders of Respiratory System:

Asthma:

It is a difficulty in breathing causing wheezing due to inflammation of bronchi and bronchioles.

Emphysema:

It is a chronic disorder in which alveolar walls are damaged due to which the respiratory surface is decreased.

One of the major causes of this is cigarette smoking.

Occupational Respiratory Disorders:

In certain industries, especially those involving grinding or stone-breaking, so much dust is produced that the defence mechanism of the body cannot fully cope with the situation.

Long exposure can give rise to inflammation leading to fibrosis (proliferation of fibrous tissues) and thus causing serious lung damage.

Workers in such industries should wear protective masks.

Knowt

Knowt