Chapter 5: Etruscan Art

Key Notes

Time Period

10th century B.C.E. to c. 270 B.C.E.

Height: 7th–6th centuries B.C.E.

Culture, beliefs, and physical settings

Etruscan art was produced in central Italy.

Etruscan art is studied as a unit, rather than by individual city-states.

Etruscan art evinces a long tradition of epic storytelling.

Art Making

Etruscan art reflects influences from other ancient traditions.

Cultural Interactions

There is an active exchange of artistic ideas throughout the Mediterranean.

Etruscan works of architecture and sculpture were influenced by their Greek counterparts.

Audience, functions and patron

Etruscan art expresses republican values.

Etruscan art shows evidence of large public monuments.

Theories and Interpretations

Etruscan art is defined by contemporary Roman observers as well as by modern archaeological efforts.

Little survives of the Etruscan written record.

Historical Background

The Etruscans are the people who lived in Italy before the arrival of the Romans.

Although they heavily influenced the Romans, their language and customs were different.

The ravages of time have destroyed much of what the Etruscans accomplished, but fortunately their sophisticated tombs in huge necropoli still survive in sufficient numbers to give us some idea of Etruscan life and art.

Eventually the Romans swallowed Etruscan culture whole, taking from it what they could use.

Etruscan Architecture

Much of what is known about the Etruscans comes from their tombs, which are arranged in densely packed necropoli throughout the Italian region of Tuscany, an area named for the Etruscans.

Most tombs are round with a door leading to a large, brightly painted interior chamber.

Etruscan symbols decorate these tombs.

Families and servants are buried together.

Little is known about Etruscan temples, except what can be gleaned from the Roman architect Vitruvius, who wrote about them extensively.

Etruscan buildings were made of wood and mud brick, not stone.

There is a flight of stairs leading up to the principal entrance, not a uniform set of steps surrounding the whole building.

Sculptures were placed on the rooftops, unlike in Greek temples, to announce the presence of the deity within.

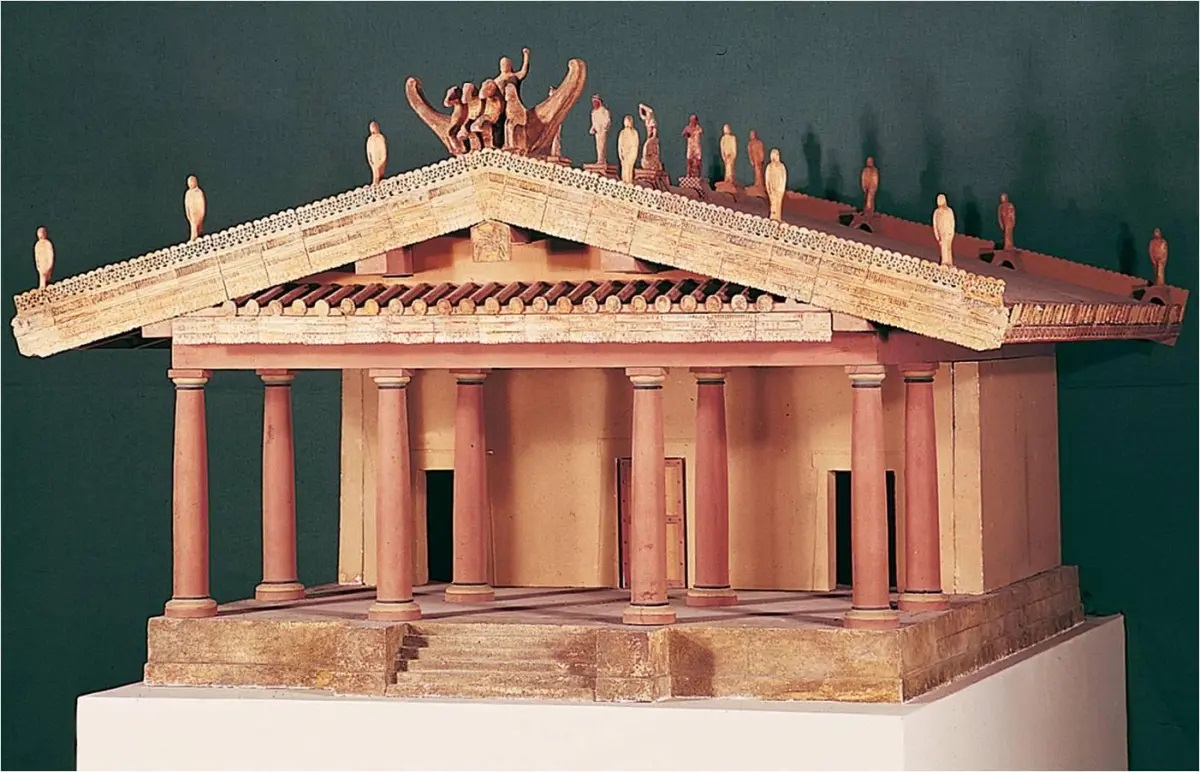

➼ Temple of Minerva

Details

510–500 B.C.E.

Made of mud brick or tufa (volcanic rock) and wood,

Found in Veii (near Rome), Italy

Form

Little architecture survives; this model is drawn from descriptions by Vitruvius, a Roman architect of the first century B.C.E.

Temple raised on a podium; defined visible entrance.

Deep porch places doorways away from the steps.

Function: Temple dedicated to the goddess Minerva, the Etruscan equivalent to the Greek Athena.

Materials: Temple made of mud brick and wood, perishable materials.

Context

Steps in front direct attention to the deep porch; entrances emphasized.

Three doors represent three gods; the interior divided into three spaces.

Etruscan variation of Greek capitals, called the Tuscan order.

Tuscan order: an order of ancient architecture featuring slender, smooth columns that sit on simple bases; no carvings on the frieze or in the capitals

Inspired by Greek architecture, but different:

Columns are unfluted and made of wood, not marble as in Greece.

Pediments are made of wood and contain no sculpture, as in Greece.

Etruscan columns were spaced further apart than Greek columns because they were made of lighter material.

Etruscans used sculptures made of terra cotta rather than stone on their roofs; columns are unfluted, made of wood, not marble as in Greece.

Images

Etruscan Painting

What survives of Etruscan painting is funerary, done on the walls and ceilings of tombs—some 280 painted chambers are still extant.

Brightly painted frescoes reveal a world full of cheerful Etruscans celebrating, dancing, eating, and playing musical instruments.

Much of the influence is probably Greek, but even fewer Greek painting from this period survives, so it is hard to draw firm parallels.

Tufa: a porous rock similar to limestone

Tumulus (plural: tumuli): an artificial mound of earth and stones placed over a grave

➼ Tomb of the Triclinium

Details

c. 480–470 B.C.E.

Made of tufa and fresco

Found in Tarquinia, Italy

Triclinium: a dining table in ancient Rome that has a couch on three sides for reclining at meals

Form

Ancient convention of men painted in darker colors than women.

Polychrome checkerboard pattern on ceiling; circles may symbolize time; pattern may reflect motifs on fabric tents erected for funeral banquets.

Function: Painted tomb in an Etruscan necropolis.

Content

Funerals seen as moments in which to celebrate the life of the deceased.

Dancing figures play musical instruments in a festive celebration of the dead.

Trees spring up between the main figures, and shrubbery grows beneath the reclining couches—perhaps suggesting a rural setting.

Context

Banqueting couples recline while eating in the ancient manner.

Named after a triclinium, an ancient Roman dining table, which appears in the fresco.

Image

Etruscan Sculpture

Etruscans preferred terra cotta, stucco, and bronze for their sculpture; on occasion, stonework was introduced.

Stucco: a fine plaster used for wall decorations or moldings

Terra cotta sculptures were modeled rather than carved.

The firing of large-scale works in a kiln betrays great technological prowess.

Most Etruscan sculpture shows an awareness of Greek Archaic art, although the comparisons go only so far.

For the Etruscans, whose terra cotta work was brilliantly painted, figures move dynamically in space, aware of the world around them. The Etruscans avoided nudity.

➼ Sarcophagus of the Spouses

Details

c. 520 B.C.E.

Made of terra cotta,

Found in Museo Nazionale di Villa Giulia, Rome

Form

Full-length portraits.

Great concentration on the upper bodies, less on the legs.

Bodies make an unnatural L-shape at the waist.

Broad shoulders, knotted hair, and simple anatomical details.

Function: Sarcophagus of a married couple, whose ashes were placed inside, or perhaps a large urn used for the ashes of the dead.

Technique: Large terra cotta construction made in four separate pieces and joined together.

Terra cotta: a hard ceramic clay used for building or for making pottery

Content

Both once held objects in their hands—perhaps the man held an egg to symbolize life after death; other theories suggest the woman is holding a bottle of perfume or a pomegranate.

The couple reclines against wineskins that act as cushions; the wineskins allude to the ceremony of sharing wine at funerary rituals.

Context

Depicts the ancient tradition of reclining while eating; men and women ate together, unlike in ancient Greece.

Symbiotic relationship, the man has a protective arm around the woman and the woman feeds the man, reflecting the high standing women had in Etruscan society.

Image

➼ Apollo from Veii

Details

Vulca — the master sculptor.

c. 510 B.C.E.

Made of terra cotta

Found in Museo Nazionale di Villa Giulia, Rome

Form

Figure has spirit, strides quickly forward.

Archaic Greek smile.

Meant to be seen from below.

Tightly fitting garment.

Hair in knots, dangles down around shoulders.

Originally brightly painted.

Materials: Masterpiece of terra cotta casting.

Context

Unlike Greek sculpture, which appears in pediments and is made of stone, Etruscans prefer terra cotta figures that are mounted on roof lines.

One of four large figures that once stood on the roof of the temple at Veii.

Part of a scene from Greek mythology involving the third labor of Hercules; Apollo looks directly at Hercules, an important figure in Etruscan religion.

May have been carved by Vulcan of Veii, the most famous Etruscan sculptor of the age.

Image

Chapter 5: Etruscan Art

Key Notes

Time Period

10th century B.C.E. to c. 270 B.C.E.

Height: 7th–6th centuries B.C.E.

Culture, beliefs, and physical settings

Etruscan art was produced in central Italy.

Etruscan art is studied as a unit, rather than by individual city-states.

Etruscan art evinces a long tradition of epic storytelling.

Art Making

Etruscan art reflects influences from other ancient traditions.

Cultural Interactions

There is an active exchange of artistic ideas throughout the Mediterranean.

Etruscan works of architecture and sculpture were influenced by their Greek counterparts.

Audience, functions and patron

Etruscan art expresses republican values.

Etruscan art shows evidence of large public monuments.

Theories and Interpretations

Etruscan art is defined by contemporary Roman observers as well as by modern archaeological efforts.

Little survives of the Etruscan written record.

Historical Background

The Etruscans are the people who lived in Italy before the arrival of the Romans.

Although they heavily influenced the Romans, their language and customs were different.

The ravages of time have destroyed much of what the Etruscans accomplished, but fortunately their sophisticated tombs in huge necropoli still survive in sufficient numbers to give us some idea of Etruscan life and art.

Eventually the Romans swallowed Etruscan culture whole, taking from it what they could use.

Etruscan Architecture

Much of what is known about the Etruscans comes from their tombs, which are arranged in densely packed necropoli throughout the Italian region of Tuscany, an area named for the Etruscans.

Most tombs are round with a door leading to a large, brightly painted interior chamber.

Etruscan symbols decorate these tombs.

Families and servants are buried together.

Little is known about Etruscan temples, except what can be gleaned from the Roman architect Vitruvius, who wrote about them extensively.

Etruscan buildings were made of wood and mud brick, not stone.

There is a flight of stairs leading up to the principal entrance, not a uniform set of steps surrounding the whole building.

Sculptures were placed on the rooftops, unlike in Greek temples, to announce the presence of the deity within.

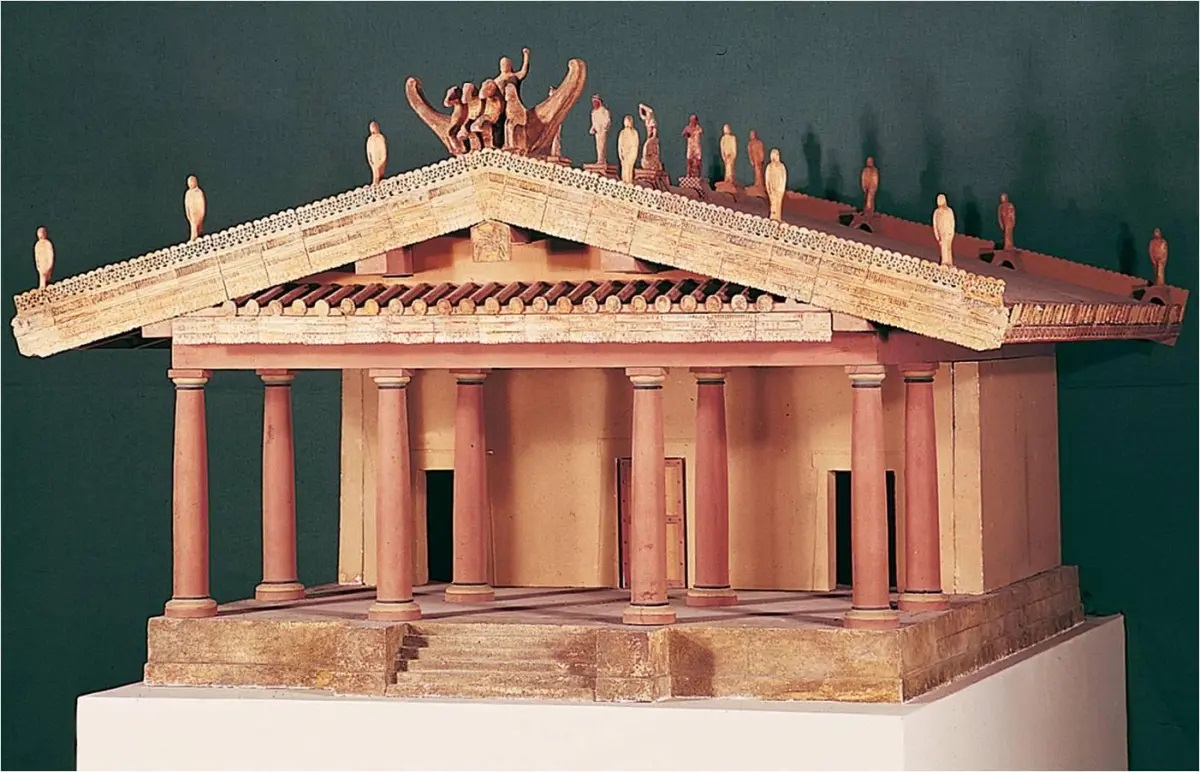

➼ Temple of Minerva

Details

510–500 B.C.E.

Made of mud brick or tufa (volcanic rock) and wood,

Found in Veii (near Rome), Italy

Form

Little architecture survives; this model is drawn from descriptions by Vitruvius, a Roman architect of the first century B.C.E.

Temple raised on a podium; defined visible entrance.

Deep porch places doorways away from the steps.

Function: Temple dedicated to the goddess Minerva, the Etruscan equivalent to the Greek Athena.

Materials: Temple made of mud brick and wood, perishable materials.

Context

Steps in front direct attention to the deep porch; entrances emphasized.

Three doors represent three gods; the interior divided into three spaces.

Etruscan variation of Greek capitals, called the Tuscan order.

Tuscan order: an order of ancient architecture featuring slender, smooth columns that sit on simple bases; no carvings on the frieze or in the capitals

Inspired by Greek architecture, but different:

Columns are unfluted and made of wood, not marble as in Greece.

Pediments are made of wood and contain no sculpture, as in Greece.

Etruscan columns were spaced further apart than Greek columns because they were made of lighter material.

Etruscans used sculptures made of terra cotta rather than stone on their roofs; columns are unfluted, made of wood, not marble as in Greece.

Images

Etruscan Painting

What survives of Etruscan painting is funerary, done on the walls and ceilings of tombs—some 280 painted chambers are still extant.

Brightly painted frescoes reveal a world full of cheerful Etruscans celebrating, dancing, eating, and playing musical instruments.

Much of the influence is probably Greek, but even fewer Greek painting from this period survives, so it is hard to draw firm parallels.

Tufa: a porous rock similar to limestone

Tumulus (plural: tumuli): an artificial mound of earth and stones placed over a grave

➼ Tomb of the Triclinium

Details

c. 480–470 B.C.E.

Made of tufa and fresco

Found in Tarquinia, Italy

Triclinium: a dining table in ancient Rome that has a couch on three sides for reclining at meals

Form

Ancient convention of men painted in darker colors than women.

Polychrome checkerboard pattern on ceiling; circles may symbolize time; pattern may reflect motifs on fabric tents erected for funeral banquets.

Function: Painted tomb in an Etruscan necropolis.

Content

Funerals seen as moments in which to celebrate the life of the deceased.

Dancing figures play musical instruments in a festive celebration of the dead.

Trees spring up between the main figures, and shrubbery grows beneath the reclining couches—perhaps suggesting a rural setting.

Context

Banqueting couples recline while eating in the ancient manner.

Named after a triclinium, an ancient Roman dining table, which appears in the fresco.

Image

Etruscan Sculpture

Etruscans preferred terra cotta, stucco, and bronze for their sculpture; on occasion, stonework was introduced.

Stucco: a fine plaster used for wall decorations or moldings

Terra cotta sculptures were modeled rather than carved.

The firing of large-scale works in a kiln betrays great technological prowess.

Most Etruscan sculpture shows an awareness of Greek Archaic art, although the comparisons go only so far.

For the Etruscans, whose terra cotta work was brilliantly painted, figures move dynamically in space, aware of the world around them. The Etruscans avoided nudity.

➼ Sarcophagus of the Spouses

Details

c. 520 B.C.E.

Made of terra cotta,

Found in Museo Nazionale di Villa Giulia, Rome

Form

Full-length portraits.

Great concentration on the upper bodies, less on the legs.

Bodies make an unnatural L-shape at the waist.

Broad shoulders, knotted hair, and simple anatomical details.

Function: Sarcophagus of a married couple, whose ashes were placed inside, or perhaps a large urn used for the ashes of the dead.

Technique: Large terra cotta construction made in four separate pieces and joined together.

Terra cotta: a hard ceramic clay used for building or for making pottery

Content

Both once held objects in their hands—perhaps the man held an egg to symbolize life after death; other theories suggest the woman is holding a bottle of perfume or a pomegranate.

The couple reclines against wineskins that act as cushions; the wineskins allude to the ceremony of sharing wine at funerary rituals.

Context

Depicts the ancient tradition of reclining while eating; men and women ate together, unlike in ancient Greece.

Symbiotic relationship, the man has a protective arm around the woman and the woman feeds the man, reflecting the high standing women had in Etruscan society.

Image

➼ Apollo from Veii

Details

Vulca — the master sculptor.

c. 510 B.C.E.

Made of terra cotta

Found in Museo Nazionale di Villa Giulia, Rome

Form

Figure has spirit, strides quickly forward.

Archaic Greek smile.

Meant to be seen from below.

Tightly fitting garment.

Hair in knots, dangles down around shoulders.

Originally brightly painted.

Materials: Masterpiece of terra cotta casting.

Context

Unlike Greek sculpture, which appears in pediments and is made of stone, Etruscans prefer terra cotta figures that are mounted on roof lines.

One of four large figures that once stood on the roof of the temple at Veii.

Part of a scene from Greek mythology involving the third labor of Hercules; Apollo looks directly at Hercules, an important figure in Etruscan religion.

May have been carved by Vulcan of Veii, the most famous Etruscan sculptor of the age.

Image

Knowt

Knowt