CIE A2 Level English: Language Change

Foreword: these notes were made in collaboration with a friend due to the complexity of the topic; I only take half of the ownership of these notes. By sharing this, I do hope people find the topic less daunting than it seems.

HISTORY OF LANGUAGE CHANGE

Old English (400 – 1150)

YEAR | STATE OF BRITAIN | LANGUAGE |

|---|---|---|

Pre 5th century | Occupied by original inhabitants of the British Isles | Celtic languages |

410 | Romans leave Britain after invading 3 times | Latin |

700 | Vikings invade | Old English/Anglo-Saxon (parts of the Scandinavian language became integrated eg family, animals) |

1066 | Norman conquest | Latin (church, learning) |

1362 (Middle English) | ME becomes the official language of the court | Middle English |

Middle English (1150 – 1450)

Anglo-Norman became the standard literary language and eventually, the language of the court in this time period.

Sound system had undergone dramatic changes but the spelling had barely changed. The French scribes updated the spelling of many English sounds and English gained 10,000 new words in this period.

New grammatical constructions came about, especially with the merging of Old English and Old French lexis. The word ‘unreasonable’ came from the Old English prefix ‘un’ and the Old French word ‘raisonable’.

FEATURES OF MIDDLE ENGLISH:

Simple grammar

Inflections disappeared and relatively uninflected (all plurals ended in -s, -es and -en)

Reflected shared languages

1000s of Latin words replaced Old English

Heavily influenced by French lexis (namely legal, religious and administrative lexis)

Vowels became shorter, would degrade into an indeterminate sound

No standardised form of spelling

After the Black Death (also known as the Black Plague) in 1348–50, the remaining working class grew in importance. English regained its status as Anglo-Norman became less used.

By the 14th century, Oxford University decreed that all students must speak English, as well as French. However, by the 15th century, the language took on 4 different dialects: Northern, East Midland, West Midland, and Southern, including a small sub-dialect of Kentish.

The East Midland and London dialects grew in prominence, particularly after William Caxton’s introduction of the printing press to England where he wrote in the East Midland dialects. The dialect also managed to survive due to:

geography — it had elements from both North and South dialects and was seen as a compromise between them

economic influence — the region had the largest and wealthiest people; agriculturally rich out of all the regions

academic influence — Oxford and Cambridge (which conducted their education in East Midland and London dialects) were of high intellectual influence

London as the capital — London was the commercial, political, legal, and social capital of the country

Linguistic Features of Archaic Texts

Lexis | words that are often no longer used e.g thee, thou, bacchanalia; could show archaic views on gender compared to modern day such as taboo terms |

|---|---|

Syntax | sentence structure that is not considered ‘correct’ now e.g Sometime too hot the eye of heaven shines |

Inflections | affixation at the beginning or end of words is no longer used e.g -eth (seemeth) or -est (whilest) |

Interchangeable letters | u and v were both used for the ‘u’ sound of words e.g Vnkle → uncle; also occurred to y & i and s and the medial s (ſ) |

Latinate lexis | words borrowed from Latin; usually have multiple syllables and their meanings tend to be more broad, abstract, or scientific e.g Anglo-Saxon ‘see’ vs Latinate ‘perceive’ |

French lexis | words borrowed from French, many related to politics e.g plebiscite, sovereignty, coup d’etat |

Non-standard spelling | some lexis would be spelled based on phonology or the writer’s knowledge e.g ‘fixt’ vs ‘fixed’ |

Inconsistent spelling | words spelled differently in the same text |

Pronunciation | doubling of vowels, an extra ‘e’ on the ends of words, double consonants to make long vowel sounds |

Early Modern English (1470 – 1800)

1400-1700s: Great Vowel shift

Pronunciation had shifted however spelling stayed the same due to the use of the same printing presses

1476: William Caxton brought the printing press to England

Greek and Latin texts were translated to English

Standardisation of English began

Punctuation and syntax features:

Virgule (/) or oblique stroke was everywhere

Full stop at different heights

Capitalisation was random with none for proper nouns

Colons were very common and had a broad range of use

Semi-colons were everywhere

Sentences could be 20+ lines long with a wide use of ‘and’ and ‘then’ coordinates

No paragraphs

1500s: Large use of printing in the 16th century

Books were luxury items and took weeks to months to create

Literacy rates exploded and prompted a new social dilemma

Double vowels (soon) and consonants (sitting) became widely used

Silent e used to mark the long length of a vowel sound (name)

All words that an author deemed important were capitalised

1500-1660: The Renaissance

Renewed respect for Classical literature and the arts

influence in Greek and Latin

Neologisms usually taken from Greek and Latin

Huge expansion of travel trade and colonialism accounted for large imports of foreign words, especially European

10,000-12,000 new words appeared in the English language

Following French practices, apostrophes were used when a vowel was omitted (lov’d)

u+v, i+j, y+i had no fixed phonetic values, used interchangeably

‘e‘ still found at the end of words

spelling is still irregular

Most shifts had occurred by the end of the Renaissance

1530-1600: The Reformation

Puritan moral beliefs and science heavily influenced texts and behaviours

1564-1616: Shakespeare

Many Shakespearean coinages entered the English Language such as eventful, laughable

John Hart was a spelling reformer who tried to introduce books on orthography and English spelling

John Hart also tried to establish capitalisation rules by saying anything deemed important by the writer should be capitalised

1611: The King James Bible

The KJB brought a standard version of the Bible to all people, many other versions of the Bible varied greatly

Much more conservative style of writing than Shakespeare

Contained grammar, forms and construction that were out of use elsewhere

1660-1688: The Restoration

Expansion in colonial trade saw more contact language

Revival of drama and literature, and new scientific discoveries, philosophical concepts and social and economic conditions

1755: Samuel Johnson’s dictionary

Standardisation became more prevalent

Spelling have begun to be codified

Apostrophes were eventually used as we do today

Paragraphs were in use

1762: Robert Lowth’s ‘Short Introduction to English Grammar’

Grammar standardisation; had 200 pages of arbitrary idiosyncratic rules on which grammatical forms should be avoided and encouraged

“two negatives in English destroy one another, or are equivalent to an affirmative”

“never put a preposition at the end of a sentence”

Late Modern English (1800 - Present)

Most prominent change was an expansion of lexis due to industrial and social developments, and colonialism. However, with changes came reactionaries.

This was a result of the Industrial Revolution (1760-1840) in which new words were introduced to describe new technology. Therefore, the language change was mostly lexical, making it similar to EME in terms of grammar and spelling rules. Noah Webster published his dictionary (1828), which differentiated American English from British English.

American English removes ‘u’ after ‘o’ (color vs colour), removes an ‘l’ in verbs (traveling vs travelling), switches s/c, z/s and a/e (defense vs defence, realize vs realise, and gray vs grey) and adds an ‘l’ at the end of words (fulfill vs fulfil).

The internet also brought forth a wide new range of jargon and the rapid spread of new lexis.

However, prescriptivists believed in following the rules of Latin as it was the historical language of the Bible, the law and courts, the classics, and of educated society;

Latin was seen as a pure and authoritative language with strict, unchanging rules unlike English. Although, the language has remained dead as it is not the language now for common communication

ESSAY APPLICATION:

Spread of literacy and mass production of printed word solidified standardisation and literacy as everyone had access to written English

American English was becoming a language of its own with distinguished orthographical spelling

Conversations and lexis shortened - abbreviations, telescoping, clipping

Hashtags and emojis reduce the number of words used

Grammatical rules have been discarded in texting due to the informal register necessary between friends

English has spread and become a global form of communication - many cultures have their own dialects and forms.

LANGUAGE CHANGE VIEWS

Reasons for Language Change

individuals — Chaucer, Shakespeare

Chaucer was one of the first people to write in English rather than French after the Norman invasion. His Canterbury Tales in the late 14th century was written in English Vernacular (the English spoken by the people in the East Midlands, which then became a prominent dialect) and his works attributed to the creation of iambic pentameter and the rhyme royal

Shakespeare is noted to have brought many new lexis to the English language, such as laughable and lacklustre, as well as many idioms. such as ‘seen better days’ and ‘slept not one wink’

technology — the printing press, typewriters, the internet; David Crystal believed that language change occurs due to these technological advancements

society — cultural changes and shifts

conscious change — change from above such as dominating social positions

unconscious change — change from below, those adapting language according to their own social needs, such as dialects

political correctness;

refrain from causing emotional harm (pragmatics)

assimilation into society

taboo

used for comedic effect

convergence or divergence

used as a filler or to show pain and displeasure

negative views

too much on TV

foreign influence i.e through trade, film, and music

new scientific discoveries and/or inventions

travel, trade, and colonisation — lexical changes as people adopt the other language for better customer service; accommodation theory

loanwords/borrowing

affixation

compounding

blending

conversion

shortening/abbreviation

acronyms

initialism

broadening/generalisation

globalisation — English becoming the language of trade and business

internal factors — language changes within itself

Prescriptivism vs Descriptivism

Prescriptivism: dictate how language should be used; believe in a more ‘correct’ form of English; refrains from change; reactionary

Lynne Truss: ‘Proper punctuation is both the sign and the cause of clear thinking’, ‘To those who care about punctuation, a sentence such as “Thank God its Friday” rouses feelings not only of despair but of violence’

John Humphrys (declinist prescriptivist): ‘They are destroying it: pillaging our punctuation; savaging our sentences; raping our vocabulary. And they must be stopped!’

Kathy August: ‘Slang doesn’t really give the right impression of a person’

S.K Ratcliffe: ‘the language is going to pieces before our eyes, especially under the influence of the Debased dialect of the cockney’

Robert Lowthe: ‘Our language is extremely imperfect, … it offends against every part of grammar.’

John Walker, author of A Critical Pronouncing Dictionary (1791): people with Scottish or Irish accents, Londoners with a Cockney accent sounded ‘a thousand times more offensive and disgusting’

Descriptivism: accept language change is inevitable and accept change; revolutionary

David Crystal: ‘no two high tides are the same’, ‘no changes are for the better; nor for the worst; they’re just changes’

Oliver Kamm: ‘prescriptivists want a ‘golden society’ that never existed’, ‘English is a river; it flows through many tributaries’

James Milroy: ‘There was no Golden Age’

Julie Blake: ‘to attempt to fix language is laughable… a futile attempt to defy… human nature’

‘the ideal campaign of a worthy dictionary was descriptive, not prescriptive … like the English language, [it would] live and breathe and change.’

John Ayto (lexicographer): ‘Words are a mirror of their times.’

Peter Trudgill: ‘Languages are self-regulating systems which can be left to take care of themselves’

Jean Aitchison’s Three Metaphors

Crumbling castle view - depicts the English language as an old building that must be preserved

Implies that there was once a peak of perfection in English (Golden Age) but no one can say when this date would have even been.

John Simon: “language should be treated like parks… available for properly respectful use but not for defacement or destruction”

If one part of the castle breaks, the rest falls if it is not immediately fixed

Infectious disease view - people catch language changes from those around them and must fight these diseases

In reality, people pick up changes because they want to

People change to adapt to social groups, such as jocks in a Detroit school copying standard adult speech while burnouts moved away from it.

Damp spoon syndrome view - laziness and sloppiness cause most language change

Omission of syllables at the end of words allows speech to speed up

Efficiency of speech

Dennis Freeborn’s Three Views

Incorrectness View — all accents are incorrect compared to Standard English and Received Pronunciation

Popularity of certain accents originates in fashion and convention but is not ‘correct’

Ugliness View — accents that aren’t Received Pronunciation don’t sound nice; they have negative connotations and stereotypes

This is commonly given to the Scouse accent associated with Liverpool in England; also known as Liverpool English or Merseyside English

Northern and Central Scouse sounds harsh, nasal, and fast

Southern Scouse is more slow, soft, and dark

often found in poorer urban areas

Impreciseness View — some accents are just ‘lazy’ and ‘sloppy’

Estuary English is a dialect where sounds are either ommitted or changed

The Inkhorn Controversy: a discussion over the use of foreign words in the English language

By the 15th and 16th centuries, between 10,000 to 25,000 new words were found in the English language, largely originating from Latin and Greek roots. These words became known as ‘inkhorn terms’ or ‘inkhornisms’.

Those who supported the inkhorns were:

Thomas Elyot

Georgie Pettie; ’for what word can be more plaine then this word plaine, and yet what can come more neere to Latine?’

Ben Jonson; ‘Yet we must adventure; for things at first hard and rough are by use made tender and gentle.’

Those who were against inkhornisms were:

Thomas Wilson; ‘if some of their mothers were alive, thei were not able to tell what they say’

John Cheke; ‘our tung shold be written cleane and pure, vnmixt and vnmangeled with borowing of other tunges’

THEORIES AND THEORISTS

Functional Theory by Michael Halliday

Language changes to suit the needs of the users, who need words to describe new ideas and objects, and ways to express themselves and their social identity

According to the functional theory, lexis is not actively discarded, but rather evolves until it is obsolete.

To look for in a text: LEXIS

Neologisms and coinage

Abbreviations, contractions, clippings, back-formations

Archaisms and obsolete lexis

Colloquialisms and slang

Jargon

Communication Accommodation Theory by Howard Giles

Like the Functional Theory, speakers change the way they speak and the way they utilise language depending on who they are speaking to.

Giles believed in the idea of ‘convergence’, where people make their language more like the person they are talking to in order to accommodate the other speaker — this makes the receiver feel more appreciative and valued. This includes speaking slower, using the other person’s local slang, or diluting our accents.

Case Study: Matha’s Vineyard by William Labov (1963)

William Labov was studying phonological variation, particularly in diphthongs. He conducted his study on an island called Martha’s Vineyard off the northeast coast of America.

Labov interviewed 69 different people people of varying age, race, and social groups. The questions he used subconsciously urged the participants to use words which contained the desired vowels he intended to study. Some interview questions he used were:

“When we speak of the right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, what does right mean? … Is it in writing?”

“If a man is successful at a job he doesn’t like, would you still say he was a successful man?”

His results found that phonological variation was based on social loyalty. Those who intended to stay on the island spoke with a more centralised accent that was farther from mainland pronunciations while those who wished to leave spoke with less centralisation with the intention to go to the mainland.

Cultural Transmission Theory from various theorists such as Hartl and Clark (1997), Bandura (1977), and Mackintosh (1983)

Language changes are passed down from generation to generation by being immersed in culture

Passing on information occurs via imitation and teaching; through socialisation and engagement with others in society. This is known as cultural learning. Cultural transmission occurs when groups perceive a benefit in change, such as status, assimilation, or promotion.

To look for in a text: CONTEXT, SEMANTICS

Shifts in values, cultures, contexts

Stories and idioms

Quirky phrases or lexis

Random Fluctuation Theory by Charles Hockett

Language is unstable and constantly changing which results in random errors and events, therefore causing more change

Random fluctuation can occur particularly in accents where people adopt a new pronunciation as it sounds ‘better’ or ‘aesthetically pleasing’. People can adopt these random fluctuations when they seem more desirable.

To look for in a text: PHONOLOGY, ORTHOGRAPHY, LEXIS, SEMANTICS

Phonetically influenced spelling

Seemingly random lexis used in a context that appears to mean something other than denotation

Narrowed or broadened semantic change

Substratum Theory from various 60s/70s studies, namely William Labov

Language change is caused by interaction and contact with other languages

Links language change to the spread and globalisation of language as one variety of English is influenced by another through contact. For example, the word ‘like’ denotes comparison, however, it has spread throughout the English-speaking world as a filler in spoken discourse. Second-generation English speakers alter pronunciation, as seen in William Lablov’s study of Jewish communities in New York which has given way to create the distinctive New York accent. Loan words such as ‘croissant’ from French, or Americanisms such as ‘my bad’ are also examples of substratum theory in action.

To look for in a text: LEXIS, PHONOLOGY

Borrowings and loan words

Changes in pronunciation

Americanisms

Theory of Lexical Gaps is an offshoot of Michael Halliday’s Functional Theory

A fully present word developed in one language that does not exist in another

The theory suggests that certain lexis emerges as a result of its absence in the current language. Due to the finite number of letters in English, some permutations and combinations of letters can be formed into coherent words while others simply do not make sense. Words have to be borrowed from other languages to fill these gaps. These gaps exist due to synonymy blocking (words that could exist aren’t used because of an existing synonym, eg stealer from root word steal is not used because thief exists) and homonymy blocking (words that could exist aren’t used because of an existing homonym, eg liver being someone who lives is not used because the liver organ exists).

To look for in a text: LEXIS, MORPHOLOGY

Synonymy and homonomy blocking (e.g stealer instead of thief in old texts)

Convoluted collocations to describe something that needs a word / semantic gaps (eg a parent who has lost their child)

Neologisms that express something people cannot find a word for

Irregular inflections on words that are now not used due to synonyms for these words

Loans words and borrowing (eg cliche comes from French as it has no English equivalent)

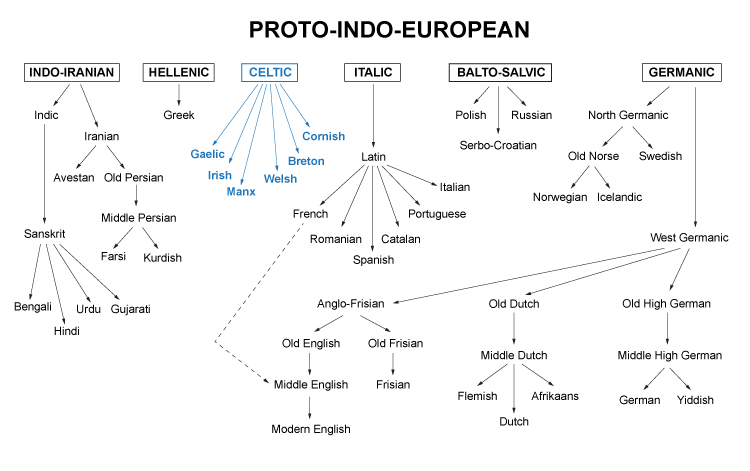

Tree Model

Language change in relation to a family tree; older generations are further up and newer generations branch out

This model is a more theoretical model rather than one that can be observed. It is part of historical linguistics.

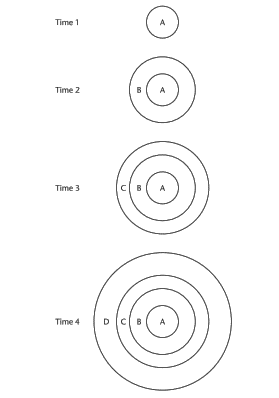

Wave Model

Features spread from their region of origin, affecting a gradually expanding cluster of dialects

Slang or neologisms that are created in one location may spread, however, the farther from the point of origin, the less recognisable or significant the ‘ripple effect’ of the ‘wave’ will be.

To look for in a text: N-GRAM, CONTEXT, LEXIS

Present-day English — internet language

The shape of an n-gram to see if there was historically a moment of contact

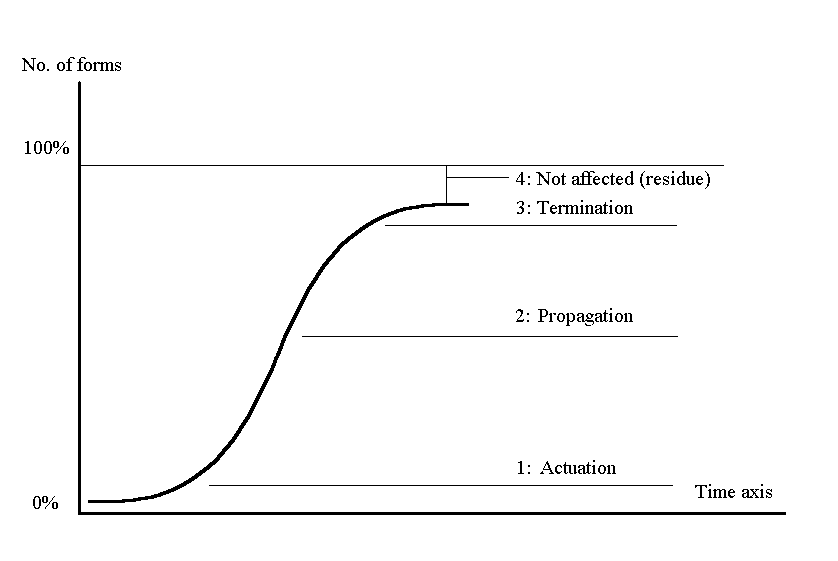

S-Curve Model

A change that starts slowly, picks up speed and proceeds rapidly

New and coming words accelerate in use before settling back down and becoming the dominant synonym for a word. Older forms may be used in specific contexts but be largely out of use.

To look for in a text: N-GRAM, CONTEXT

The shape of the n-gram and the moment of initial growth

Jean Aitchison’s Processes

Potential — there is an internal weakness or external pressure for a particular change

Diffusion — the change starts to spread through the population

Implementation — people start using the variant; it is incorporated into people’s idiolect/group/local languages

Codification Model — written down and subsequently put into the dictionary and accepted officially

Hegel’s Dialectics Theory

The study of dialectics comes from Plato. He demonstrates with Socrates as his model arguing against another person, unnamed, in a back-and-forth debate. This back-and-forth debate leads to the evolution of more sophisticated views in order to battle the opposition.

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (1770-1831) was a German philosopher who developed his own dialectics theory after Plato. He was critical of Plato’s dialectics model, believing that it never went beyond skepticism and nothingness; it only generates approximate truths. His theory relies on a contradictory process between opposing sides; while Plato’s model was between people, Hegel’s model was on the subject he discusses and how different sides oppose each other.

There are three major concepts to Hegelian dialectics:

thesis

antithesis

synthesis

The thesis is contradicted by an antithesis which is then resolved at a higher level of truth (synthesis). As two ideas oppose each other, it forms a new idea as a compromise between the two opposing ideas.

ESSAY WRITING

Framework | TLC POMP SSSS |

|---|---|

Typography | Medial s, ligatures, justification of alignment through hyphens/apostrophes, exclamation marks imply excitement, drop cap |

Lexis | Obsolete, archaic, old-fashioned, dialectical, loanword, borrowing, coinage, connotations, semantic changes |

Context | Period of language development: OE, ME, EME, LME, quality of printing presses over centuries, standardisation, gender/class issues, theories of language change, Aitchison’s processes of language change, Americanisms vs British synonyms, audience class and gender |

Phonology | Hyphens and apostrophes to mark phonetically based spelling, alliteration for speed or emphasis, harsh consonants to give extra emphasis, rhythm, rhyme, assonance, sibilance |

Orthography | Capitalisation, hyphenation (pre-compounding), spelling, interchangeable letters (i/y, u/v) |

Morphology | Inflections/morphemes |

Punctuation | full stops and where they are located, semi-colons, virgules |

Syntax | Collocations, inversion of negatives |

Semantics | Semantic change, shift from noun form to adjective form and vice versa (conversion), pejoration/amelioration over time, diachronic language change, synchronic language change, collocations over time |

Structure | Sentence length, semi-colons, virgules (/), colons, periods, commas, listing, repetition |

Significant events | The Great Vowel Shift (1400-1700), the introduction of the printing press (1476), the Renaissance (1500-1600), the King James Bible (1611), Samuel Johnson dictionary (1755), Robert Lowth grammar guide (1762) |

Extra Analysis | |

Archaisms | archaic inflections ‘whilest’, interchangeable letters, archaic syntax/word order, archaic lexis, Latinate, French words in the English language after 1066, neologisms, semantic change, non-standard spelling, inconsistent spelling, irregular capitalisation, extra ‘e’ on the end or doubling of vowels |

Register | is it formal? Is it informal? |

Imagery | metaphors, hyperbole, simile, personification, oxymoron, etc |

Spontaneous speech | ellipsis, phatic expressions, deixis, clipping, discourse markers, false starts, elision, pause, fillers, unintentional repetition, tag questions |

Word classes | nouns, adjectives, pronouns, verbs, adverbsintensifierssimple, compound, and complex sentence typesinterrogative, declarative, exclamatory, and imperative sentence functionsparenthesis |

CIE A2 Level English: Language Change

Foreword: these notes were made in collaboration with a friend due to the complexity of the topic; I only take half of the ownership of these notes. By sharing this, I do hope people find the topic less daunting than it seems.

HISTORY OF LANGUAGE CHANGE

Old English (400 – 1150)

YEAR | STATE OF BRITAIN | LANGUAGE |

|---|---|---|

Pre 5th century | Occupied by original inhabitants of the British Isles | Celtic languages |

410 | Romans leave Britain after invading 3 times | Latin |

700 | Vikings invade | Old English/Anglo-Saxon (parts of the Scandinavian language became integrated eg family, animals) |

1066 | Norman conquest | Latin (church, learning) |

1362 (Middle English) | ME becomes the official language of the court | Middle English |

Middle English (1150 – 1450)

Anglo-Norman became the standard literary language and eventually, the language of the court in this time period.

Sound system had undergone dramatic changes but the spelling had barely changed. The French scribes updated the spelling of many English sounds and English gained 10,000 new words in this period.

New grammatical constructions came about, especially with the merging of Old English and Old French lexis. The word ‘unreasonable’ came from the Old English prefix ‘un’ and the Old French word ‘raisonable’.

FEATURES OF MIDDLE ENGLISH:

Simple grammar

Inflections disappeared and relatively uninflected (all plurals ended in -s, -es and -en)

Reflected shared languages

1000s of Latin words replaced Old English

Heavily influenced by French lexis (namely legal, religious and administrative lexis)

Vowels became shorter, would degrade into an indeterminate sound

No standardised form of spelling

After the Black Death (also known as the Black Plague) in 1348–50, the remaining working class grew in importance. English regained its status as Anglo-Norman became less used.

By the 14th century, Oxford University decreed that all students must speak English, as well as French. However, by the 15th century, the language took on 4 different dialects: Northern, East Midland, West Midland, and Southern, including a small sub-dialect of Kentish.

The East Midland and London dialects grew in prominence, particularly after William Caxton’s introduction of the printing press to England where he wrote in the East Midland dialects. The dialect also managed to survive due to:

geography — it had elements from both North and South dialects and was seen as a compromise between them

economic influence — the region had the largest and wealthiest people; agriculturally rich out of all the regions

academic influence — Oxford and Cambridge (which conducted their education in East Midland and London dialects) were of high intellectual influence

London as the capital — London was the commercial, political, legal, and social capital of the country

Linguistic Features of Archaic Texts

Lexis | words that are often no longer used e.g thee, thou, bacchanalia; could show archaic views on gender compared to modern day such as taboo terms |

|---|---|

Syntax | sentence structure that is not considered ‘correct’ now e.g Sometime too hot the eye of heaven shines |

Inflections | affixation at the beginning or end of words is no longer used e.g -eth (seemeth) or -est (whilest) |

Interchangeable letters | u and v were both used for the ‘u’ sound of words e.g Vnkle → uncle; also occurred to y & i and s and the medial s (ſ) |

Latinate lexis | words borrowed from Latin; usually have multiple syllables and their meanings tend to be more broad, abstract, or scientific e.g Anglo-Saxon ‘see’ vs Latinate ‘perceive’ |

French lexis | words borrowed from French, many related to politics e.g plebiscite, sovereignty, coup d’etat |

Non-standard spelling | some lexis would be spelled based on phonology or the writer’s knowledge e.g ‘fixt’ vs ‘fixed’ |

Inconsistent spelling | words spelled differently in the same text |

Pronunciation | doubling of vowels, an extra ‘e’ on the ends of words, double consonants to make long vowel sounds |

Early Modern English (1470 – 1800)

1400-1700s: Great Vowel shift

Pronunciation had shifted however spelling stayed the same due to the use of the same printing presses

1476: William Caxton brought the printing press to England

Greek and Latin texts were translated to English

Standardisation of English began

Punctuation and syntax features:

Virgule (/) or oblique stroke was everywhere

Full stop at different heights

Capitalisation was random with none for proper nouns

Colons were very common and had a broad range of use

Semi-colons were everywhere

Sentences could be 20+ lines long with a wide use of ‘and’ and ‘then’ coordinates

No paragraphs

1500s: Large use of printing in the 16th century

Books were luxury items and took weeks to months to create

Literacy rates exploded and prompted a new social dilemma

Double vowels (soon) and consonants (sitting) became widely used

Silent e used to mark the long length of a vowel sound (name)

All words that an author deemed important were capitalised

1500-1660: The Renaissance

Renewed respect for Classical literature and the arts

influence in Greek and Latin

Neologisms usually taken from Greek and Latin

Huge expansion of travel trade and colonialism accounted for large imports of foreign words, especially European

10,000-12,000 new words appeared in the English language

Following French practices, apostrophes were used when a vowel was omitted (lov’d)

u+v, i+j, y+i had no fixed phonetic values, used interchangeably

‘e‘ still found at the end of words

spelling is still irregular

Most shifts had occurred by the end of the Renaissance

1530-1600: The Reformation

Puritan moral beliefs and science heavily influenced texts and behaviours

1564-1616: Shakespeare

Many Shakespearean coinages entered the English Language such as eventful, laughable

John Hart was a spelling reformer who tried to introduce books on orthography and English spelling

John Hart also tried to establish capitalisation rules by saying anything deemed important by the writer should be capitalised

1611: The King James Bible

The KJB brought a standard version of the Bible to all people, many other versions of the Bible varied greatly

Much more conservative style of writing than Shakespeare

Contained grammar, forms and construction that were out of use elsewhere

1660-1688: The Restoration

Expansion in colonial trade saw more contact language

Revival of drama and literature, and new scientific discoveries, philosophical concepts and social and economic conditions

1755: Samuel Johnson’s dictionary

Standardisation became more prevalent

Spelling have begun to be codified

Apostrophes were eventually used as we do today

Paragraphs were in use

1762: Robert Lowth’s ‘Short Introduction to English Grammar’

Grammar standardisation; had 200 pages of arbitrary idiosyncratic rules on which grammatical forms should be avoided and encouraged

“two negatives in English destroy one another, or are equivalent to an affirmative”

“never put a preposition at the end of a sentence”

Late Modern English (1800 - Present)

Most prominent change was an expansion of lexis due to industrial and social developments, and colonialism. However, with changes came reactionaries.

This was a result of the Industrial Revolution (1760-1840) in which new words were introduced to describe new technology. Therefore, the language change was mostly lexical, making it similar to EME in terms of grammar and spelling rules. Noah Webster published his dictionary (1828), which differentiated American English from British English.

American English removes ‘u’ after ‘o’ (color vs colour), removes an ‘l’ in verbs (traveling vs travelling), switches s/c, z/s and a/e (defense vs defence, realize vs realise, and gray vs grey) and adds an ‘l’ at the end of words (fulfill vs fulfil).

The internet also brought forth a wide new range of jargon and the rapid spread of new lexis.

However, prescriptivists believed in following the rules of Latin as it was the historical language of the Bible, the law and courts, the classics, and of educated society;

Latin was seen as a pure and authoritative language with strict, unchanging rules unlike English. Although, the language has remained dead as it is not the language now for common communication

ESSAY APPLICATION:

Spread of literacy and mass production of printed word solidified standardisation and literacy as everyone had access to written English

American English was becoming a language of its own with distinguished orthographical spelling

Conversations and lexis shortened - abbreviations, telescoping, clipping

Hashtags and emojis reduce the number of words used

Grammatical rules have been discarded in texting due to the informal register necessary between friends

English has spread and become a global form of communication - many cultures have their own dialects and forms.

LANGUAGE CHANGE VIEWS

Reasons for Language Change

individuals — Chaucer, Shakespeare

Chaucer was one of the first people to write in English rather than French after the Norman invasion. His Canterbury Tales in the late 14th century was written in English Vernacular (the English spoken by the people in the East Midlands, which then became a prominent dialect) and his works attributed to the creation of iambic pentameter and the rhyme royal

Shakespeare is noted to have brought many new lexis to the English language, such as laughable and lacklustre, as well as many idioms. such as ‘seen better days’ and ‘slept not one wink’

technology — the printing press, typewriters, the internet; David Crystal believed that language change occurs due to these technological advancements

society — cultural changes and shifts

conscious change — change from above such as dominating social positions

unconscious change — change from below, those adapting language according to their own social needs, such as dialects

political correctness;

refrain from causing emotional harm (pragmatics)

assimilation into society

taboo

used for comedic effect

convergence or divergence

used as a filler or to show pain and displeasure

negative views

too much on TV

foreign influence i.e through trade, film, and music

new scientific discoveries and/or inventions

travel, trade, and colonisation — lexical changes as people adopt the other language for better customer service; accommodation theory

loanwords/borrowing

affixation

compounding

blending

conversion

shortening/abbreviation

acronyms

initialism

broadening/generalisation

globalisation — English becoming the language of trade and business

internal factors — language changes within itself

Prescriptivism vs Descriptivism

Prescriptivism: dictate how language should be used; believe in a more ‘correct’ form of English; refrains from change; reactionary

Lynne Truss: ‘Proper punctuation is both the sign and the cause of clear thinking’, ‘To those who care about punctuation, a sentence such as “Thank God its Friday” rouses feelings not only of despair but of violence’

John Humphrys (declinist prescriptivist): ‘They are destroying it: pillaging our punctuation; savaging our sentences; raping our vocabulary. And they must be stopped!’

Kathy August: ‘Slang doesn’t really give the right impression of a person’

S.K Ratcliffe: ‘the language is going to pieces before our eyes, especially under the influence of the Debased dialect of the cockney’

Robert Lowthe: ‘Our language is extremely imperfect, … it offends against every part of grammar.’

John Walker, author of A Critical Pronouncing Dictionary (1791): people with Scottish or Irish accents, Londoners with a Cockney accent sounded ‘a thousand times more offensive and disgusting’

Descriptivism: accept language change is inevitable and accept change; revolutionary

David Crystal: ‘no two high tides are the same’, ‘no changes are for the better; nor for the worst; they’re just changes’

Oliver Kamm: ‘prescriptivists want a ‘golden society’ that never existed’, ‘English is a river; it flows through many tributaries’

James Milroy: ‘There was no Golden Age’

Julie Blake: ‘to attempt to fix language is laughable… a futile attempt to defy… human nature’

‘the ideal campaign of a worthy dictionary was descriptive, not prescriptive … like the English language, [it would] live and breathe and change.’

John Ayto (lexicographer): ‘Words are a mirror of their times.’

Peter Trudgill: ‘Languages are self-regulating systems which can be left to take care of themselves’

Jean Aitchison’s Three Metaphors

Crumbling castle view - depicts the English language as an old building that must be preserved

Implies that there was once a peak of perfection in English (Golden Age) but no one can say when this date would have even been.

John Simon: “language should be treated like parks… available for properly respectful use but not for defacement or destruction”

If one part of the castle breaks, the rest falls if it is not immediately fixed

Infectious disease view - people catch language changes from those around them and must fight these diseases

In reality, people pick up changes because they want to

People change to adapt to social groups, such as jocks in a Detroit school copying standard adult speech while burnouts moved away from it.

Damp spoon syndrome view - laziness and sloppiness cause most language change

Omission of syllables at the end of words allows speech to speed up

Efficiency of speech

Dennis Freeborn’s Three Views

Incorrectness View — all accents are incorrect compared to Standard English and Received Pronunciation

Popularity of certain accents originates in fashion and convention but is not ‘correct’

Ugliness View — accents that aren’t Received Pronunciation don’t sound nice; they have negative connotations and stereotypes

This is commonly given to the Scouse accent associated with Liverpool in England; also known as Liverpool English or Merseyside English

Northern and Central Scouse sounds harsh, nasal, and fast

Southern Scouse is more slow, soft, and dark

often found in poorer urban areas

Impreciseness View — some accents are just ‘lazy’ and ‘sloppy’

Estuary English is a dialect where sounds are either ommitted or changed

The Inkhorn Controversy: a discussion over the use of foreign words in the English language

By the 15th and 16th centuries, between 10,000 to 25,000 new words were found in the English language, largely originating from Latin and Greek roots. These words became known as ‘inkhorn terms’ or ‘inkhornisms’.

Those who supported the inkhorns were:

Thomas Elyot

Georgie Pettie; ’for what word can be more plaine then this word plaine, and yet what can come more neere to Latine?’

Ben Jonson; ‘Yet we must adventure; for things at first hard and rough are by use made tender and gentle.’

Those who were against inkhornisms were:

Thomas Wilson; ‘if some of their mothers were alive, thei were not able to tell what they say’

John Cheke; ‘our tung shold be written cleane and pure, vnmixt and vnmangeled with borowing of other tunges’

THEORIES AND THEORISTS

Functional Theory by Michael Halliday

Language changes to suit the needs of the users, who need words to describe new ideas and objects, and ways to express themselves and their social identity

According to the functional theory, lexis is not actively discarded, but rather evolves until it is obsolete.

To look for in a text: LEXIS

Neologisms and coinage

Abbreviations, contractions, clippings, back-formations

Archaisms and obsolete lexis

Colloquialisms and slang

Jargon

Communication Accommodation Theory by Howard Giles

Like the Functional Theory, speakers change the way they speak and the way they utilise language depending on who they are speaking to.

Giles believed in the idea of ‘convergence’, where people make their language more like the person they are talking to in order to accommodate the other speaker — this makes the receiver feel more appreciative and valued. This includes speaking slower, using the other person’s local slang, or diluting our accents.

Case Study: Matha’s Vineyard by William Labov (1963)

William Labov was studying phonological variation, particularly in diphthongs. He conducted his study on an island called Martha’s Vineyard off the northeast coast of America.

Labov interviewed 69 different people people of varying age, race, and social groups. The questions he used subconsciously urged the participants to use words which contained the desired vowels he intended to study. Some interview questions he used were:

“When we speak of the right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, what does right mean? … Is it in writing?”

“If a man is successful at a job he doesn’t like, would you still say he was a successful man?”

His results found that phonological variation was based on social loyalty. Those who intended to stay on the island spoke with a more centralised accent that was farther from mainland pronunciations while those who wished to leave spoke with less centralisation with the intention to go to the mainland.

Cultural Transmission Theory from various theorists such as Hartl and Clark (1997), Bandura (1977), and Mackintosh (1983)

Language changes are passed down from generation to generation by being immersed in culture

Passing on information occurs via imitation and teaching; through socialisation and engagement with others in society. This is known as cultural learning. Cultural transmission occurs when groups perceive a benefit in change, such as status, assimilation, or promotion.

To look for in a text: CONTEXT, SEMANTICS

Shifts in values, cultures, contexts

Stories and idioms

Quirky phrases or lexis

Random Fluctuation Theory by Charles Hockett

Language is unstable and constantly changing which results in random errors and events, therefore causing more change

Random fluctuation can occur particularly in accents where people adopt a new pronunciation as it sounds ‘better’ or ‘aesthetically pleasing’. People can adopt these random fluctuations when they seem more desirable.

To look for in a text: PHONOLOGY, ORTHOGRAPHY, LEXIS, SEMANTICS

Phonetically influenced spelling

Seemingly random lexis used in a context that appears to mean something other than denotation

Narrowed or broadened semantic change

Substratum Theory from various 60s/70s studies, namely William Labov

Language change is caused by interaction and contact with other languages

Links language change to the spread and globalisation of language as one variety of English is influenced by another through contact. For example, the word ‘like’ denotes comparison, however, it has spread throughout the English-speaking world as a filler in spoken discourse. Second-generation English speakers alter pronunciation, as seen in William Lablov’s study of Jewish communities in New York which has given way to create the distinctive New York accent. Loan words such as ‘croissant’ from French, or Americanisms such as ‘my bad’ are also examples of substratum theory in action.

To look for in a text: LEXIS, PHONOLOGY

Borrowings and loan words

Changes in pronunciation

Americanisms

Theory of Lexical Gaps is an offshoot of Michael Halliday’s Functional Theory

A fully present word developed in one language that does not exist in another

The theory suggests that certain lexis emerges as a result of its absence in the current language. Due to the finite number of letters in English, some permutations and combinations of letters can be formed into coherent words while others simply do not make sense. Words have to be borrowed from other languages to fill these gaps. These gaps exist due to synonymy blocking (words that could exist aren’t used because of an existing synonym, eg stealer from root word steal is not used because thief exists) and homonymy blocking (words that could exist aren’t used because of an existing homonym, eg liver being someone who lives is not used because the liver organ exists).

To look for in a text: LEXIS, MORPHOLOGY

Synonymy and homonomy blocking (e.g stealer instead of thief in old texts)

Convoluted collocations to describe something that needs a word / semantic gaps (eg a parent who has lost their child)

Neologisms that express something people cannot find a word for

Irregular inflections on words that are now not used due to synonyms for these words

Loans words and borrowing (eg cliche comes from French as it has no English equivalent)

Tree Model

Language change in relation to a family tree; older generations are further up and newer generations branch out

This model is a more theoretical model rather than one that can be observed. It is part of historical linguistics.

Wave Model

Features spread from their region of origin, affecting a gradually expanding cluster of dialects

Slang or neologisms that are created in one location may spread, however, the farther from the point of origin, the less recognisable or significant the ‘ripple effect’ of the ‘wave’ will be.

To look for in a text: N-GRAM, CONTEXT, LEXIS

Present-day English — internet language

The shape of an n-gram to see if there was historically a moment of contact

S-Curve Model

A change that starts slowly, picks up speed and proceeds rapidly

New and coming words accelerate in use before settling back down and becoming the dominant synonym for a word. Older forms may be used in specific contexts but be largely out of use.

To look for in a text: N-GRAM, CONTEXT

The shape of the n-gram and the moment of initial growth

Jean Aitchison’s Processes

Potential — there is an internal weakness or external pressure for a particular change

Diffusion — the change starts to spread through the population

Implementation — people start using the variant; it is incorporated into people’s idiolect/group/local languages

Codification Model — written down and subsequently put into the dictionary and accepted officially

Hegel’s Dialectics Theory

The study of dialectics comes from Plato. He demonstrates with Socrates as his model arguing against another person, unnamed, in a back-and-forth debate. This back-and-forth debate leads to the evolution of more sophisticated views in order to battle the opposition.

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (1770-1831) was a German philosopher who developed his own dialectics theory after Plato. He was critical of Plato’s dialectics model, believing that it never went beyond skepticism and nothingness; it only generates approximate truths. His theory relies on a contradictory process between opposing sides; while Plato’s model was between people, Hegel’s model was on the subject he discusses and how different sides oppose each other.

There are three major concepts to Hegelian dialectics:

thesis

antithesis

synthesis

The thesis is contradicted by an antithesis which is then resolved at a higher level of truth (synthesis). As two ideas oppose each other, it forms a new idea as a compromise between the two opposing ideas.

ESSAY WRITING

Framework | TLC POMP SSSS |

|---|---|

Typography | Medial s, ligatures, justification of alignment through hyphens/apostrophes, exclamation marks imply excitement, drop cap |

Lexis | Obsolete, archaic, old-fashioned, dialectical, loanword, borrowing, coinage, connotations, semantic changes |

Context | Period of language development: OE, ME, EME, LME, quality of printing presses over centuries, standardisation, gender/class issues, theories of language change, Aitchison’s processes of language change, Americanisms vs British synonyms, audience class and gender |

Phonology | Hyphens and apostrophes to mark phonetically based spelling, alliteration for speed or emphasis, harsh consonants to give extra emphasis, rhythm, rhyme, assonance, sibilance |

Orthography | Capitalisation, hyphenation (pre-compounding), spelling, interchangeable letters (i/y, u/v) |

Morphology | Inflections/morphemes |

Punctuation | full stops and where they are located, semi-colons, virgules |

Syntax | Collocations, inversion of negatives |

Semantics | Semantic change, shift from noun form to adjective form and vice versa (conversion), pejoration/amelioration over time, diachronic language change, synchronic language change, collocations over time |

Structure | Sentence length, semi-colons, virgules (/), colons, periods, commas, listing, repetition |

Significant events | The Great Vowel Shift (1400-1700), the introduction of the printing press (1476), the Renaissance (1500-1600), the King James Bible (1611), Samuel Johnson dictionary (1755), Robert Lowth grammar guide (1762) |

Extra Analysis | |

Archaisms | archaic inflections ‘whilest’, interchangeable letters, archaic syntax/word order, archaic lexis, Latinate, French words in the English language after 1066, neologisms, semantic change, non-standard spelling, inconsistent spelling, irregular capitalisation, extra ‘e’ on the end or doubling of vowels |

Register | is it formal? Is it informal? |

Imagery | metaphors, hyperbole, simile, personification, oxymoron, etc |

Spontaneous speech | ellipsis, phatic expressions, deixis, clipping, discourse markers, false starts, elision, pause, fillers, unintentional repetition, tag questions |

Word classes | nouns, adjectives, pronouns, verbs, adverbsintensifierssimple, compound, and complex sentence typesinterrogative, declarative, exclamatory, and imperative sentence functionsparenthesis |

Knowt

Knowt