AP English Language & Composition Ultimate Guide

Unit 1: Rhetoric and the Elements of Style

What is Rhetoric?

When we talk about rhetoric, we are talking about language as a means of persuasion.

More specifically, rhetoric refers to the strategies an author uses to impact an audience and persuade them of a specific idea.

The author uses X, which accomplishes Y and persuades the audience of Z.

X: This variable represents the specific rhetorical strategies an author uses.

An author might use a metaphor or a simile, or they might use formal diction or very casual diction.

Y: This variable refers to how the rhetorical strategies in the text impact the audience.

A catchy title is a rhetorical strategy designed to capture the audience’s attention.

Audience: Audience refers to the individuals the speaker is trying to persuade.

More generally, it is the people who read (or hear, in the case of a speech) a text.

Z: This variable represents a text’s theme or argument.

This is a developed idea an author wants to convey.

In other words, the theme is what the author is trying to persuade the audience of.

Rhetorical Strategies

Rhetorical strategies describe how an author uses language to construct a text.

“Rhetorical strategies” is a broad term, including basic diction and syntax, as well as more complicated uses of figurative language.

Diction

The diction questions you’ll see on the test will ask you to evaluate why an author’s choice of words is particularly effective, apt, or clear.

Often, the test will ask you to consider what style and/or tone an author’s use of diction develops.

Denotation and Connotation

Denotation refers to a word’s primary or literal significance, while connotation refers to the vast range of other meanings that a word suggests.

Context (and at times, author’s intent) determines which connotations may be appropriate for a word.

An author will carefully pick a particular word for its connotations, knowing or hoping a reader will make an additional inference as a result.

For example: I am looking at the sky.

The denotation of the underlined word should be as clear as a cloudless sky (the space, often blue, above the Earth’s surface).

Syntax

Syntax is the ordering of words in a sentence; it describes sentence structure.

Syntax in rhetorical strategies refers to the arrangement of words and phrases to achieve a desired effect.

It is used strategically by speakers or writers to convey meaning and emotion, persuade an audience, emphasize key points, create a sense of cohesion between ideas, and craft arguments more effectively.

For example:

Never was anything so gallant, so well outfitted, so brilliant, and so finely disposed as the two armies. The trumpets, fifes, reeds, drums, and cannon made such harmony as never was heard in Hell.

The first sentence depicts a beautiful battle.

The second begins similarly, but its phrases are structured to maximize the surprise at the end.

Being the last item on a list of military musical instruments, the cannons are expected to fit well.

It doesn't, but a new setup with the words "such harmony as never been heard..." distracts us before we can register our amazement.

We expect harmony to be beautiful and start to give the concluding word (Earth? Heaven?) until Voltaire surprises us with Hell.

Figurative Language

Figurative language is strictly defined as speech or writing that departs from literal meaning to achieve a special effect or meaning.

With malice toward none, with charity for all, with firmness in the right as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in, to bind up the nation’s wounds, to care for him who shall have borne the battle and for his widow

and his orphan, to do all which may achieve and cherish a just and lasting peace among ourselves and with all nations.

Do we literally interpret "to bind up the nation's wounds"? Certainly not.

Lincoln has personalized our country to make the suffering of individuals understandable to all of us.

What about "he who shall have borne the battle"? Lincoln's use of "his widow and his orphan" clarifies that "shall have borne the battle" meaning "shall have perished in battle."

Instead of talking about this group's suffering, Lincoln talks about individual sacrifice, which he knows would touch his audience.

Imagery

Imagery in figurative language is when an author uses vivid or metaphorical language to create a mental image that helps readers visualize what's being described.

Some examples of imagery include metaphors, similes, personification, and onomatopoeia.

Hyperbole

Hyperbole is overstatement or exaggeration; it is the use of figurative language that significantly exaggerates the facts for effect.

In many instances, but certainly not all, hyperbole is employed for comic effect.

For example: If you use too much figurative language in your essays, the AP readers will crucify you!

Clearly, this statement is a gross exaggeration; while the readers may give you a poor grade if you use figurative language that doesn’t suit the purposes of your essay, they will not kill you.

Understatement

Understatement is figurative language that presents the facts in a way that makes them appear much less significant than they really are.

Understatement is almost always used for comic effect.

For example:

After dinner, they came and took into custody Doctor Pangloss and his pupil Candide, the one for speaking his mind and the other for appearing to approve what he heard. They were

conducted to separate apartments, which were extremely cool and where they were never bothered by the sun.

Taking the last statement literally will lead you wrong.

The understatement in this example ("They were brought to separate apartments, which were extremely cool and where they were never bothered by the sun") implies that the poor men were dumped into horrifyingly gloomy, dank, and frigid jail cells.

Simile - A simile is a comparison between two unlike objects, in which the two parts are connected with a term such as like or as.

For example: The birds are like black arrows flying across the sky.

Metaphor - A metaphor is a simile without a connecting term such as like or as.

For example: The birds are black arrows flying across the sky.

Birds are not arrows, but the commonalities (both are long and sleek, and they travel swiftly through the air—and both have feathers) allow us to easily grasp the image.

Extended Metaphor - An extended metaphor is precisely what it sounds like—it is a metaphor that lasts for longer than just one phrase or sentence.

For example:

During the time I have voyaged on this ship, I have avoided the cabin; rather, I have remained on deck, battered by wind and rain, but able to see moonlight on the water. I do not wish to go below decks now.

As strange as it may appear, this passage is not about maritime navigation.

The writer uses figurative language to deepen the metaphor of the ship's journey, which represents the passage of life.

On deck, you're exposed to the weather but can see beautiful sights.

The cabin is safe but not very exciting.

Having made the tough, hazardous, but gratifying option of staying on deck, it would be a personal failure to wish for the cabin's safety, comfort, and limited horizons later in life.

Symbolism - A symbol is a concrete object that represents an abstract idea.

For example: The Christian soldiers paused to remember the lamb.

In this case, the lamb is a symbol.

The lamb is a concrete object that represents an abstract idea.

In this case, the lamb symbolizes the legacy of Jesus Christ.

Personification

Personification is the figurative device in which inanimate objects or concepts are given the thoughts, feelings, or actions of a human.

It can enhance our emotional response because we usually attribute more emotional significance to other humans than to things or concepts.

For example:

He had been wrestling with lethargy for days, and every time that he thought that he was close to victory, his adversary escaped his hold.

This figurative wrestling bout, in which lethargy is personified as the opponent to the author of this text, brings the conflict to life—human life.

If you don't accept this, consider the alternative: he attempted to quit being lethargic but failed.

This doesn't sound too lively.

Anthropomorphism occurs when non-human objects are given the physical shape of a human, e.g., the legs of a table, the face of a clock, the arms of a tree.

Circumlocution and Euphemism

Circumlocation is a form of communication in which the speaker's meaning is not directly expressed but implied, often through metaphors or other forms of figurative language.

It can be used to build suspense, hide sensitive information, or simply express emotions and feelings more effectively than literal words can do.

A euphemism is a word or words that are used to avoid employing an unpleasant or offensive term.

Paradox

A paradox contains two elements which cannot both be true at the same time (although usually each one could be true on its own).

The classic example is the Cretan Liar Paradox, attributed to the sixth- century BCE philosopher and poet Epimenides. He was from Crete, and his famous paradox says, “All Cretans are liars.”

Rhetorical Question

A rhetorical question is a question whose answer is obvious; these types of questions do not need to be answered—and usually aren’t.

Rhetorical questions attempt to prove something without actually presenting an argument; sometimes they’re used as a form of irony, in which something is stated, but its opposite is meant.

For example:

Given how cheap the most fattening foods are, is it any wonder obesity is on the rise? (no irony)

Aren’t AP Exams great fun? (with irony)

Irony and Satire

Irony is a figure of speech in which words are used to convey the opposite of their literal meaning.

It can be used to make a point, add humor or emphasize something.

Verbal Irony

Verbal irony refers to the process of stating something but meaning the opposite of what is stated.

In cases of verbal irony, the audience can anticipate the dialogue or specific language used in a text.

The author may use a common saying, situation, or emotional experience to build up the audience’s expectation.

For example, an author may describe an experience while shopping. When the author enters the store, the salesperson says, “Hello, how can you help me?” This would be ironic because the expectation is that the salesperson would say the opposite, “How can I help you?”

Sarcasm is simply verbal irony used with the intent to injure.

It’s often impossible to discern between irony and sarcasm, and, more often than not, sarcasm is in the mind of the beholder.

For example, when someone says "That's great" but they mean something completely different.

Situational Irony refers to a circumstance that runs contrary to what was expected.

For example: Suppose you live in Seattle during the rainy season and plan a vacation to sunny Phoenix. While you are in Phoenix, it rains every day there, but is sunny the entire week in Seattle.

Satire - something is portrayed in a way that’s deliberately distorted to achieve comic effect.

Implicit in most satire is the author’s desire to critique what is being mocked.

Example: An example of satire would be Jonathan Swift's "A Modest Proposal". In this essay, Swift suggests the Irish people should eat their own children in order to solve poverty and hunger. This proposal was obviously not meant to be taken seriously - it was intended as a way for Swift to mock the British government's indifference towards its citizens' plight.

The following terms are similar, but not identical. Know the differences.

Satire: A social or political criticism that relies heavily on irony, sarcasm, and often humor

Parody: Imitation for comic effect

Lampoon: Sharp ridicule of the behavior or character of a person or institution

Caricature: A ludicrous exaggeration of the defects of persons or things

Style, Tone, and Mood

Style is the general manner of expression used in a text.

It describes how the author uses language to get his or her point across (e.g., pedantic, scientific, or emotive).

Tone describes the speaker’s attitude toward the subject.

Tone describes how the author seems to be feeling (e.g., optimistic, ironic, or playful).

Mood describes how the text makes the audience feel.

For example:

Our left fielder couldn’t hit the floor if he fell out of bed! After striking out twice (once with the bases loaded!), he grounded into a double-play. My grandmother runs faster than he does! In the eighth inning, he misjudged a routine fly ball, which brought in the winning run. What a jerk! Why didn’t the club

trade him last week when it was still possible? What’s wrong with you guys?

The style is simple, direct, unsophisticated, truculent, and even crass.

The tone is angry, brash, emotional, and even aggressive.

The mood is stressed and concerned.

Pay close attention to the final sentence: The speaker accuses the audience directly with “you,” which could make the audience feel guilty, defensive, or angry.

Classical Appeals

Logos is an appeal to reason and logic.

An argument that uses logos to persuade needs to provide things like objective evidence, hard facts, statistics, or logical strategies such as cause and effect to back up its claim.

Ethos is an appeal to the speaker’s credibility—whether he or she is to be believed on the basis of his or her character and expertise.

Pathos is an appeal to the emotions, values, or desires of the audience.

Unit 2: Basic Rhetorical Modes

Rhetorical Modes

Rhetorical modes are ways of using language that are intended to have an effect on the audience.

Classification

Aristotle liked to classify, and he did so quite often. Some of his classifications have stood the test of time, including the one below, which is the beginning of Part 6 of an essay entitled “Categories.”

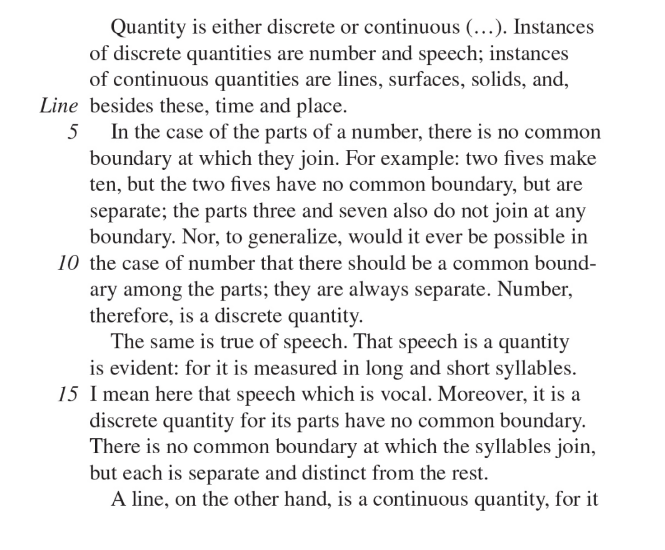

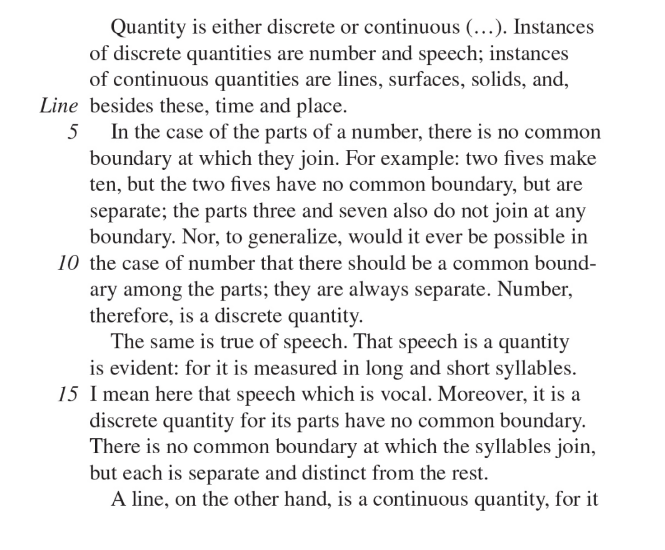

Here, Aristotle’s division of quantity into two categories (discrete and continuous) makes sense.

The examples that he uses to illustrate the nature of his categories reveal a great deal about his interests: time, space, language, and mathematics.

This is a well-organized passage; the categories are well-defined and Aristotle clearly explains how the members of each category have been classified.

When and How to Use Classification

When you’re asked to analyze and explain something, classification will be very useful.

Make sure you have a central idea (thesis).

Sort your information into meaningful groups.

Make sure you have a manageable number of categories—three or four.

Make sure the categories (or the elements in the categories) do not overlap.

Before writing, make sure the categories and central idea (thesis) are a good fit.

As you write, do not justify your classification unless this is somehow necessary to address a very bizarre free-response question.

Illustration

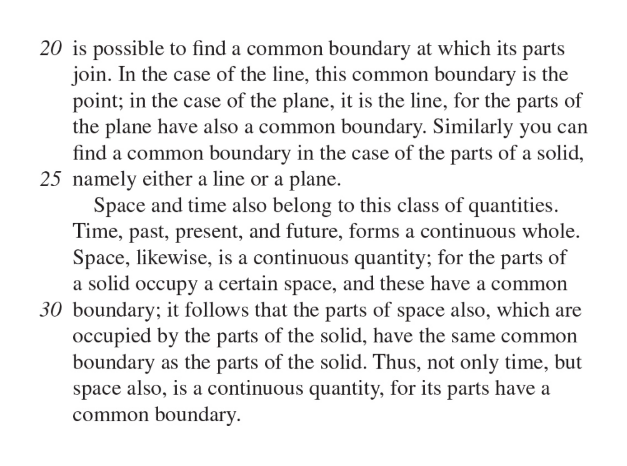

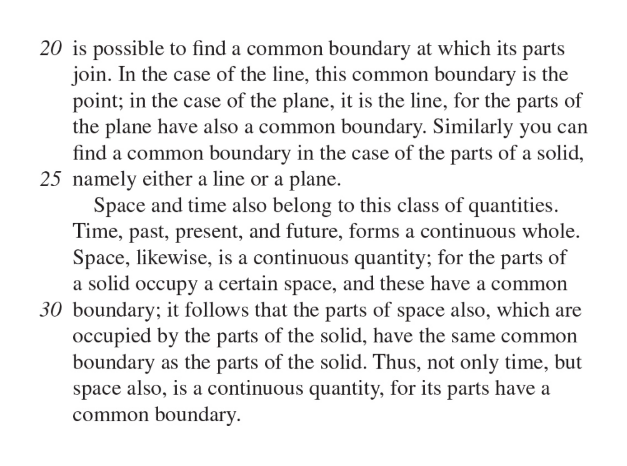

Read the following introduction paragraph from a student essay based on Candide, and as you do so, evaluate the effectiveness of the examples that it uses.

Surely you agree that the examples are not convincing, but you should also understand that they are not even relevant.

Implicit in the examples chosen is the reduction of the best of all possible worlds to the writer’s own tiny corner.

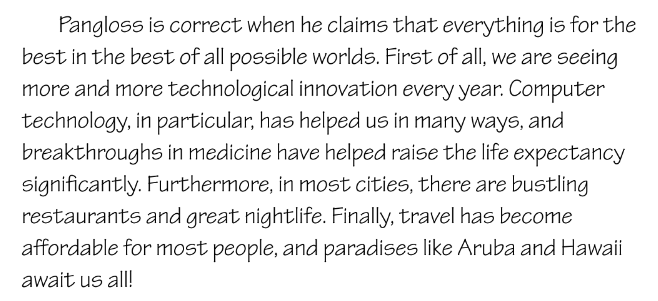

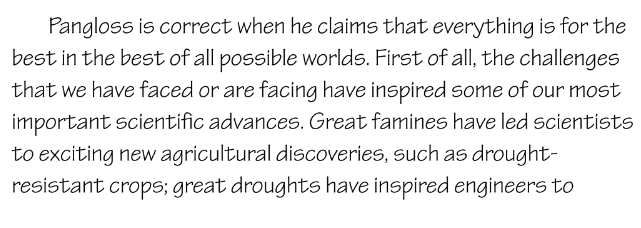

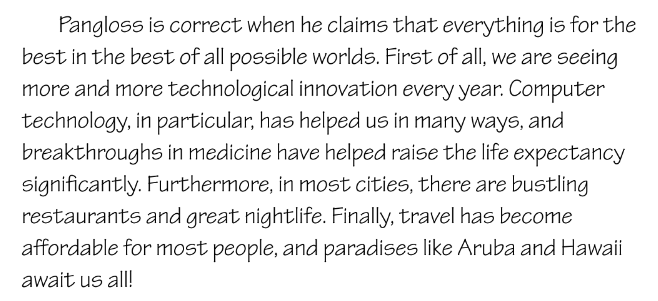

A better approach would be something as follows:

While the second essay may be naive, at least it does its best to substantiate an untenable position.

Without any doubt, the examples in the second passage are much more appropriate for the argument than those that were used in the first passage.

When and How to Use Example (Illustration)

Use examples that your reader (the person who reads your essays) will identify with and understand.

Draw your examples from “real life,” “real” culture (literature, art, classical music, and so on), and well-known folklore.

Make sure the example really does illustrate your point.

Introduce your examples using transitions, such as for example, for instance, case in point, and consider the case of.

A single example that is perfectly representative can serve to illustrate your point.

A series of short, less-perfect (but still relevant) examples can, by their accumulation, serve to illustrate your point.

Remember that you are in control of what you write.

Quality is more important than quantity; poorly chosen examples detract significantly from your presentation.

Analogy

Analogies are sometimes used to explain things that are difficult to understand by comparing them with things that are easier to understand.

You can also use an analogy to explain something that’s abstract by comparing it with something that’s concrete.

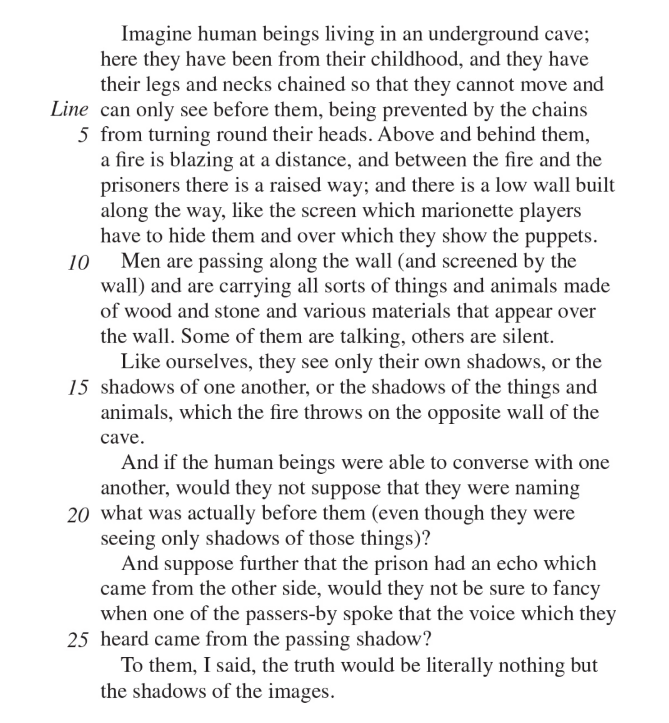

The most famous philosophical analogy serves as the basis for Plato’s “allegory of the cave.”

This is only part of the analogy, but you probably get the idea. Socrates uses this analogy to explain that we think that we see things just as they really are in our world, but that we are seeing only reflections of a greater truth, an abstraction that we fail to grasp. The cave is our world; the shadows are the objects and people that we “see.” We are like the prisoners, for we are not free to see what creates the shadows; the truth, made up of ideal forms, is out in the light.

When and How to Use Analogy

Use analogy for expository writing (explanation).

Do not use analogy for argumentative writing (argumentation).

Use analogy to explain something that is abstract or difficult to understand.

Make sure your audience will readily understand your “simple” or concrete subject.

Unit 3: Complex Rhetorical Modes

Process Analysis

Process analysis is a rhetorical mode that’s used by writers when they want to explain either how to do something or how something was done.

Process analysis can be an effective way of relating an experience.

Process analysis can be an effective way of relating an experience.

Take, for example, this excerpt from “On Dumpster Diving” from Travels with Lizbeth by Lars Eighner.

This is a good illustration of writing process analysis.

Although the content is ordered chronologically, the author adds explanatory examples and personal commentary to liven up the segment.

In this section, the author is outlining the psychological progression of a homeless scavenger based on his personal experience and exposing the excesses of a consumerist culture.

When and How to Use Process Analysis

Sequence is chronological and usually fixed—think of recipes.

When you use this device, make sure the stages of the process are clear, by using transitions (e.g., first, next, after two days, finally).

Make sure your terminology is appropriate for the reader.

Verify that every step is clear; an error or omission in an intermediate step may make the rest of the process analysis very confusing.

Cause and Effect

Cause and effect explains the processes responsible for the process.

Some cause-and-effect relationships are easy to describe.

For example:

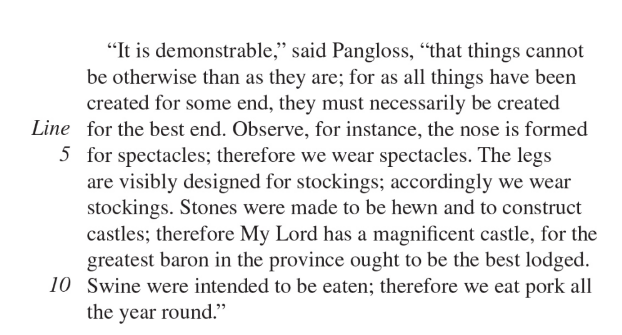

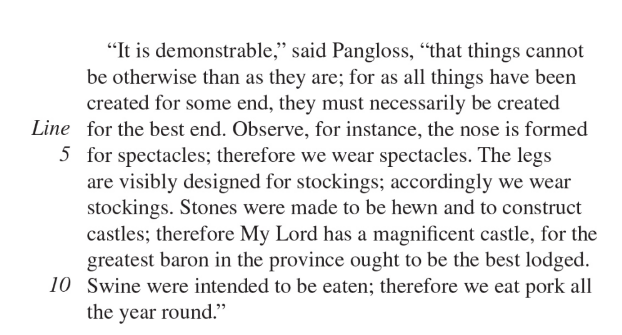

In this passage, Pangloss is using a series of cause-and-effect relationships to prove his point, that “things cannot be otherwise than as they are.” You see examples of this rhetorical mode all around you.

When and How to Use Cause and Effect

Do not confuse the relating of mere circumstances with a cause-and- effect relationship.

Turn your causal relationships into causes and effects by using carefully chosen examples.

Make sure to carefully address each step in a series of causal relationships; if you don’t, you risk losing your reader.

Definition

You are probably familiar with definitions; you see them every time you look up a word in the dictionary.

Hopefully when you write, you try to make sure your reader understands the words that you use.

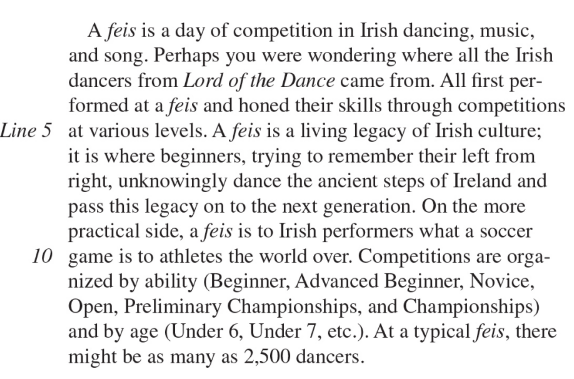

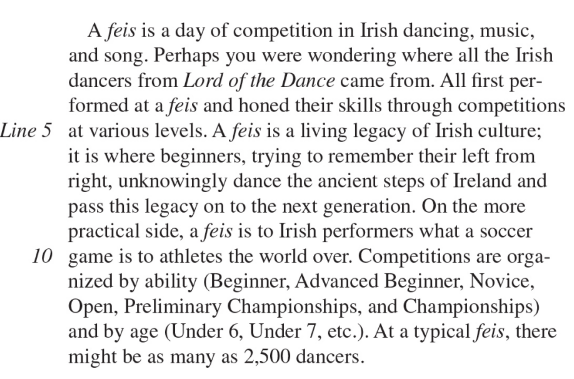

Here, for example, is a paragraph that defines feis (pronounced “fesh”).

The text begins with a simple definition, but the definition is elaborated and rhetorical forms are blended.

You probably noticed the comparison to a soccer match, and then there is an ill-conceived (imperfectly formed) attempt at categorisation (the divisions in the competition).

You can even contend that using Lord of the Dance as an example is appropriate.

The rhetorical form of definition can be used to explain a word or concept, but authors usually employ it to engage readers.

When and How to Use Definition

Keep your reason for defining something in mind as you’re writing.

Define key terms according to what you know of your audience, in other words, the readers of the essays; you don’t want to bore your reader by defining terms unnecessarily, nor do you want to perplex your reader by failing to define terms that may be obscure to your audience.

Explain the background (history) when it is relevant to your definition.

Define by negation when appropriate.

Combine definition with any number of other rhetorical modes when applicable.

Description

Description can help make expository or argumentative writing lively and interesting and hold the reader’s interest, which is vital, of course.

Oftentimes description serves as the primary rhetorical mode for an entire essay—or even an entire book.

It’s typically used to communicate a scene, a specific place, or a person to the reader.

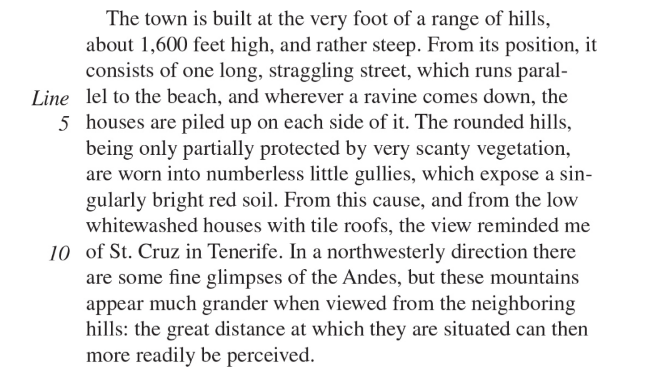

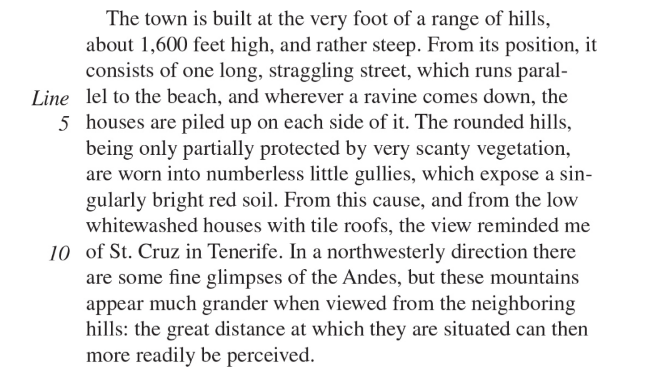

As an example of this, take a look at Charles Darwin’s depiction of Valparaíso, the chief seaport in Chile, in Voyage of the Beagle.

How and When to Use Description

When possible, call on all five senses: visual, auditory, olfactory (smell), gustatory (taste), and tactile.

Place the most striking examples at the beginnings and ends of your paragraphs (or essay) for maximum effect.

Show, don’t tell, using anecdotes and examples.

Use concrete nouns and adjectives; nouns, not adjectives, should dominate.

Concentrate on details that will convey the sense you’re trying to get across most effectively. (Remember the fish bladders!)

Employ figures of speech, especially similes, metaphors, and personification, when appropriate.

When describing people, try to focus on distinctive mannerisms; whenever possible, go beyond physical appearance.

Direct discourse (using dialogue or quotations) can be revealing and useful.

A brief illustrative anecdote is worth a thousand words.

To the extent possible, use action verbs.

Narration

A narrative is a story in which pieces of information are arranged in chronological order.

Narration can be an effective expository technique.

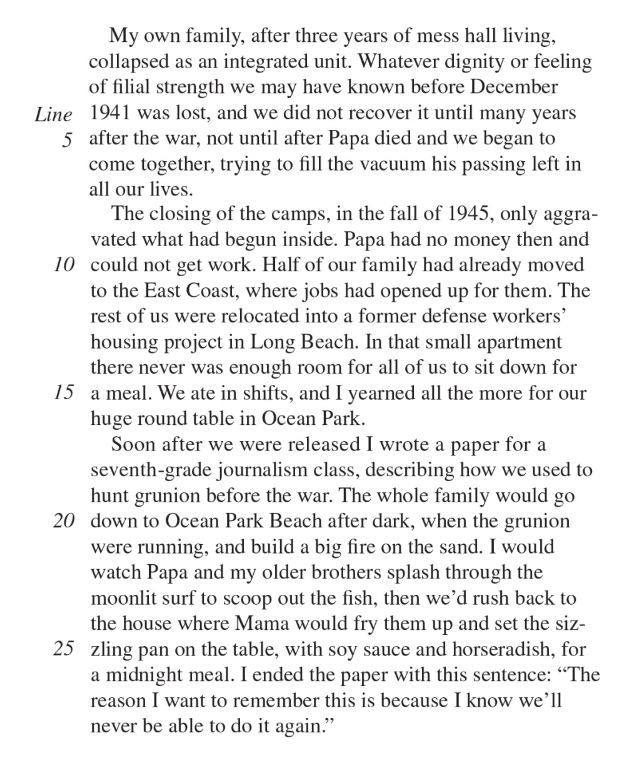

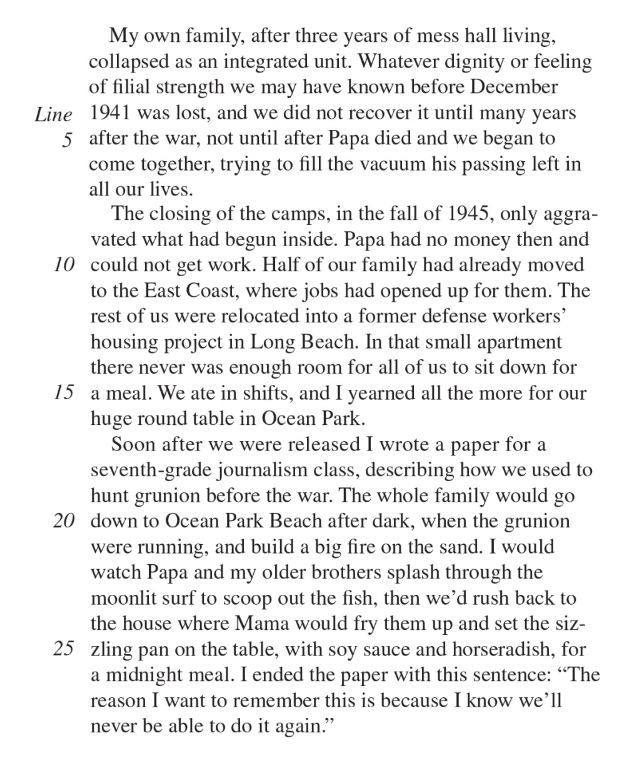

Decades after her experience in a Japanese internment camp, Jeanne Wakatsuki Houston decided to narrate her experiences before, during, and immediately after imprisonment.

She did not want to tell the story just for the story’s sake; she wanted to relay her experience to the public to exorcise personal demons and to raise public awareness about this period in history.

Here is a passage from this personal narrative.

The passage describes the period after the Wakatsuki family had lost their house in Ocean Park, California, when they were forced into detention.

How and When to Use Narration

When possible, structure the events in chronological order.

Make your story complete: make sure you have a beginning, middle, and end.

Provide a realistic setting (typically at the beginning).

Whenever possible, use action verbs; for example, write “the fighters tumbled to the ground,” rather than “there were fallen soldiers on the ground.”

Provide concrete and specific details.

Show, don’t tell.

Establish a clear point of view—if it’s clear who is narrating and why, then it will be easier to choose relevant details.

Include appropriate amounts of direct discourse (dialogue or quotations).

Induction and Deduction

Induction is a process in which specific examples are used to reach a general conclusion.

Deduction involves the use of a generalization to draw a conclusion about a specific case.

How and When to Use Induction and Deduction

Induction proceeds from the specific to a generalization.

Make sure you have sufficient evidence to support your claim.

Deduction is the process of applying a generalization to a specific case.

Make sure your generalization has sufficient credibility before applying it to specific cases.

Unit 4: Rhetorical Fallacies

The Rhetorical Fallacy Trap

A rhetorical fallacy is basically faulty reasoning leading to a conclusion the advertiser, author, or speaker wants you to make.

They pop up often—in ads, in statements by politicians, in appeals from charities, in arguments from your own friends and family.

Skilled communicators such as political speech writers use them deliberately.

A rhetorical fallacy uses (or rather, mis-uses) language in order to trick you into accepting the author’s conclusion.

Spotting and Avoiding Rhetorical Fallacies

Think of a rhetorical fallacy as “fake evidence.”

It seems to support a conclusion that the author wants the reader to accept, but—on close examination—it doesn’t really lead to that conclusion.

You can identify rhetorical fallacies (and avoid them in your own work) by following this process:

Identify the conclusion.

Identify the evidence.

Examine the evidence.

Common Rhetorical Fallacies

Emphasizing the Person In this class of rhetorical fallacies, the evidence focuses on the person who supports a conclusion, not on the merits of the conclusion itself.

Ad Populum or “bandwagon”: A certain political candidate is ahead in the polls.

Since most people are going to vote for him, you should too.

Otherwise you’ll just be wasting your vote.

The happy crowd on the beach described at the beginning of this chapter is another instance of the “bandwagon” fallacy. All of these people are having a great vacation at this resort; you should go there, and you’ll have fun too. The conclusion is an action the author (or the advertiser) wants you to take —vote for this candidate, book a vacation at this resort. No support is provided to explain why the candidate is the best choice, or why the resort is better than others. The very thin evidence is only that others are doing it.

Argument from Authority: This rhetorical fallacy focuses solely on the credentials or fame of the person recommending the product, without saying anything about the product itself.

Dr. X recommends this medication to his patients, or well-known musician Y always drives this brand of car. Are they being paid by the manufacturers to endorse those products, or do the products have attributes that really make them superior? You’ll never know.

Ad Hominem: This rhetorical fallacy turns to the other side of the coin and points out negative characteristics of the person who promotes an idea or action.

By implication, the action is as negative as the person who endorses it. The mayor was caught plagiarizing an essay in college and was accused of embezzlement by a former employer. Therefore, his claim that municipal taxes must increase to cover necessary road repairs has to be a lie and an attempt to steal taxpayers’ money. Nothing is said about the actual condition of the roads.

Dogmatism: The conclusion must be correct because the author or speaker says it is and she can’t possibly be wrong.

After all, she is an internationally recognized authority on the subject, or she is the CEO of the most profitable company on the planet. She wouldn’t have risen to that position if she were ever wrong. No other reasons are presented to support the conclusion, and no opposing viewpoints are even considered.

Presenting Only Part of the Truth

Equivocation: This type of fallacy leaves out facts that a reader or listener would need in order to make a thorough assessment of the conclusion.

Equivocation often relies on ambiguous definitions of words.

For example: For $50, your home insurer may cover $100,000 in flood damage.

Check at the "definitions" part of your insurance and you may notice that the insurer regards "water damage" to be sewer backup damage.

Overland flooding and roof ice jams are excluded.

You undoubtedly imagined those incidents would all cause "water damage," and the insurer is depending on it to get you to spend the extra $50.

Sentimental Appeals: Charities often use this tactic when they ask for donations.

Starving children or clear-cut mountains that were previously clothed in lush trees evoke emotions rather than intellect.

This rhetorical error omits sensible justifications for why the charity merits your support.

What has it done recently to fix the problem? How much of your donation goes to programming, executive salaries, and "team-building" events? How much is it spending to raise donations?

Arousing Fear

Slippery Slope: According to this rhetorical fallacy, if you eat at a fast-food takeout once, pretty soon you’ll never want to eat healthy, nourishing home-cooked meals again.

According to this rhetorical fallacy, if you consume fast food once, you'll never want to eat wholesome, home-cooked meals again.

Thus, you must never eat at a fast-food takeout.

The author scares the reader into agreeing that the first action must not happen.

Scare Tactics: Here the speaker or author is trying to frighten you into agreeing with him.

If you don’t commit to a two-year contract, your monthly rate won’t be protected and prices are going to go through the roof in the next couple of years.

Who says? On what evidence does he make that prediction?

Weakening an Opposing Argument

These rhetorical fallacies present an opposing view in such a weak light that almost nobody would agree with it.

Readers would, instead, accept the author’s apparently stronger conclusion.

Red Herring: Instead of addressing the key issues of an opposing argument, a red herring fallacy focuses attention on an insignificant or irrelevant factor.

For instance, you should avoid eating green vegetables (the conclusion) because of the risk of salmonella contamination (the red herring).

This fallacy avoids the main points of the opposing argument in favor of green vegetables (such as nutritional content and health benefits).

Straw Man: The writer creates a straw man—something that’s easy to knock down and tear apart—as the opposing viewpoint.

For example, the mayor wants taxpayers to pay for a new bridge that will go to a vast new development.

She claims that opponents of this investment don't think the new bridge is required because subdivision residents can drive downtown, across the existing bridge, and back up the other side of the river to the new neighborhood in an additional half hour.

If you live, work, or shop in the new subdivision, it's easy to argue for a new bridge.

Making Inaccurate Connections

Faulty analogy: One thing is compared with a second thing, but the comparison is exaggerated or misleading or unreasonable.

“Hiking on that trail is like descending into a dungeon of horrors from which you might never return.”

Perhaps it’s just a challenging trail that leads through thick woods and would give you a good workout.

But not many people would try it after hearing the speaker’s comparison.

Faulty causality (also called Post hoc ergo propter hoc): This type of fallacy assumes that because one event happened shortly before another, the first event must have caused the second. (That’s what the long Latin name refers to, by the way).

“She wore her old Brand X runners instead of her new Brand Y runners, therefore she lost the race.” Well, maybe.

But perhaps she lost the race because she hadn’t trained sufficiently, or because her knee was sore that day, or because others were simply faster.

No evidence is presented to prove that the first event caused the second.

Reverse Causation: Causal arguments are often faulty because the reverse causation is equally plausible.

For example, “Eating too much chocolate can make you depressed.”

Well, it’s just as likely that depressed people might feel the urge to eat too much chocolate.

If the author says “A caused B,” ask yourself, “Is it also possible that B caused A?”

Twisting the Language

Begging the Question: In this rhetorical fallacy, an assumption which is not proven is used as evidence that the conclusion is correct.

For instance, "high-altitude skiing is such a deadly activity," (the proof) "that no one under the age of 18 should be allowed to undertake it" (the conclusion).

If the writer had shown with facts or instances that high-altitude skiing is risky for youth, that would be a valid argument.

But he doesn't.

He uses that premise to justify his conclusion.

Circular Argument: This fallacy says essentially the same thing in both the conclusion and in the evidence that allegedly supports it.

Sally cares about others (the conclusion) since she's always willing to help (the evidence).

Someone who helps others cares for them. Both the conclusion and the evidence describe the same idea.

The speaker's conclusion would have been stronger if he had supplied examples of Sally helping others and other acts of kindness.

Mismatch Between Evidence and Conclusion

Missing the point: The author offers evidence that supports a conclusion—it’s just not the same conclusion that the author reaches.

Picture a presenter with stunning slides of northern plains meadows, deep woods, and subarctic tundra—grizzly bears' favored habitats.

She cites evidence showing that the grizzly population is dwindling and being forced into fewer territory as humans exploit their habitats.

As a result, she suggests transferring small groups of grizzlies to explore if they can adapt to areas with less human competition for land. She offers wetlands and high western mountains.

Non Sequitur: This Latin term means, “it doesn’t follow.”

In this rhetorical fallacy, the conclusion is not logically related to the evidence that preceded it.

Unstated Assumptions

False Dichotomy: This rhetorical fallacy assumes a black-and-white world in which there is no middle ground, no other alternative.

“If we don’t launch a preemptive attack and destroy the enemy first, they will destroy us.”

No consideration is given to other possibilities, such as a diplomatic solution or a small-scale limited strike.

Hasty Generalization: Here the author or speaker assumes that a limited experience foreshadows the entire experience.

“I could tell from the first few minutes that the movie was going to be unbearably boring, so I left rather than waste any more of my time.”

Maybe the director deliberately starts off slowly in order to intensify viewers’ reactions to the terrifying monster that is about to appear.

Non-testable hypothesis: In this rhetorical fallacy, anything that has not been proven false is assumed to be true; the author doesn’t need to prove it’s true.

For example, suppose an environmental group claims that average temperatures across the entire North American continent would fall by 1° Celsius if we switched completely to renewable energy.

Since we have never abandoned fossil fuels entirely, it’s impossible to prove that the group’s claim is false.

Therefore, the argument assumes it must be true.

AP English Language & Composition Ultimate Guide

Unit 1: Rhetoric and the Elements of Style

What is Rhetoric?

When we talk about rhetoric, we are talking about language as a means of persuasion.

More specifically, rhetoric refers to the strategies an author uses to impact an audience and persuade them of a specific idea.

The author uses X, which accomplishes Y and persuades the audience of Z.

X: This variable represents the specific rhetorical strategies an author uses.

An author might use a metaphor or a simile, or they might use formal diction or very casual diction.

Y: This variable refers to how the rhetorical strategies in the text impact the audience.

A catchy title is a rhetorical strategy designed to capture the audience’s attention.

Audience: Audience refers to the individuals the speaker is trying to persuade.

More generally, it is the people who read (or hear, in the case of a speech) a text.

Z: This variable represents a text’s theme or argument.

This is a developed idea an author wants to convey.

In other words, the theme is what the author is trying to persuade the audience of.

Rhetorical Strategies

Rhetorical strategies describe how an author uses language to construct a text.

“Rhetorical strategies” is a broad term, including basic diction and syntax, as well as more complicated uses of figurative language.

Diction

The diction questions you’ll see on the test will ask you to evaluate why an author’s choice of words is particularly effective, apt, or clear.

Often, the test will ask you to consider what style and/or tone an author’s use of diction develops.

Denotation and Connotation

Denotation refers to a word’s primary or literal significance, while connotation refers to the vast range of other meanings that a word suggests.

Context (and at times, author’s intent) determines which connotations may be appropriate for a word.

An author will carefully pick a particular word for its connotations, knowing or hoping a reader will make an additional inference as a result.

For example: I am looking at the sky.

The denotation of the underlined word should be as clear as a cloudless sky (the space, often blue, above the Earth’s surface).

Syntax

Syntax is the ordering of words in a sentence; it describes sentence structure.

Syntax in rhetorical strategies refers to the arrangement of words and phrases to achieve a desired effect.

It is used strategically by speakers or writers to convey meaning and emotion, persuade an audience, emphasize key points, create a sense of cohesion between ideas, and craft arguments more effectively.

For example:

Never was anything so gallant, so well outfitted, so brilliant, and so finely disposed as the two armies. The trumpets, fifes, reeds, drums, and cannon made such harmony as never was heard in Hell.

The first sentence depicts a beautiful battle.

The second begins similarly, but its phrases are structured to maximize the surprise at the end.

Being the last item on a list of military musical instruments, the cannons are expected to fit well.

It doesn't, but a new setup with the words "such harmony as never been heard..." distracts us before we can register our amazement.

We expect harmony to be beautiful and start to give the concluding word (Earth? Heaven?) until Voltaire surprises us with Hell.

Figurative Language

Figurative language is strictly defined as speech or writing that departs from literal meaning to achieve a special effect or meaning.

With malice toward none, with charity for all, with firmness in the right as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in, to bind up the nation’s wounds, to care for him who shall have borne the battle and for his widow

and his orphan, to do all which may achieve and cherish a just and lasting peace among ourselves and with all nations.

Do we literally interpret "to bind up the nation's wounds"? Certainly not.

Lincoln has personalized our country to make the suffering of individuals understandable to all of us.

What about "he who shall have borne the battle"? Lincoln's use of "his widow and his orphan" clarifies that "shall have borne the battle" meaning "shall have perished in battle."

Instead of talking about this group's suffering, Lincoln talks about individual sacrifice, which he knows would touch his audience.

Imagery

Imagery in figurative language is when an author uses vivid or metaphorical language to create a mental image that helps readers visualize what's being described.

Some examples of imagery include metaphors, similes, personification, and onomatopoeia.

Hyperbole

Hyperbole is overstatement or exaggeration; it is the use of figurative language that significantly exaggerates the facts for effect.

In many instances, but certainly not all, hyperbole is employed for comic effect.

For example: If you use too much figurative language in your essays, the AP readers will crucify you!

Clearly, this statement is a gross exaggeration; while the readers may give you a poor grade if you use figurative language that doesn’t suit the purposes of your essay, they will not kill you.

Understatement

Understatement is figurative language that presents the facts in a way that makes them appear much less significant than they really are.

Understatement is almost always used for comic effect.

For example:

After dinner, they came and took into custody Doctor Pangloss and his pupil Candide, the one for speaking his mind and the other for appearing to approve what he heard. They were

conducted to separate apartments, which were extremely cool and where they were never bothered by the sun.

Taking the last statement literally will lead you wrong.

The understatement in this example ("They were brought to separate apartments, which were extremely cool and where they were never bothered by the sun") implies that the poor men were dumped into horrifyingly gloomy, dank, and frigid jail cells.

Simile - A simile is a comparison between two unlike objects, in which the two parts are connected with a term such as like or as.

For example: The birds are like black arrows flying across the sky.

Metaphor - A metaphor is a simile without a connecting term such as like or as.

For example: The birds are black arrows flying across the sky.

Birds are not arrows, but the commonalities (both are long and sleek, and they travel swiftly through the air—and both have feathers) allow us to easily grasp the image.

Extended Metaphor - An extended metaphor is precisely what it sounds like—it is a metaphor that lasts for longer than just one phrase or sentence.

For example:

During the time I have voyaged on this ship, I have avoided the cabin; rather, I have remained on deck, battered by wind and rain, but able to see moonlight on the water. I do not wish to go below decks now.

As strange as it may appear, this passage is not about maritime navigation.

The writer uses figurative language to deepen the metaphor of the ship's journey, which represents the passage of life.

On deck, you're exposed to the weather but can see beautiful sights.

The cabin is safe but not very exciting.

Having made the tough, hazardous, but gratifying option of staying on deck, it would be a personal failure to wish for the cabin's safety, comfort, and limited horizons later in life.

Symbolism - A symbol is a concrete object that represents an abstract idea.

For example: The Christian soldiers paused to remember the lamb.

In this case, the lamb is a symbol.

The lamb is a concrete object that represents an abstract idea.

In this case, the lamb symbolizes the legacy of Jesus Christ.

Personification

Personification is the figurative device in which inanimate objects or concepts are given the thoughts, feelings, or actions of a human.

It can enhance our emotional response because we usually attribute more emotional significance to other humans than to things or concepts.

For example:

He had been wrestling with lethargy for days, and every time that he thought that he was close to victory, his adversary escaped his hold.

This figurative wrestling bout, in which lethargy is personified as the opponent to the author of this text, brings the conflict to life—human life.

If you don't accept this, consider the alternative: he attempted to quit being lethargic but failed.

This doesn't sound too lively.

Anthropomorphism occurs when non-human objects are given the physical shape of a human, e.g., the legs of a table, the face of a clock, the arms of a tree.

Circumlocution and Euphemism

Circumlocation is a form of communication in which the speaker's meaning is not directly expressed but implied, often through metaphors or other forms of figurative language.

It can be used to build suspense, hide sensitive information, or simply express emotions and feelings more effectively than literal words can do.

A euphemism is a word or words that are used to avoid employing an unpleasant or offensive term.

Paradox

A paradox contains two elements which cannot both be true at the same time (although usually each one could be true on its own).

The classic example is the Cretan Liar Paradox, attributed to the sixth- century BCE philosopher and poet Epimenides. He was from Crete, and his famous paradox says, “All Cretans are liars.”

Rhetorical Question

A rhetorical question is a question whose answer is obvious; these types of questions do not need to be answered—and usually aren’t.

Rhetorical questions attempt to prove something without actually presenting an argument; sometimes they’re used as a form of irony, in which something is stated, but its opposite is meant.

For example:

Given how cheap the most fattening foods are, is it any wonder obesity is on the rise? (no irony)

Aren’t AP Exams great fun? (with irony)

Irony and Satire

Irony is a figure of speech in which words are used to convey the opposite of their literal meaning.

It can be used to make a point, add humor or emphasize something.

Verbal Irony

Verbal irony refers to the process of stating something but meaning the opposite of what is stated.

In cases of verbal irony, the audience can anticipate the dialogue or specific language used in a text.

The author may use a common saying, situation, or emotional experience to build up the audience’s expectation.

For example, an author may describe an experience while shopping. When the author enters the store, the salesperson says, “Hello, how can you help me?” This would be ironic because the expectation is that the salesperson would say the opposite, “How can I help you?”

Sarcasm is simply verbal irony used with the intent to injure.

It’s often impossible to discern between irony and sarcasm, and, more often than not, sarcasm is in the mind of the beholder.

For example, when someone says "That's great" but they mean something completely different.

Situational Irony refers to a circumstance that runs contrary to what was expected.

For example: Suppose you live in Seattle during the rainy season and plan a vacation to sunny Phoenix. While you are in Phoenix, it rains every day there, but is sunny the entire week in Seattle.

Satire - something is portrayed in a way that’s deliberately distorted to achieve comic effect.

Implicit in most satire is the author’s desire to critique what is being mocked.

Example: An example of satire would be Jonathan Swift's "A Modest Proposal". In this essay, Swift suggests the Irish people should eat their own children in order to solve poverty and hunger. This proposal was obviously not meant to be taken seriously - it was intended as a way for Swift to mock the British government's indifference towards its citizens' plight.

The following terms are similar, but not identical. Know the differences.

Satire: A social or political criticism that relies heavily on irony, sarcasm, and often humor

Parody: Imitation for comic effect

Lampoon: Sharp ridicule of the behavior or character of a person or institution

Caricature: A ludicrous exaggeration of the defects of persons or things

Style, Tone, and Mood

Style is the general manner of expression used in a text.

It describes how the author uses language to get his or her point across (e.g., pedantic, scientific, or emotive).

Tone describes the speaker’s attitude toward the subject.

Tone describes how the author seems to be feeling (e.g., optimistic, ironic, or playful).

Mood describes how the text makes the audience feel.

For example:

Our left fielder couldn’t hit the floor if he fell out of bed! After striking out twice (once with the bases loaded!), he grounded into a double-play. My grandmother runs faster than he does! In the eighth inning, he misjudged a routine fly ball, which brought in the winning run. What a jerk! Why didn’t the club

trade him last week when it was still possible? What’s wrong with you guys?

The style is simple, direct, unsophisticated, truculent, and even crass.

The tone is angry, brash, emotional, and even aggressive.

The mood is stressed and concerned.

Pay close attention to the final sentence: The speaker accuses the audience directly with “you,” which could make the audience feel guilty, defensive, or angry.

Classical Appeals

Logos is an appeal to reason and logic.

An argument that uses logos to persuade needs to provide things like objective evidence, hard facts, statistics, or logical strategies such as cause and effect to back up its claim.

Ethos is an appeal to the speaker’s credibility—whether he or she is to be believed on the basis of his or her character and expertise.

Pathos is an appeal to the emotions, values, or desires of the audience.

Unit 2: Basic Rhetorical Modes

Rhetorical Modes

Rhetorical modes are ways of using language that are intended to have an effect on the audience.

Classification

Aristotle liked to classify, and he did so quite often. Some of his classifications have stood the test of time, including the one below, which is the beginning of Part 6 of an essay entitled “Categories.”

Here, Aristotle’s division of quantity into two categories (discrete and continuous) makes sense.

The examples that he uses to illustrate the nature of his categories reveal a great deal about his interests: time, space, language, and mathematics.

This is a well-organized passage; the categories are well-defined and Aristotle clearly explains how the members of each category have been classified.

When and How to Use Classification

When you’re asked to analyze and explain something, classification will be very useful.

Make sure you have a central idea (thesis).

Sort your information into meaningful groups.

Make sure you have a manageable number of categories—three or four.

Make sure the categories (or the elements in the categories) do not overlap.

Before writing, make sure the categories and central idea (thesis) are a good fit.

As you write, do not justify your classification unless this is somehow necessary to address a very bizarre free-response question.

Illustration

Read the following introduction paragraph from a student essay based on Candide, and as you do so, evaluate the effectiveness of the examples that it uses.

Surely you agree that the examples are not convincing, but you should also understand that they are not even relevant.

Implicit in the examples chosen is the reduction of the best of all possible worlds to the writer’s own tiny corner.

A better approach would be something as follows:

While the second essay may be naive, at least it does its best to substantiate an untenable position.

Without any doubt, the examples in the second passage are much more appropriate for the argument than those that were used in the first passage.

When and How to Use Example (Illustration)

Use examples that your reader (the person who reads your essays) will identify with and understand.

Draw your examples from “real life,” “real” culture (literature, art, classical music, and so on), and well-known folklore.

Make sure the example really does illustrate your point.

Introduce your examples using transitions, such as for example, for instance, case in point, and consider the case of.

A single example that is perfectly representative can serve to illustrate your point.

A series of short, less-perfect (but still relevant) examples can, by their accumulation, serve to illustrate your point.

Remember that you are in control of what you write.

Quality is more important than quantity; poorly chosen examples detract significantly from your presentation.

Analogy

Analogies are sometimes used to explain things that are difficult to understand by comparing them with things that are easier to understand.

You can also use an analogy to explain something that’s abstract by comparing it with something that’s concrete.

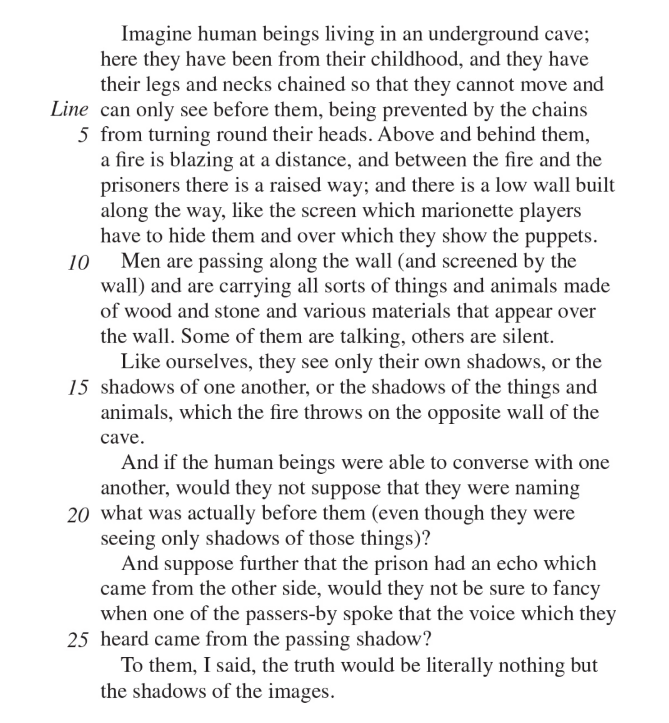

The most famous philosophical analogy serves as the basis for Plato’s “allegory of the cave.”

This is only part of the analogy, but you probably get the idea. Socrates uses this analogy to explain that we think that we see things just as they really are in our world, but that we are seeing only reflections of a greater truth, an abstraction that we fail to grasp. The cave is our world; the shadows are the objects and people that we “see.” We are like the prisoners, for we are not free to see what creates the shadows; the truth, made up of ideal forms, is out in the light.

When and How to Use Analogy

Use analogy for expository writing (explanation).

Do not use analogy for argumentative writing (argumentation).

Use analogy to explain something that is abstract or difficult to understand.

Make sure your audience will readily understand your “simple” or concrete subject.

Unit 3: Complex Rhetorical Modes

Process Analysis

Process analysis is a rhetorical mode that’s used by writers when they want to explain either how to do something or how something was done.

Process analysis can be an effective way of relating an experience.

Process analysis can be an effective way of relating an experience.

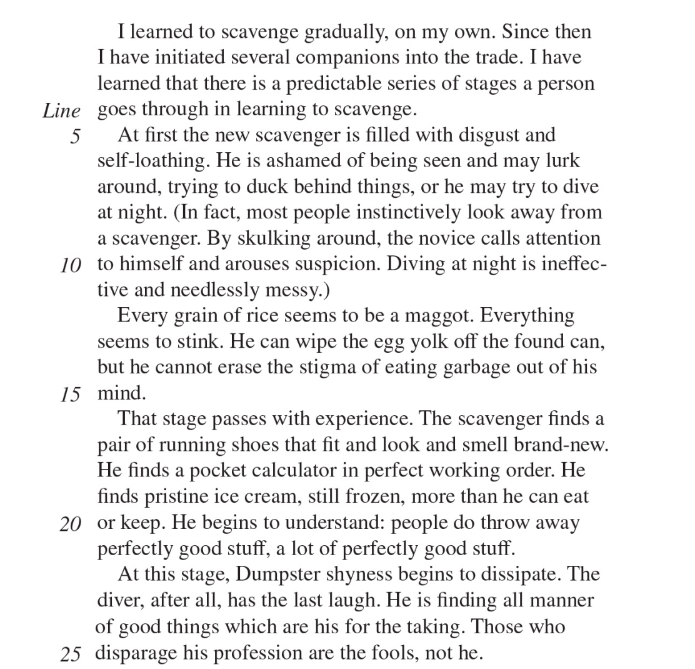

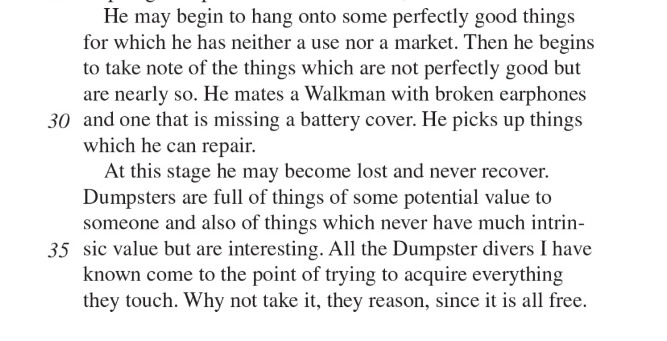

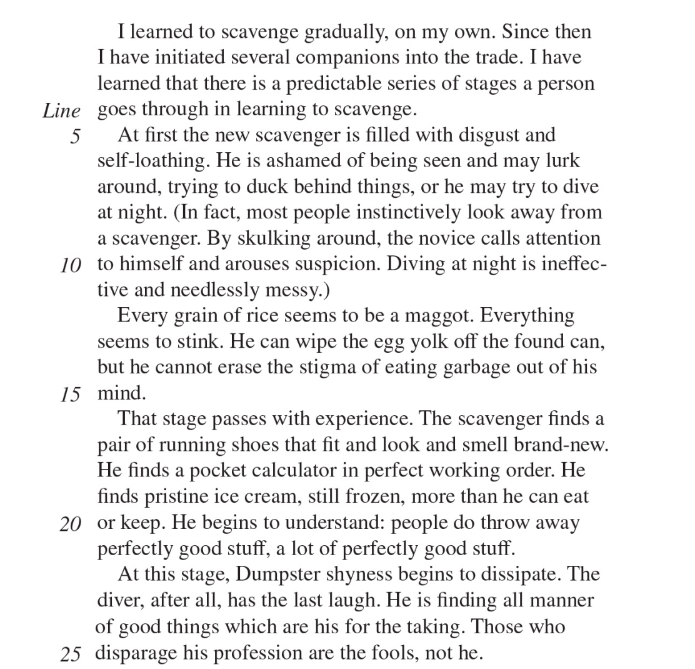

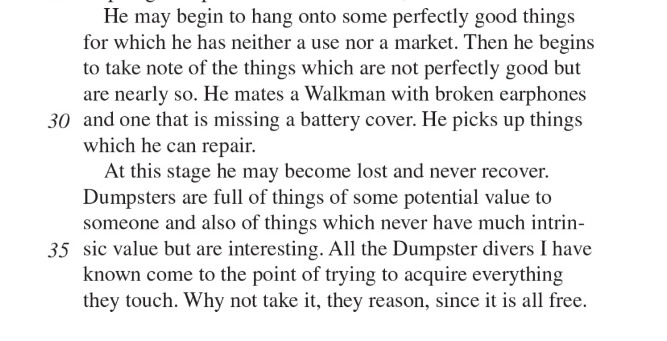

Take, for example, this excerpt from “On Dumpster Diving” from Travels with Lizbeth by Lars Eighner.

This is a good illustration of writing process analysis.

Although the content is ordered chronologically, the author adds explanatory examples and personal commentary to liven up the segment.

In this section, the author is outlining the psychological progression of a homeless scavenger based on his personal experience and exposing the excesses of a consumerist culture.

When and How to Use Process Analysis

Sequence is chronological and usually fixed—think of recipes.

When you use this device, make sure the stages of the process are clear, by using transitions (e.g., first, next, after two days, finally).

Make sure your terminology is appropriate for the reader.

Verify that every step is clear; an error or omission in an intermediate step may make the rest of the process analysis very confusing.

Cause and Effect

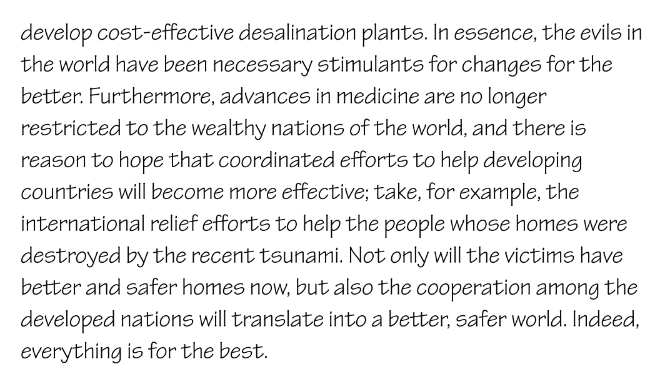

Cause and effect explains the processes responsible for the process.

Some cause-and-effect relationships are easy to describe.

For example:

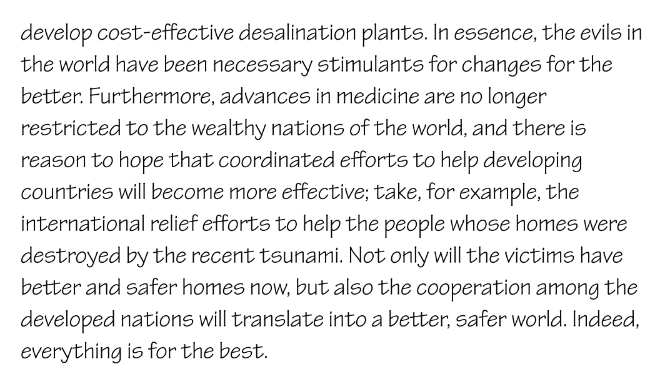

In this passage, Pangloss is using a series of cause-and-effect relationships to prove his point, that “things cannot be otherwise than as they are.” You see examples of this rhetorical mode all around you.

When and How to Use Cause and Effect

Do not confuse the relating of mere circumstances with a cause-and- effect relationship.

Turn your causal relationships into causes and effects by using carefully chosen examples.

Make sure to carefully address each step in a series of causal relationships; if you don’t, you risk losing your reader.

Definition

You are probably familiar with definitions; you see them every time you look up a word in the dictionary.

Hopefully when you write, you try to make sure your reader understands the words that you use.

Here, for example, is a paragraph that defines feis (pronounced “fesh”).

The text begins with a simple definition, but the definition is elaborated and rhetorical forms are blended.

You probably noticed the comparison to a soccer match, and then there is an ill-conceived (imperfectly formed) attempt at categorisation (the divisions in the competition).

You can even contend that using Lord of the Dance as an example is appropriate.

The rhetorical form of definition can be used to explain a word or concept, but authors usually employ it to engage readers.

When and How to Use Definition

Keep your reason for defining something in mind as you’re writing.

Define key terms according to what you know of your audience, in other words, the readers of the essays; you don’t want to bore your reader by defining terms unnecessarily, nor do you want to perplex your reader by failing to define terms that may be obscure to your audience.

Explain the background (history) when it is relevant to your definition.

Define by negation when appropriate.

Combine definition with any number of other rhetorical modes when applicable.

Description

Description can help make expository or argumentative writing lively and interesting and hold the reader’s interest, which is vital, of course.

Oftentimes description serves as the primary rhetorical mode for an entire essay—or even an entire book.

It’s typically used to communicate a scene, a specific place, or a person to the reader.

As an example of this, take a look at Charles Darwin’s depiction of Valparaíso, the chief seaport in Chile, in Voyage of the Beagle.

How and When to Use Description

When possible, call on all five senses: visual, auditory, olfactory (smell), gustatory (taste), and tactile.

Place the most striking examples at the beginnings and ends of your paragraphs (or essay) for maximum effect.

Show, don’t tell, using anecdotes and examples.

Use concrete nouns and adjectives; nouns, not adjectives, should dominate.

Concentrate on details that will convey the sense you’re trying to get across most effectively. (Remember the fish bladders!)

Employ figures of speech, especially similes, metaphors, and personification, when appropriate.

When describing people, try to focus on distinctive mannerisms; whenever possible, go beyond physical appearance.

Direct discourse (using dialogue or quotations) can be revealing and useful.

A brief illustrative anecdote is worth a thousand words.

To the extent possible, use action verbs.

Narration

A narrative is a story in which pieces of information are arranged in chronological order.

Narration can be an effective expository technique.

Decades after her experience in a Japanese internment camp, Jeanne Wakatsuki Houston decided to narrate her experiences before, during, and immediately after imprisonment.

She did not want to tell the story just for the story’s sake; she wanted to relay her experience to the public to exorcise personal demons and to raise public awareness about this period in history.

Here is a passage from this personal narrative.

The passage describes the period after the Wakatsuki family had lost their house in Ocean Park, California, when they were forced into detention.

How and When to Use Narration

When possible, structure the events in chronological order.

Make your story complete: make sure you have a beginning, middle, and end.

Provide a realistic setting (typically at the beginning).

Whenever possible, use action verbs; for example, write “the fighters tumbled to the ground,” rather than “there were fallen soldiers on the ground.”

Provide concrete and specific details.

Show, don’t tell.

Establish a clear point of view—if it’s clear who is narrating and why, then it will be easier to choose relevant details.

Include appropriate amounts of direct discourse (dialogue or quotations).

Induction and Deduction

Induction is a process in which specific examples are used to reach a general conclusion.

Deduction involves the use of a generalization to draw a conclusion about a specific case.

How and When to Use Induction and Deduction

Induction proceeds from the specific to a generalization.

Make sure you have sufficient evidence to support your claim.

Deduction is the process of applying a generalization to a specific case.

Make sure your generalization has sufficient credibility before applying it to specific cases.

Unit 4: Rhetorical Fallacies

The Rhetorical Fallacy Trap

A rhetorical fallacy is basically faulty reasoning leading to a conclusion the advertiser, author, or speaker wants you to make.

They pop up often—in ads, in statements by politicians, in appeals from charities, in arguments from your own friends and family.

Skilled communicators such as political speech writers use them deliberately.

A rhetorical fallacy uses (or rather, mis-uses) language in order to trick you into accepting the author’s conclusion.

Spotting and Avoiding Rhetorical Fallacies

Think of a rhetorical fallacy as “fake evidence.”

It seems to support a conclusion that the author wants the reader to accept, but—on close examination—it doesn’t really lead to that conclusion.

You can identify rhetorical fallacies (and avoid them in your own work) by following this process:

Identify the conclusion.

Identify the evidence.

Examine the evidence.

Common Rhetorical Fallacies

Emphasizing the Person In this class of rhetorical fallacies, the evidence focuses on the person who supports a conclusion, not on the merits of the conclusion itself.

Ad Populum or “bandwagon”: A certain political candidate is ahead in the polls.

Since most people are going to vote for him, you should too.

Otherwise you’ll just be wasting your vote.

The happy crowd on the beach described at the beginning of this chapter is another instance of the “bandwagon” fallacy. All of these people are having a great vacation at this resort; you should go there, and you’ll have fun too. The conclusion is an action the author (or the advertiser) wants you to take —vote for this candidate, book a vacation at this resort. No support is provided to explain why the candidate is the best choice, or why the resort is better than others. The very thin evidence is only that others are doing it.

Argument from Authority: This rhetorical fallacy focuses solely on the credentials or fame of the person recommending the product, without saying anything about the product itself.

Dr. X recommends this medication to his patients, or well-known musician Y always drives this brand of car. Are they being paid by the manufacturers to endorse those products, or do the products have attributes that really make them superior? You’ll never know.

Ad Hominem: This rhetorical fallacy turns to the other side of the coin and points out negative characteristics of the person who promotes an idea or action.

By implication, the action is as negative as the person who endorses it. The mayor was caught plagiarizing an essay in college and was accused of embezzlement by a former employer. Therefore, his claim that municipal taxes must increase to cover necessary road repairs has to be a lie and an attempt to steal taxpayers’ money. Nothing is said about the actual condition of the roads.

Dogmatism: The conclusion must be correct because the author or speaker says it is and she can’t possibly be wrong.

After all, she is an internationally recognized authority on the subject, or she is the CEO of the most profitable company on the planet. She wouldn’t have risen to that position if she were ever wrong. No other reasons are presented to support the conclusion, and no opposing viewpoints are even considered.

Presenting Only Part of the Truth

Equivocation: This type of fallacy leaves out facts that a reader or listener would need in order to make a thorough assessment of the conclusion.

Equivocation often relies on ambiguous definitions of words.

For example: For $50, your home insurer may cover $100,000 in flood damage.

Check at the "definitions" part of your insurance and you may notice that the insurer regards "water damage" to be sewer backup damage.

Overland flooding and roof ice jams are excluded.

You undoubtedly imagined those incidents would all cause "water damage," and the insurer is depending on it to get you to spend the extra $50.

Sentimental Appeals: Charities often use this tactic when they ask for donations.

Starving children or clear-cut mountains that were previously clothed in lush trees evoke emotions rather than intellect.

This rhetorical error omits sensible justifications for why the charity merits your support.

What has it done recently to fix the problem? How much of your donation goes to programming, executive salaries, and "team-building" events? How much is it spending to raise donations?

Arousing Fear

Slippery Slope: According to this rhetorical fallacy, if you eat at a fast-food takeout once, pretty soon you’ll never want to eat healthy, nourishing home-cooked meals again.

According to this rhetorical fallacy, if you consume fast food once, you'll never want to eat wholesome, home-cooked meals again.

Thus, you must never eat at a fast-food takeout.

The author scares the reader into agreeing that the first action must not happen.

Scare Tactics: Here the speaker or author is trying to frighten you into agreeing with him.

If you don’t commit to a two-year contract, your monthly rate won’t be protected and prices are going to go through the roof in the next couple of years.

Who says? On what evidence does he make that prediction?

Weakening an Opposing Argument

These rhetorical fallacies present an opposing view in such a weak light that almost nobody would agree with it.

Readers would, instead, accept the author’s apparently stronger conclusion.

Red Herring: Instead of addressing the key issues of an opposing argument, a red herring fallacy focuses attention on an insignificant or irrelevant factor.

For instance, you should avoid eating green vegetables (the conclusion) because of the risk of salmonella contamination (the red herring).

This fallacy avoids the main points of the opposing argument in favor of green vegetables (such as nutritional content and health benefits).

Straw Man: The writer creates a straw man—something that’s easy to knock down and tear apart—as the opposing viewpoint.

For example, the mayor wants taxpayers to pay for a new bridge that will go to a vast new development.

She claims that opponents of this investment don't think the new bridge is required because subdivision residents can drive downtown, across the existing bridge, and back up the other side of the river to the new neighborhood in an additional half hour.

If you live, work, or shop in the new subdivision, it's easy to argue for a new bridge.

Making Inaccurate Connections

Faulty analogy: One thing is compared with a second thing, but the comparison is exaggerated or misleading or unreasonable.

“Hiking on that trail is like descending into a dungeon of horrors from which you might never return.”

Perhaps it’s just a challenging trail that leads through thick woods and would give you a good workout.

But not many people would try it after hearing the speaker’s comparison.

Faulty causality (also called Post hoc ergo propter hoc): This type of fallacy assumes that because one event happened shortly before another, the first event must have caused the second. (That’s what the long Latin name refers to, by the way).

“She wore her old Brand X runners instead of her new Brand Y runners, therefore she lost the race.” Well, maybe.

But perhaps she lost the race because she hadn’t trained sufficiently, or because her knee was sore that day, or because others were simply faster.

No evidence is presented to prove that the first event caused the second.

Reverse Causation: Causal arguments are often faulty because the reverse causation is equally plausible.

For example, “Eating too much chocolate can make you depressed.”

Well, it’s just as likely that depressed people might feel the urge to eat too much chocolate.

If the author says “A caused B,” ask yourself, “Is it also possible that B caused A?”

Twisting the Language

Begging the Question: In this rhetorical fallacy, an assumption which is not proven is used as evidence that the conclusion is correct.

For instance, "high-altitude skiing is such a deadly activity," (the proof) "that no one under the age of 18 should be allowed to undertake it" (the conclusion).

If the writer had shown with facts or instances that high-altitude skiing is risky for youth, that would be a valid argument.

But he doesn't.

He uses that premise to justify his conclusion.

Circular Argument: This fallacy says essentially the same thing in both the conclusion and in the evidence that allegedly supports it.

Sally cares about others (the conclusion) since she's always willing to help (the evidence).

Someone who helps others cares for them. Both the conclusion and the evidence describe the same idea.

The speaker's conclusion would have been stronger if he had supplied examples of Sally helping others and other acts of kindness.

Mismatch Between Evidence and Conclusion

Missing the point: The author offers evidence that supports a conclusion—it’s just not the same conclusion that the author reaches.

Picture a presenter with stunning slides of northern plains meadows, deep woods, and subarctic tundra—grizzly bears' favored habitats.

She cites evidence showing that the grizzly population is dwindling and being forced into fewer territory as humans exploit their habitats.

As a result, she suggests transferring small groups of grizzlies to explore if they can adapt to areas with less human competition for land. She offers wetlands and high western mountains.

Non Sequitur: This Latin term means, “it doesn’t follow.”

In this rhetorical fallacy, the conclusion is not logically related to the evidence that preceded it.

Unstated Assumptions

False Dichotomy: This rhetorical fallacy assumes a black-and-white world in which there is no middle ground, no other alternative.

“If we don’t launch a preemptive attack and destroy the enemy first, they will destroy us.”

No consideration is given to other possibilities, such as a diplomatic solution or a small-scale limited strike.

Hasty Generalization: Here the author or speaker assumes that a limited experience foreshadows the entire experience.

“I could tell from the first few minutes that the movie was going to be unbearably boring, so I left rather than waste any more of my time.”

Maybe the director deliberately starts off slowly in order to intensify viewers’ reactions to the terrifying monster that is about to appear.

Non-testable hypothesis: In this rhetorical fallacy, anything that has not been proven false is assumed to be true; the author doesn’t need to prove it’s true.

For example, suppose an environmental group claims that average temperatures across the entire North American continent would fall by 1° Celsius if we switched completely to renewable energy.

Since we have never abandoned fossil fuels entirely, it’s impossible to prove that the group’s claim is false.

Therefore, the argument assumes it must be true.

Knowt

Knowt