Chapter 10: Early Medieval Art

Key Notes

Time Period

Merovingian Art: 481–714 (from France)

Hiberno-Saxon Art: 6th–8th centuries (British Isles)

Culture, beliefs, and physical settings

Early Medieval art is a part of the medieval artistic tradition.

In the Early Medieval period, royal courts emphasized the study of theology, music, and writing.

Early Medieval art avoids naturalism and emphasizes stylistic variety.

Text is often incorporated into Early Medieval artworks.

Cultural interactions

There is an active exchange of artistic ideas throughout the Middle Ages.

There is a great influence of Roman art on Early Medieval art.

Audience, functions and patron

Works of art were often displayed in religious or court settings.

Surviving architecture is mostly religious.

Theories and Interpretations

The study of art history is shaped by changing analyses based on scholarship, theories, context, and written records.

Contextual information comes from written records that are religious or civic.

Historical Background

In the year 600, almost everything that was known was old.

The great technological breakthroughs of the Romans were either lost to history or beyond the capabilities of the migratory people of the seventh century.

This was the age of mass migrations sweeping across Europe, an age epitomized by the fifth-century king, Attila the Hun, whose hordes were famous for despoiling all before them.

The Vikings from Scandinavia, in their speedy boats, flew across the North Sea and invaded the British Isles and colonized parts of France.

Other groups, like the notorious Vandals, did much to destroy the remains of Roman civilization.

So desperate was this era that historians named it the “Dark Ages,” a term that more reflects our knowledge of the times than the times themselves.

However, stability in Europe was reached at the end of the eighth century when a group of Frankish kings, most notably Charlemagne, built an impressive empire whose capital was centered in Aachen, Germany.

Patronage and Artistic Life

Monasteries were the principal centers of learning in an age when even the emperor, Charlemagne, could read, but not write more than his name.

Artists who could both write and draw were particularly honored for the creation of manuscripts.

The concept that artists should be creative and communicate something new in each work was unknown in the Middle Ages.

Scribes copied the Bible and medical treatises, not modern literature or folk stories.

Scribes had to retain the original phrasing, while artists had to balance conventional and new methods.

Thus, a manuscript's text is usually an exact duplicate of a constantly recopied book, but the pictures offer the artist considerable latitude.

Early Medieval Art

One of the great glories of medieval art is the decoration of manuscript books, called codices, which were improvements over ancient scrolls both for ease of use and durability.

A codex was made of resilient antelope or calf hide, called vellum, or sheep or goat hide, called parchment.

These hides were more durable than the friable papyrus used in making ancient scrolls.

Hides were cut into sheets and soaked in lime in order to free them from oil and hair.

The skin was then dried and perhaps chalk was added to whiten the surface.

Artisans then prepared the skins by scraping them down to an even thickness with a sharp knife; each page had to be rubbed smooth to remove impurities.

The hides were then folded to form small booklets of eight pages.

The backbone of the hide was arranged so that the spine of the animal ran across the page horizontally.

This minimized movement when the hide dried and tried to return to the shape of the animal, perhaps causing the paint to flake.

Illuminations were painted mostly by monks or nuns who wrote in rooms called scriptoria, or writing places, that had no heat or light, to prevent fires.

Vows of silence were maintained to limit mistakes.

A team often worked on one book; scribes copied the text and illustrators drew capital letters as painters illustrated scenes from the Bible.

Scriptorium: a place in a monastery where monks wrote manuscripts

Manuscript books had a sacred quality.

The word of God; had to be treated with appropriate deference.

Covered with bindings of wood or leather, and gold leaf was lavished on the surfaces.

Precious gems were inset on the cover.

Objects are done in the cloisonné technique, with horror vacui designs featuring animal style decoration.

Interlace patternings are common.

Images enjoy an elaborate symmetry, with animals alternating with geometric designs.

Merovingian Art

Merovingians: A dynasty of Frankish kings who, according to tradition, descended from Merovech, chief of the Salian Franks.

Power was solidified under Clovis (reigned 481–511) who ruled what is today France and southwestern Germany.

The Frankish custom of dividing property among sons when a father died led to instability because Clovis’s four male descendants fought over their patrimony.

Royal burials supply almost all our knowledge of Merovingian art.

A wide range of metal objects were interred with the dead, including personal jewelry items like brooches, discs, pins, earrings, and bracelets.

Garment clasps, called fibulae, were particular specialties.

They were often inlaid with hard stones, like garnets, and were made using chasing and cloisonné techniques.

Chasing: to ornament metal by indenting into a surface with a hammer

Cloissonné: enamelwork in which colored areas are separated by thin bands of metal, usually gold or bronze

➼ Merovingian looped fibulae

Details

Early medieval Europe

Mid-6th century

Made of silver gilt worked in filigree with semiprecious stones, inlays of garnets and other stones

Found in Musee d’Archeologie Nationale, Saint-Germain-en-Laye, France

Form

Zoomorphic elements—fish and bird, possibly Christian or pagan symbols.

Highly abstracted forms derived from the classical tradition.

Zoomorphic: having elements of animal shapes

Function

Fibula: a pin or brooch used to fasten garments; showed the prestige of the wearer.

Small portable objects.

Context

Found in a grave.

Probably made for a woman.

Image

Hiberno Saxon Art

Hiberno Saxon art: The art of the British Isles in the Early Medieval period.

Hibernia: the ancient name for Ireland.

Hiberno Saxon art relies on complicated interlace patterns in a frenzy of horror vacui.

Horror vacui: (Latin, meaning “fear of empty spaces”) a type of artwork in which the entire surface is filled with objects, people, designs, and ornaments in a crowded, sometimes congested way

The borders of these pages harbor animals in stylized combat patterns, sometimes called the animal style.

Animal style: a medieval art form in which animals are depicted in a stylized and often complicated pattern, usually seen fighting with one another

Each section of the illustrated text opens with huge initials that are rich fields for ornamentation.

The Irish artists who worked on these books had exceptional handling of color and form, featuring a brilliant transference of polychrome techniques to manuscripts.

➼ Lindisfarne Gospels

Details

Early medieval Europe

c. 700

Made of illuminated manuscript, ink, pigments, and gold on vellum

Found in British Library, London

Gospels: the first four books of the New Testament that chronicle the life of Jesus Christ

Function

The first four books of the New Testament

Used for services and private devotion.

Materials: Manuscript made from 130 calfskins.

Content

Evangelist portraits come first, followed by a carpet page.

These pages are followed by the opening of the gospel with a large series of capital letters.

Context

Written by Eadrith, bishop of Lindisfarne.

Unusual in that it is the work of an individual artist and not a team of scribes.

Written in Latin with annotations in English between the lines; some Greek letters

Latin script is called half-uncial.

English added around 970; it is the oldest surviving manuscript of the Bible in English.

English script called Anglo-Saxon minuscule.

Uses Saint Jerome’s translation of the Bible, called the Vulgate.

Colophon at end of the book discusses the making of the manuscript.

Colophon: a commentary on the end panel of a Chinese scroll; an inscription at the end of a manuscript containing relevant information on its publication

Made and used at the Lindisfarne Priory on Holy Island, a major religious center that housed the remains of Saint Cuthbert.

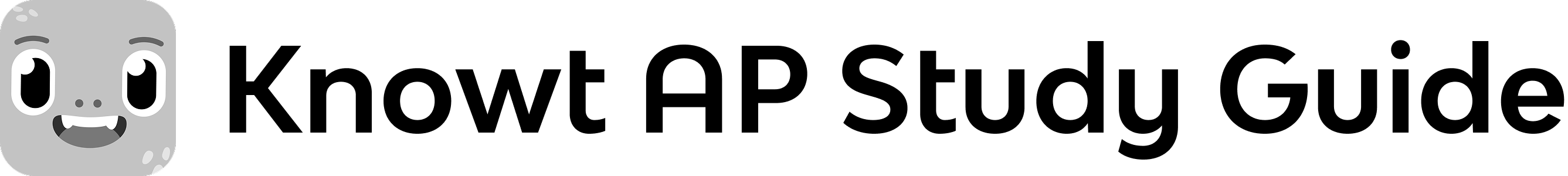

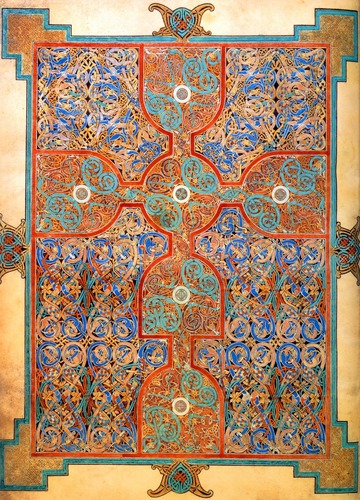

➼ Cross-carpet page

Details

From the Book of Matthew from The Book of Lindisfarne

c. 700

Made of illuminated manuscript, ink, pigments, and gold on vellum

Found in British Library, London

Form

Cross depicted on a page with horror vacui decoration.

Dog-headed snakes intermix with birds with long beaks.

Cloisonné style reflected in the bodies of the birds.

Elongated figures lost in a maze of S shapes.

Symmetrical arrangement.

Black background makes patterning stand out.

Context: Mixture of traditional Celtic imagery and Christian theology.

Image

➼ Saint Luke portrait page

Details

From The Book of Lindisfarne

c. 700

Made of illuminated manuscript, ink, pigments, and gold on vellum

Found in British Library, London

Context

The traditional symbol associated with Saint Luke is the calf (a sacrificial animal).

Identity of the calf is acknowledged in the Latin phrase “imago vituli.”

Saint Luke is identified by Greek words using Latin characters: “Hagios Lucas.” There is also Greek text.

Saint Luke is heavily bearded, which gives weight to his authority as an author, but he appears as a younger man.

Saint Luke sits with legs crossed holding a scroll and a writing instrument.

Influenced by classical author portraits.

Image

➼ Saint Luke incipit page

Details

From The Book of Lindisfarne

c. 700

Made of illuminated manuscript, ink, pigments, and gold on vellum

Found in British Library, London

Content

This page is called “Incipit,” meaning it depicts the opening words of Saint Luke’s gospel: “Quoniam Quidem…”

Numerous Celtic spiral ornaments are painted in the large Q; step patterns appear in the enlarged O.

Naturalistic detail of a cat in the lower right corner; it has eaten eight birds.

Incomplete manuscript page; some lettering not filled in.

Image

Chapter 10: Early Medieval Art

Key Notes

Time Period

Merovingian Art: 481–714 (from France)

Hiberno-Saxon Art: 6th–8th centuries (British Isles)

Culture, beliefs, and physical settings

Early Medieval art is a part of the medieval artistic tradition.

In the Early Medieval period, royal courts emphasized the study of theology, music, and writing.

Early Medieval art avoids naturalism and emphasizes stylistic variety.

Text is often incorporated into Early Medieval artworks.

Cultural interactions

There is an active exchange of artistic ideas throughout the Middle Ages.

There is a great influence of Roman art on Early Medieval art.

Audience, functions and patron

Works of art were often displayed in religious or court settings.

Surviving architecture is mostly religious.

Theories and Interpretations

The study of art history is shaped by changing analyses based on scholarship, theories, context, and written records.

Contextual information comes from written records that are religious or civic.

Historical Background

In the year 600, almost everything that was known was old.

The great technological breakthroughs of the Romans were either lost to history or beyond the capabilities of the migratory people of the seventh century.

This was the age of mass migrations sweeping across Europe, an age epitomized by the fifth-century king, Attila the Hun, whose hordes were famous for despoiling all before them.

The Vikings from Scandinavia, in their speedy boats, flew across the North Sea and invaded the British Isles and colonized parts of France.

Other groups, like the notorious Vandals, did much to destroy the remains of Roman civilization.

So desperate was this era that historians named it the “Dark Ages,” a term that more reflects our knowledge of the times than the times themselves.

However, stability in Europe was reached at the end of the eighth century when a group of Frankish kings, most notably Charlemagne, built an impressive empire whose capital was centered in Aachen, Germany.

Patronage and Artistic Life

Monasteries were the principal centers of learning in an age when even the emperor, Charlemagne, could read, but not write more than his name.

Artists who could both write and draw were particularly honored for the creation of manuscripts.

The concept that artists should be creative and communicate something new in each work was unknown in the Middle Ages.

Scribes copied the Bible and medical treatises, not modern literature or folk stories.

Scribes had to retain the original phrasing, while artists had to balance conventional and new methods.

Thus, a manuscript's text is usually an exact duplicate of a constantly recopied book, but the pictures offer the artist considerable latitude.

Early Medieval Art

One of the great glories of medieval art is the decoration of manuscript books, called codices, which were improvements over ancient scrolls both for ease of use and durability.

A codex was made of resilient antelope or calf hide, called vellum, or sheep or goat hide, called parchment.

These hides were more durable than the friable papyrus used in making ancient scrolls.

Hides were cut into sheets and soaked in lime in order to free them from oil and hair.

The skin was then dried and perhaps chalk was added to whiten the surface.

Artisans then prepared the skins by scraping them down to an even thickness with a sharp knife; each page had to be rubbed smooth to remove impurities.

The hides were then folded to form small booklets of eight pages.

The backbone of the hide was arranged so that the spine of the animal ran across the page horizontally.

This minimized movement when the hide dried and tried to return to the shape of the animal, perhaps causing the paint to flake.

Illuminations were painted mostly by monks or nuns who wrote in rooms called scriptoria, or writing places, that had no heat or light, to prevent fires.

Vows of silence were maintained to limit mistakes.

A team often worked on one book; scribes copied the text and illustrators drew capital letters as painters illustrated scenes from the Bible.

Scriptorium: a place in a monastery where monks wrote manuscripts

Manuscript books had a sacred quality.

The word of God; had to be treated with appropriate deference.

Covered with bindings of wood or leather, and gold leaf was lavished on the surfaces.

Precious gems were inset on the cover.

Objects are done in the cloisonné technique, with horror vacui designs featuring animal style decoration.

Interlace patternings are common.

Images enjoy an elaborate symmetry, with animals alternating with geometric designs.

Merovingian Art

Merovingians: A dynasty of Frankish kings who, according to tradition, descended from Merovech, chief of the Salian Franks.

Power was solidified under Clovis (reigned 481–511) who ruled what is today France and southwestern Germany.

The Frankish custom of dividing property among sons when a father died led to instability because Clovis’s four male descendants fought over their patrimony.

Royal burials supply almost all our knowledge of Merovingian art.

A wide range of metal objects were interred with the dead, including personal jewelry items like brooches, discs, pins, earrings, and bracelets.

Garment clasps, called fibulae, were particular specialties.

They were often inlaid with hard stones, like garnets, and were made using chasing and cloisonné techniques.

Chasing: to ornament metal by indenting into a surface with a hammer

Cloissonné: enamelwork in which colored areas are separated by thin bands of metal, usually gold or bronze

➼ Merovingian looped fibulae

Details

Early medieval Europe

Mid-6th century

Made of silver gilt worked in filigree with semiprecious stones, inlays of garnets and other stones

Found in Musee d’Archeologie Nationale, Saint-Germain-en-Laye, France

Form

Zoomorphic elements—fish and bird, possibly Christian or pagan symbols.

Highly abstracted forms derived from the classical tradition.

Zoomorphic: having elements of animal shapes

Function

Fibula: a pin or brooch used to fasten garments; showed the prestige of the wearer.

Small portable objects.

Context

Found in a grave.

Probably made for a woman.

Image

Hiberno Saxon Art

Hiberno Saxon art: The art of the British Isles in the Early Medieval period.

Hibernia: the ancient name for Ireland.

Hiberno Saxon art relies on complicated interlace patterns in a frenzy of horror vacui.

Horror vacui: (Latin, meaning “fear of empty spaces”) a type of artwork in which the entire surface is filled with objects, people, designs, and ornaments in a crowded, sometimes congested way

The borders of these pages harbor animals in stylized combat patterns, sometimes called the animal style.

Animal style: a medieval art form in which animals are depicted in a stylized and often complicated pattern, usually seen fighting with one another

Each section of the illustrated text opens with huge initials that are rich fields for ornamentation.

The Irish artists who worked on these books had exceptional handling of color and form, featuring a brilliant transference of polychrome techniques to manuscripts.

➼ Lindisfarne Gospels

Details

Early medieval Europe

c. 700

Made of illuminated manuscript, ink, pigments, and gold on vellum

Found in British Library, London

Gospels: the first four books of the New Testament that chronicle the life of Jesus Christ

Function

The first four books of the New Testament

Used for services and private devotion.

Materials: Manuscript made from 130 calfskins.

Content

Evangelist portraits come first, followed by a carpet page.

These pages are followed by the opening of the gospel with a large series of capital letters.

Context

Written by Eadrith, bishop of Lindisfarne.

Unusual in that it is the work of an individual artist and not a team of scribes.

Written in Latin with annotations in English between the lines; some Greek letters

Latin script is called half-uncial.

English added around 970; it is the oldest surviving manuscript of the Bible in English.

English script called Anglo-Saxon minuscule.

Uses Saint Jerome’s translation of the Bible, called the Vulgate.

Colophon at end of the book discusses the making of the manuscript.

Colophon: a commentary on the end panel of a Chinese scroll; an inscription at the end of a manuscript containing relevant information on its publication

Made and used at the Lindisfarne Priory on Holy Island, a major religious center that housed the remains of Saint Cuthbert.

➼ Cross-carpet page

Details

From the Book of Matthew from The Book of Lindisfarne

c. 700

Made of illuminated manuscript, ink, pigments, and gold on vellum

Found in British Library, London

Form

Cross depicted on a page with horror vacui decoration.

Dog-headed snakes intermix with birds with long beaks.

Cloisonné style reflected in the bodies of the birds.

Elongated figures lost in a maze of S shapes.

Symmetrical arrangement.

Black background makes patterning stand out.

Context: Mixture of traditional Celtic imagery and Christian theology.

Image

➼ Saint Luke portrait page

Details

From The Book of Lindisfarne

c. 700

Made of illuminated manuscript, ink, pigments, and gold on vellum

Found in British Library, London

Context

The traditional symbol associated with Saint Luke is the calf (a sacrificial animal).

Identity of the calf is acknowledged in the Latin phrase “imago vituli.”

Saint Luke is identified by Greek words using Latin characters: “Hagios Lucas.” There is also Greek text.

Saint Luke is heavily bearded, which gives weight to his authority as an author, but he appears as a younger man.

Saint Luke sits with legs crossed holding a scroll and a writing instrument.

Influenced by classical author portraits.

Image

➼ Saint Luke incipit page

Details

From The Book of Lindisfarne

c. 700

Made of illuminated manuscript, ink, pigments, and gold on vellum

Found in British Library, London

Content

This page is called “Incipit,” meaning it depicts the opening words of Saint Luke’s gospel: “Quoniam Quidem…”

Numerous Celtic spiral ornaments are painted in the large Q; step patterns appear in the enlarged O.

Naturalistic detail of a cat in the lower right corner; it has eaten eight birds.

Incomplete manuscript page; some lettering not filled in.

Image

Knowt

Knowt